The unfinished is, of course, something which tells us about the history of a work of art’s creation. A work of art may have been interrupted by the artist’s death, as with the paintings that Klimt left behind in his studio. Or it may simply have been abandoned when a patron failed to fulfil his obligations, or the painter had grown bored with the subject and moved on to something else. These spaces and gaps give us a glimpse of an artist at work and invite us to speculate about what Mondrian, for instance, was doing abandoning the 1934 ‘Composition with Double Lines’ or Cézanne the 1898 ‘Bouquet of Peonies’. Did something better come along? Did the painting present too many problems? The unfinished work puts us in the same room as an artist about to make his next decision, and invites us to wonder what got in the way.

But uncompleted works are not just pieces of biographical information. Since classical times, their appeal has been understood, and artists have had to accept that what they leave unfinished may be exposed to the public, and may even be more admired than their finished productions. Some may embrace this enthusiasm for the unfinished and produce works which encapsulate the effect, featuring blank spaces and unstarted areas that were never intended to be any different from their scrappy appearance. Indeed, it is often a real problem for art scholars to determine whether a painting by Manet, for instance, can be regarded as finished or not. Inspired flight may on occasions be cunningly contrived.

Pliny’s insight into unfinished works is still highly suggestive:

The last works of artists and their unfinished pictures… are more admired than those which they finished, because in them are seen the preliminary drawings left visible and the artists’ actual thoughts, and in the midst of approval’s beguilement we feel regret that the artist’s hand while engaged in the work was removed by death.

The glimpse of the artist’s working practices goes a very long way. The revelation of structural underdrawing, for instance, revealed in a Reynolds long suspected to be of Dr Johnson’s black servant Francis Barber, would be alluringly recreated in recent paintings by Euan Uglow, where the structural underpinning of a nude is made absolutely clear in finished works.

There are, too, questions of unusual — or unique — working practices which make us reconsider the artist’s other works. If most unfinished portraits reveal a classical practice that starts with the likeness and proceeds to fill out the setting, others can reveal a much more eccentric procedure. Gustav Klimt died suddenly, with a number of portraits still in the studio. It is startling to see from them that he was accustomed to paint the pudenda and pubic hair of his women sitters before covering them with his usual rich drapery. And the last, unfinished nudes of Lucian Freud reveal an engagement with sexual imagery that is unlike anyone else’s.

The imitation of unfinished or damaged works of art in completed productions is an old phenomenon. Michelangelo’s Slaves, agonizingly emerging from blocks of marble, the chisel marks preserved in different states, are pretty definitely intended to be like that. The age that told the story of him insulting his fellow sculptor Ammanati —‘Che bel marmo hai rovinato’ — was fascinated by his working practices, and would have loved works of art that revealed them for all time. In the 18th century, the cult of the ruin was reflected in paintings that revelled in the half-considered, the slapdash, the improvised and the utterly chaotic. Much of Fuseli only makes sense if you think of it as dashed off in the course of a long night, and hardly completed at all.

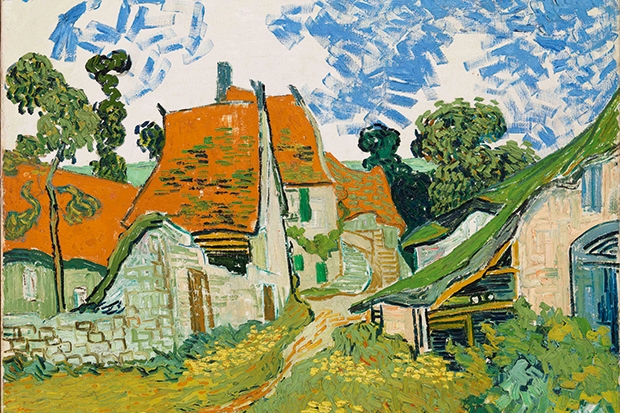

The unfinished, as an artistic category, contributed in important ways to one of the longest-running debates in painting: that between advocates of ‘finish’, like Ruskin, and those who revel in the painterly — the work of art that only reveals its subject at a distance. To look at Constable’s work, it is not at all easy to distinguish between the casually unfinished, the full-scale oil sketch or the completed painting. Taste changes over time: sometimes the small cloud sketches — or the huge six-foot sketches — are preferred to, say, his finished ‘Hadleigh Pier’. What we can say is that the unfinished work — as well as the plein-air sketch — contributed in important ways to the flourishing of the painterly, seen in the later 19th century in the Impressionists and in artists like the German Adolph Menzel.

This book is the catalogue of a fascinating exhibition in New York (The Metropolitan Museum of Art until 4 September). It is well worth buying for the sake of its scholarly insights, and I learnt a good deal from its essayists. Perhaps they would have done better to have left off before discussing the idea of the unfinished among conceptual artists, where it is too difficult to fake the incomplete (in many cases it’s impossible to say what a complete work of conceptual art would consist of). What really fascinates are the underdrawn figures, the alluring emergence of the canvas through primer at the corners, the thin spaces where you can see the painter thinking — or pretending to think.

Of course, the cult of the unfinished has gone a little too far. In other fields, too, it is surprising how things that were left merely suggested are often prized as much as works that were completed. There is a small industry of musicians finishing off the deathbed sketches of composers; some, such as Friedrich Cerha’s completion of Berg’s Lulu, where only a few gaps remained, are legitimate. Others, such as the various completions of Mahler’s tenth symphony, are expressions of what was clearly in large parts a half-considered first draft. Others still are free fantasies on themes found in sketchbooks (there is not much on which to base a realisation of Elgar’s third symphony, for example) or have to be written based on nothing at all, such as the last pages of Puccini’s Turandot.

Happily, the longstanding status of the unfinished work of visual art means that nobody has ever proposed doing the back half of Michelangelo’s Slaves. But another art form does suggest that we may find the promise of the unfinished too seductive. In my view, the incomplete novel or poem is regularly overvalued: Nabokov’s last novel was recently issued to a fanfare that none of his other late novels has ever commanded. Would The Faerie Queene be any greater if Spenser had got around to the remaining five-and-a-half books? Or is that all really just about enough?

As far as the visual arts go, the allure of painterly textures, of blank spaces, of the inspired pencil leaping forward and then abandoning itself in mid-structure, is undeniable. But there is something a little misguided about the regular preference for the unfinished — for the pot of paint flung in the public’s face — over the beautifully completed and polished. There is space for both. This interesting volume and exhibition give us plenty of room to ponder.

Comments