Even if you don’t like Christmas, it’s hard to deny that Christmas dinner is one of the best meals of the year. But for Parisians in 1870, the Christmas meal took an unexpected and macabre turn.

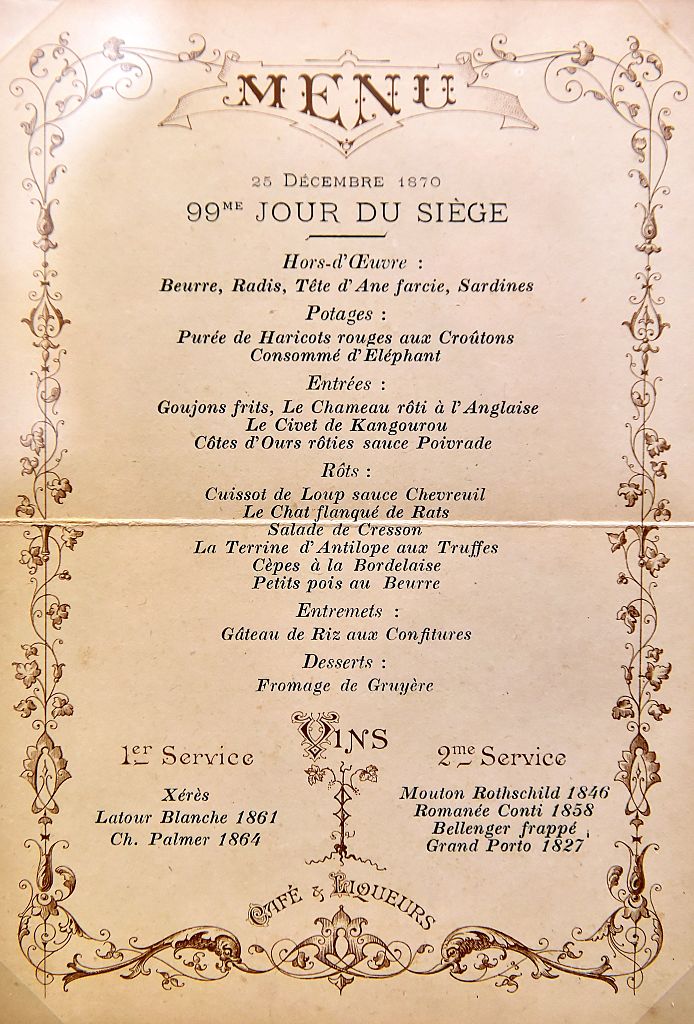

While we may think of Paris as being the city of light, good food and fine wine, it’s also the city that once produced a Christmas Day menu of stuffed donkey head, elephant consommé and roasted camel – all courtesy of the Jardin des Plantes zoo.

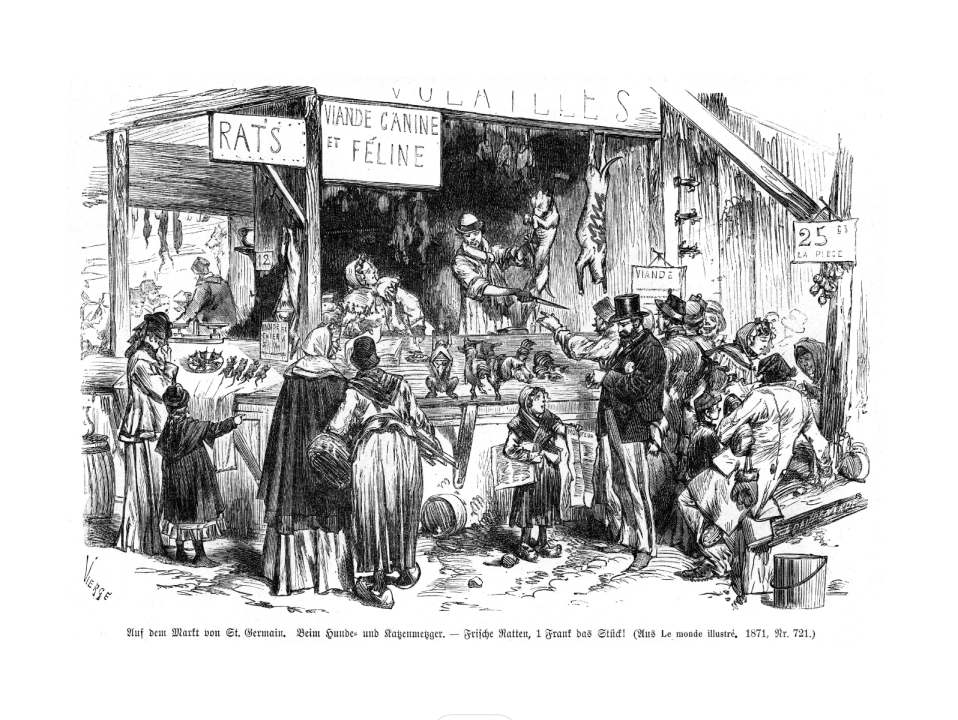

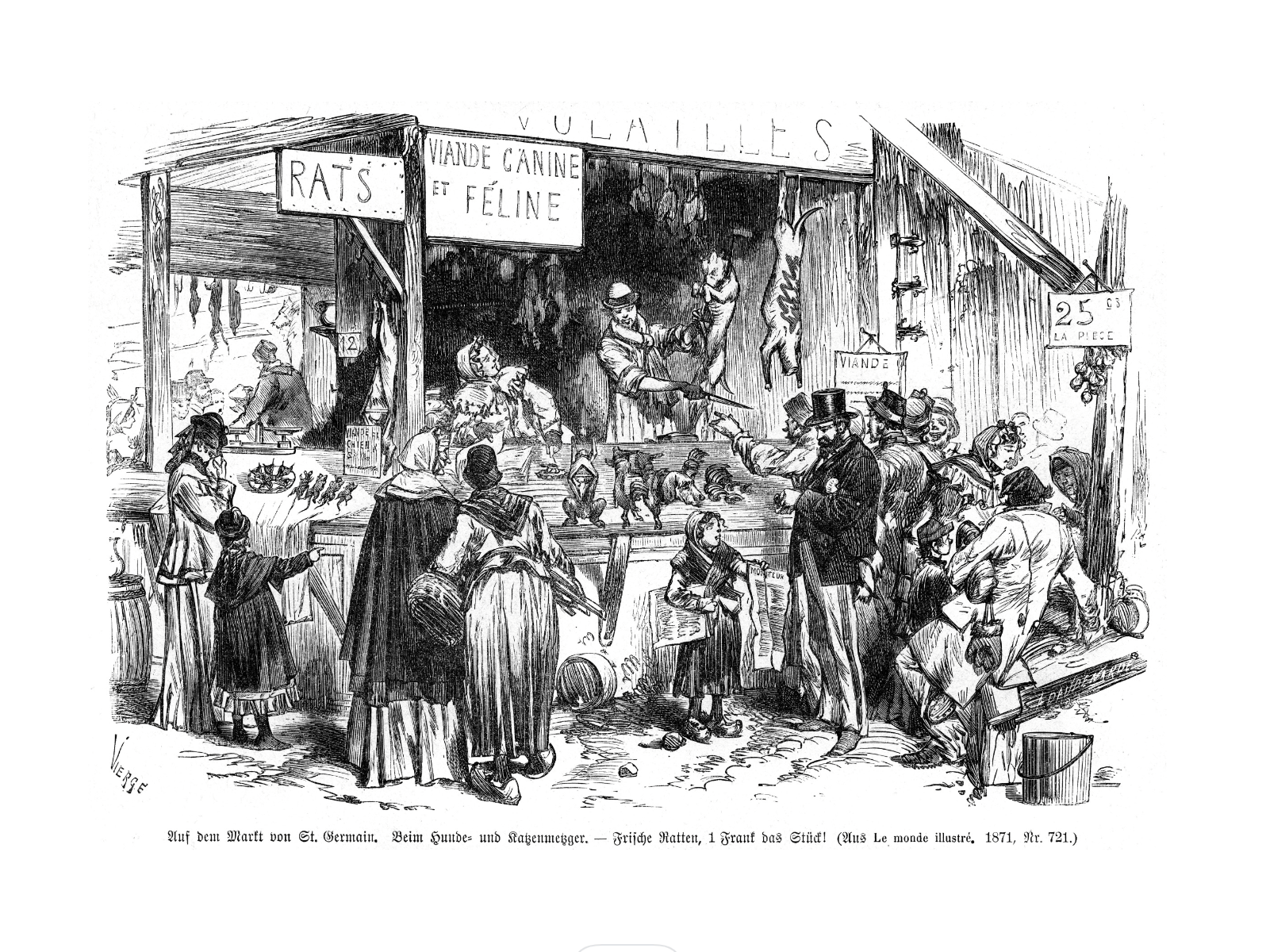

In the late stages of the Franco-Prussian war, Paris found itself surrounded by enemy forces. The Germans aligned themselves with Prussia with a plan to bombard and starve Parisians into submission. All supplies to the city were cut off, meaning there was no meat, fresh vegetables, butter, milk or cheese to be found. But the residents of Paris still needed to eat – and they started to look towards cats, dogs, horses and eventually rats to keep themselves nourished.

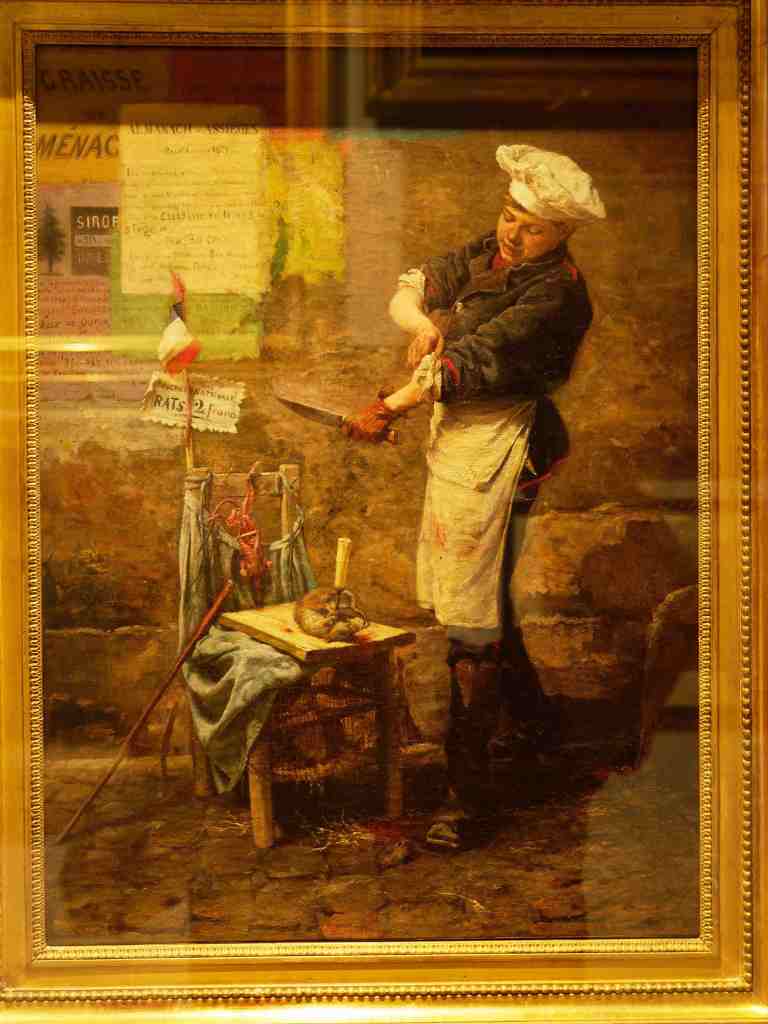

Butchers began popping up selling dog, cat and rat meat to the masses. A painting by Narcisse Chaillou depicts a young boy who set up as a butcher selling rats on the Parisian streets:

And Chaillou wasn’t the only artist who documented the fare of the time. In a letter to his wife, painter Édouard Manet wrote: ‘There are cat, dog and rat butchers in Paris now, we eat nothing but horse when we can get it at all.’ It’s estimated that around 70,000 horses were killed for meat between September 1870 and January 1971, including two of Napoleon III’s stallions.

But even against a background of bombardment and famine, the elite still had an appetite for haute cuisine, and there was only one man for the job: chef Alexandre Etienne Choron.

Choron, best known outside Paris for his creation of the Choron sauce – a Béarnaise sauce without tarragon or parsley but a big dollop of tomato paste for colour and flavour – was head chef at one of the city’s most popular restaurants, Voisin. On Rue Saint Honoré, Voison was an establishment where prominent Parisians went to see and be seen – and Choron knew he couldn’t possibly serve his guests rat for Christmas dinner. So with limited options left, he had the wild idea to raid the local zoo.

‘It was tough, coarse, and oily, and I do not recommend English families to eat elephant as long as they can get beef or mutton’

Before the 1870 siege of Paris began, Jardin des Plantes zoo had been hugely popular among families, hosting a wide range of exotic animals including kangaroos, bears, tigers, camels, hippopotamuses and zebras. While some animals were killed during the bombardments, the fate of the survivors boiled down to how edible they appeared.

Among the most popular animals in the zoo were two elephants, Castor and Pollux. The pair, named after the twin sons of Zeus, had been used to giving rides on their backs around the zoo to families. But when the elite became hungry, their fondness for the elephants was quickly forgotten, and Castor and Pollux were soon to become dishes on one of the most historic menus of all time.

M. Deboos of the Boucherie Anglaise bought the elephants for 27,000 francs – a deal he did very well out of as he went on to sell cuts of their meat for ten to 14 francs per pound. The trunks, which were considered a delicacy, made 40-45 franks per pound. To put that into perspective, rats were being sold dead for 60 centimes or alive for 1 franc.

On Christmas Day 1870, the 99th day of the siege, Chef Choron opened the doors of Voisin and served a six-course menu to his upper-class clientele that included appetisers of stuffed donkey head and sardines, followed by a pureed red bean soup made with elephant stock. The main course was roasted camel, English-style kangaroo stew and bear chops roasted with a pepper sauce. Among the day’s roasts were haunch of wolf, cat flanked with rats and an antelope terrine with truffles, while those who didn’t fancy eating the zoo could dine on Bordeaux-style porcini mushrooms with buttered green peas. The feast was paired with fine wines, including Mouton Rothschild 1846, Château Palmer 1864 and Romanée-Conti 1858, all finished off with a very uninspired rice pudding and gruyere cheeseboard.

Of course, the elephant didn’t go down well with all the guests. Henry Labouchère, an English writer and politician who was in Paris at the time, recorded: ‘Yesterday, I had a slice of Pollux for dinner. Pollux and his brother Castor are two elephants, which have been killed. It was tough, coarse, and oily, and I do not recommend English families to eat elephant as long as they can get beef or mutton.’

Voisin wasn’t the only fine dining establishment to serve up animals from the zoo. Restaurant Peters, situated in a nice little spot near Paris opera house, offered a New Year’s Day feast of roast donkey, fillet of elephant in a Madère sauce, bear thighs and peacock.

A small selection of the zoo’s animals escaped the butcher’s block. Lions and tigers were off the menu, presumably because the butchers didn’t fancy becoming dinner themselves, monkeys because they had too much of a resemblance to humans and the hippopotamuses because they were deemed too unsanitary to eat.

Chef Choron continued selling elephant trunk with brown sauce and elephant meat cooked in red wine until he ran out in January 1871. Just a few days later, the Prussians breached Paris, resulting in more than 400 casualties, and the war finally ended – no doubt leaving the few animals remaining in Paris breathing a sigh of relief.

Comments