In a recent interview Oleksandr Syrskyi, the new commander-in-chief of the Ukrainian army, said that he spends his time off reading books on the country’s ‘difficult history’. If even he finds it difficult, where do us non-Ukrainians start?

In the introduction to its new exhibition, the Royal Academy makes a brave attempt at explaining the political background to Ukrainian modernism, developed in a brief window of creative opportunity before it was slammed shut by Soviet repression. To western eyes, though, it’s not immediately clear what distinguishes the 70 works on show – the majority on loan from Ukraine’s National Art Museum and Museum of Theatre, Music and Cinema – from the ‘Russian avant-garde’ with which they tend to get lumped, and from which the show deliberately sets out to separate them. It doesn’t help that the artists whose names are familiar to us – Kazymyr Malevych (Ukrainian spellings are favoured), Sonia Delaunay, Alexandra Exter and Alexander Archipenko – were either not Ukrainian by birth or made their names elsewhere, in most cases both.

The joyless shadow of socialist realism can already be glimpsed falling across 1920s Ukrainian art

Malevych, born in Kyiv to Polish parents, moved to Moscow in 1904, returning in 1928 to teach at Kyiv Art Institute after his brand of formalist abstraction was denounced in Russia. The others decamped to Paris. Delaunay, born to Jewish parents in Odesa, left for the French capital in 1905, followed by Exter, born to a Greek mother and a Belarusian father in what is now the Polish city of Bialystok, then part of the Russian empire, in 1907 and Archipenko, born to Ukrainian parents in Kyiv, in 1908. So far, so complicated – and it doesn’t get simpler.

Delaunay and Archipenko settled in France, where Delaunay became part of the school of Paris; it was Exter, returning to Kyiv in 1914, who gave form to Ukrainian modernism by grafting the cubo-futurism she had learned in Paris onto the root stock of Ukrainian folk art. The vibrantly coloured hybrid style she created – after spending some time designing sets and costumes for the Chamber Theatre in Moscow – found disciples in the private teaching studio she set up in Kyiv. Arriving in the city in time for New Year 1918, she found herself stranded by political events.

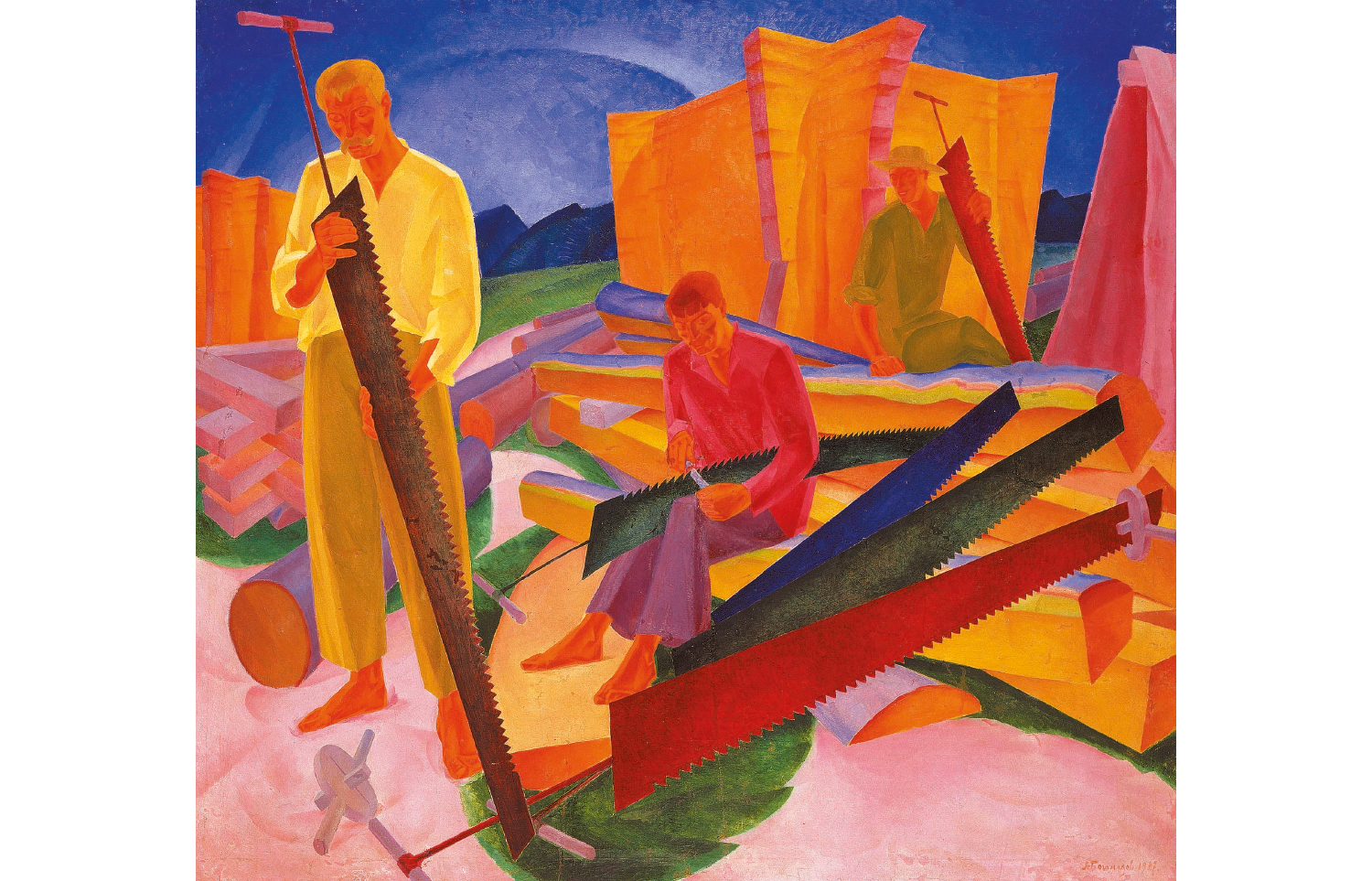

That was the year the newly proclaimed Ukrainian People’s Republic declared independence from Russia. It was short-lived. A protracted and bloody war with the Bolsheviks was followed by the establishment in 1922 of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, which initially adopted a cultural policy of ‘Ukrainisation’ as a sop to local feeling. It couldn’t last; by 1931, the Soviet authorities were imposing socialist realism on Ukraine’s newly liberated avant-garde. Its joyless shadow can already be glimpsed falling across the Ukrainian art of the late 1920s, with its proletarian subjects recalling Italian novecento painting, without the heart. Despite its saturated palette of colours, the light has gone out of Oleksandr Syrotenko’s ‘Rest’ (1927): the faces of his labourers, with their big idle hands, are dead-eyed and blank. In Oleksandr Bohomazov’s ‘Sharpening the Saws’ of the same year, the lackadaisical sawyers seem to be struggling to carve out a place in a Soviet world; from the expressions on their faces, they can think of better uses for their blades than promoting a Soviet proletarian idyll.

Shown at the 1930 Venice Biennale, ‘Sharpening the Saws’ was intended as part of a triptych left unfinished after the painter’s death from TB. Few of the artists in this show made old bones. Volodymyr Burliuk, painter of the pointillist-influenced ‘Ukrainian Peasant Woman’ (1910-11) – its dots look more like tapioca – died in 1917 as a conscript in the first world war, but most were casualties of the Stalinist purges of the 1930s. Mykhailo Boichuk, whose studio executed monumental murals for public buildings across Ukraine in the 1920s in a Byzantine revivalist style with an added pinch of European modernism, was accused of running a terrorist organisation and executed as a ‘bourgeois nationalist’ in the great purge of 1937. He and his fellow ‘Boichukists’ became part of a generation of martyrs remembered as the ‘Executed Renaissance’: a flowering of Ukrainian national culture nipped in the bud.

A rare survivor was Anatol Petrytskyi, the star of this show. As a painter, Petrytskyi did a fine line in social, rather than socialist, realism: his ‘Invalids’ (1924), a lament for the wounded in the first world war, was awarded a medal at the 1930 Venice Biennale, where it caused a sensation. For an artist whose name is hardly known in the West, Petrytskyi seems to have been strangely influential. His grungy ‘At the Table’ (1926), which features a woman dwarfed by a giant radiator, is a kitchen sink painting a generation before its time, while his portrait of the futurist poet ‘Mykhail Semenko’ (1929) seen through a café window is so similar in style to the later work of the Italian communist Renato Guttuso that you’d swear he was familiar with the Ukrianian’s paintings. Perhaps he was. Semenko’s portrait was one of more than a hundred Petrytskyi made of his contemporaries, only 20 of which have survived as memorials to a decimated intelligentsia. Semenko himself became part of the ‘Executed Renaissance’.

The artist’s costume designs have fortunately fared better. Exter was an influence here too: the young Petrytskyi attended a stage design course in her Kyiv studio, before discovering constructivism in Moscow. His jauntily diagrammatic figures formed of geometric shapes exude a youthful creative energy reminiscent of the early etchings of David Hockney, who seems to put in a mysterious cameo appearance as the figure in the flat cap and round glasses in a design for Eccentric Dances at the Moscow Chamber Ballet in 1922. Beside the inventiveness of Petrytskyi’s 1928 costume designs for Turandot at the State Opera Theatre, Kharkiv – the relative stature of the male protagonists is measured in the height of their stacks of hats – the original designs for the La Scala premiere of two years earlier look boringly conventional. For drawings meant to serve just as illustrations, Petrytskyi’s are ingeniously crafted: his Turandot costumes incorporate collage, while in a 1925 design for Mussorgsky’s The Fair at Sorochyntsi at the State Opera Theatre, Kharkiv, the hero wears an astrakhan hat mocked up from collaged barley seeds and a woollen overcoat roughly textured with sand.

The designs by Petrytskyi’s contemporaries Oleksandr Khvostenko-Khvostov and Vadym Meller (see above) – also students of Exter before she left Kyiv for Moscow and eventually Paris to teach design at Léger’s Académie Moderne – are just as delightful. In the work of this constellation of theatrical talent one catches a glimpse of something distinctively Ukrainian – a visual wit – that seems to be missing from the paintings in this exhibition, caught between European dominance and Russian repression.

In the Eye of the Storm: Modernism in Ukraine, 1900-1930s is at the Royal Academy of Arts until 13 October.

Comments