When Winston Churchill dined with the crème de la crème of American finance in New York on 28 October 1929, a facetious toast was made to ‘friends and former millionaires’. Despite a 13 per cent drop in the Dow after another day of market turmoil, the assembled banking titans felt they wouldn’t just survive the maelstrom, they would make more money from it. Churchill, whose finances were perennially chaotic, had caught stock market fever and lost today’s equivalent of almost $1.5 million. On returning to England, he declared the Wall Street crash ‘only a passing episode in the march of a valiant and serviceable people’.

In the end, US stocks fell almost 90 per cent between their 1929 peak and 1932. The crash had catastrophic consequences for those drawn into the market by apparently easy profits and set the scene for the Great Depression. Economic optimism was snuffed out, bank failures exploded, foreign trade collapsed and unemployment soared.

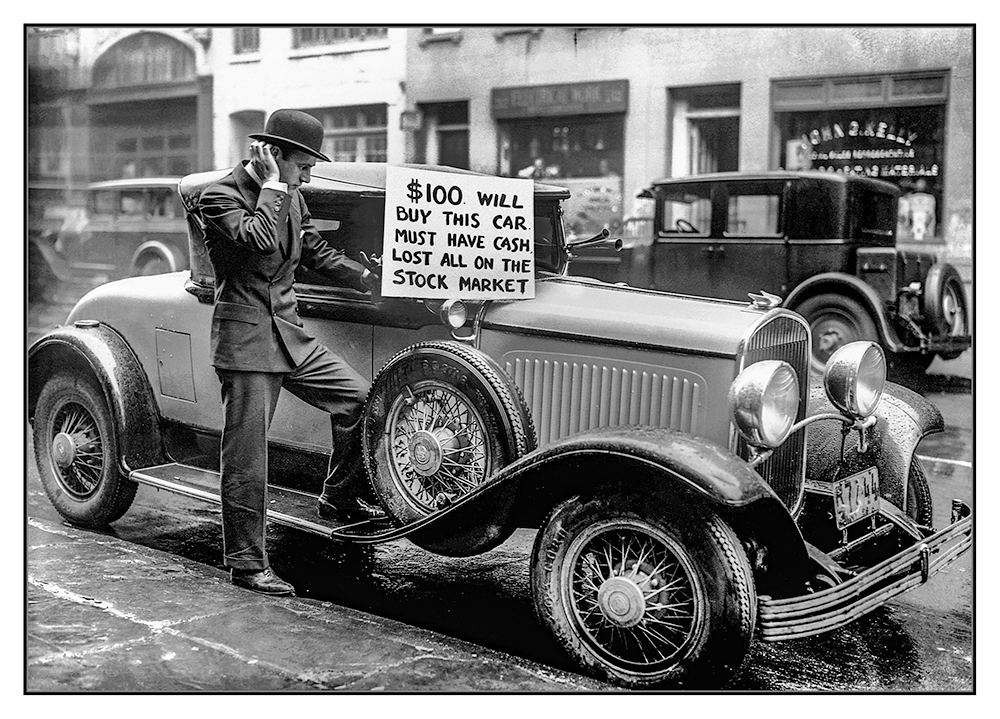

Almost a century on, the crash remains the father of financial catastrophes in the popular imagination. While the intricacies may be poorly understood, the eerie photographs of paralysed crowds outside the New York Stock Exchange and stories of stockbrokers throwing themselves out of windows mean the period continues to fascinate.

The crash and its aftermath have some obvious parallels and connections with our own era. The post-crash battle between Wall Street and Washington echoes the modern blame game that erupted after the financial crisis of 2007-08. The Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930, which raised tariffs to almost 60 per cent in a bid to protect American farmers, provide legal support for the current administration’s levies in the view of Scott Bessent, the treasury secretary.

In policy terms, a big question is whether the Federal Reserve made the right moves with its action (or inaction) on interest rates and out-of-control margin lending. Then there was the largely ineffectual President Herbert Hoover, advised by the treasury secretary Andrew Mellon to let the burning US economy ‘liquidate labour, liquidate stocks, liquidate the farmers, liquidate real estate’.

While only a fraction of Americans were investors, a speculative mindset had infected the culture in the bright new world of the mass consumer economy. This led to what the Harvard economist John Kenneth Galbraith described as a ‘great speculative orgy’. Another phrase that comes to mind is the Scottish journalist Charles Mackay’s ‘madness of crowds’. Bernard Baruch, the speculator who hosted the New York soirée for Churchill, sold his stocks after reading Mackay’s 1841 Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.

Andrew Ross Sorkin’s 1929 is peppered with superb episodes that highlight how those across the social spectrum were carried away into ‘collective delusion’. One senior banker was forced to leave lunch to advise his ‘angry and agitated’ servants on their mounting financial losses. Evangeline Adams, a popular astrologist who made stock recommendations based on zodiac signs, instructed her broker to sell it all after being told she had lost $100,000.

Bankers presented a facade of gentlemanly finance, but this was a world of dubious insider trading

Given how much time has passed, Sorkin’s promise of an ‘inside story’ could have disappointed. But he successfully takes us into the lives and minds of key figures through an effective and engaging narrative approach and the help of some fresh sources, chiefly the Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s board minutes, and unpublished memoirs.

Thefocus is on the personalities at the top of Wall Street, those with the most to lose – and gain – from the frenzied market. His cast includes such intriguing and complicated characters as the National City Bank’s Charles Mitchell (who ended up on trial for tax fraud); the trader Jesse Livingston (who committed suicide at the Sherry-Netherland hotel); John Jakob Raskob (the creator of the Empire State Building); and the prosecutor Ferdinand Pecora (the ‘Hellhound of Wall Street’).

The crash was intrinsically political, so we also get Hoover’s uncertain reaction to events and the (now mythologised) rise of Franklin D. Roosevelt as the US headed towards the New Deal. Particularly interesting is Sorkin’s exposition of the battle between Mitchell and the Virginia Senator Carter Glass, who viewed the banker as Wall Street’s ‘chief offender’.

While bankers presented a facade of gentlemanly finance, this was a world of dubious insider trading and fixed markets, as Sorkin shows. The tools used to fool ordinary investors included investment pools, where insider manipulation ‘could move the stock up at will’. With such deceptive methods ‘it was just a question of how much they could get away with’. But, given the lessons of subsequent major crashes, Sorkin’s assessment seems justified – that, except for the fraudulent stock exchange president Richard Whitney, ‘it’s hard to make the case that any of the era’s other major financial figures did anything appreciably worse than most individuals would have done in their positions and circumstances’.

1929 is a highly readable account of a market crash that continues to fascinate. While an unsurprising conclusion in favour of humility and the lesson that ‘we need to remember how easily we forget’ does leave the reader wanting a deeper final analysis, Sorkin has brought to life a very human tale of greed and desperation and produced a worthy companion to the great works on the subject.

Comments