James Forsyth reviews the week in politics

MPs have a new favourite game: Hung Parliament. To solve this communal Rubik’s Cube you have to work out how a coalition could be put together if no party wins an overall majority — and what concessions would have to be made. But the real fun comes when you start working out which party leaders would have to be sacrificed to make any deal work. One scenario even ends up with leadership challenges in all three main parties — so with multidimensional fear, loathing and civil war.

Those MPs who will leave at the next election — just over half, when you count retirement and likely defeat — are taking special pleasure in forecasting chaos. The Lib Dems, runs the argument, would not do a deal with Labour if Gordon Brown were still leader — so he would finally have to go. David Cameron would face some kind of challenge if he did not secure an overall majority because his party would be so furious that they had lost an election that they should have won. While if Nick Clegg made any arrangement with either Labour or the Tories, his own party could be expected to revolt.

MPs who are staying are looking forward to the return of power to parliament. In the Blair years, parliament mattered little. Downing Street was where the action was. But in a hung parliament, every vote is on a knife-edge: every disgruntled MP suddenly counts. It would shift the locus of power from Whitehall and Downing Street back to the tea rooms, corridors and cloakrooms of the Commons. Party leaders and their aides would have to wait on backbench MPs rather than the other way round.

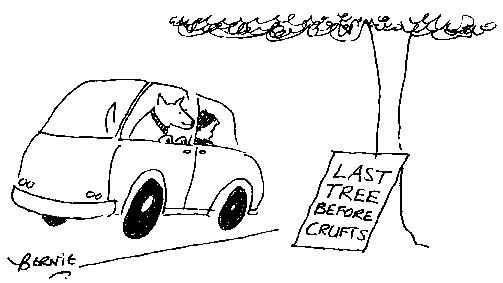

Tories, in particular, are fantasising about this last point. The infantry have started to compete with each other on their snub stories. One candidate for a marginal seat recently drove Mr Cameron around his constituency all day on a recent trip, and was shocked that when he dropped Mr Cameron off, the Tory leader got out of the car without so much as a word of thanks. Some MPs are planning to take elaborate revenge on Mr Cameron if he ends up being reliant on their vote.

The faction-counting has had one major effect: MPs have been reminded about the extent to which their own parties are coalitions. Labour MPs, in particular, are being reminded that some dividing lines cut across party boundaries. An example of this is that a pamphlet published this week, ‘After the Crash — reinventing the left in Britain’, contains essays from Labour, Lib Dem, Green and nationalist politicians as they attempt to thrash out a left-wing response to the country’s current predicament.

The Lib Dem MP who has contributed to this work is Steve Webb. Remember that name. If there is a hung parliament, Webb will, believe it or not, become a key political player. He is on the left of the Liberal Democrats, served on the Social Justice Commission with David Miliband in the 1990s and is now the figure that many in the Labour party are relying on to prevent any Lib-Con coalition.

Webb has, to put it politely, a strained relationship with his party leader. A while back Nick Clegg was overheard by a journalist saying on a plane, ‘Webb must go… He’s a problem. I can’t stand the man. We need a new spokesman. We have to move him. We need someone with good ideas.’ Webb has already had a modicum of revenge, heavily criticising the leadership at the last Lib Dem conference (this being the Lib Dems he has been able to do this while remaining a frontbench spokesman). But this is nothing compared to the trouble he could cause if Clegg made any deal with the Tories.

Any formal arrangement Clegg reached with Cameron would have to be ratified by the entire Lib Dem party membership. Webb’s organisational skills mean that he would almost certainly be able to defeat the leadership on this point — raising the prospect of a second election. Intriguingly, the Social Liberal Forum, the left-wing arm of the Lib Dems and a group whose advisory board Webb chairs, will turn itself into a mass membership organisation at Lib Dem spring conference this weekend. This provides a mechanism to mobilise opposition to any Clegg-Cameron agreement.

On the Labour side, the Lib Dem question reveals an interesting split between pluralists and tribalists. The Blairites have always been keen on a link with the Lib Dems because the Lib Dems’ liberal instincts would act as a check on Labour’s centralising, statist, Fabian tradition. Soon after Tony Blair was elected Labour leader, he explained to Andrew Adonis, now Transport Secretary, what he intended to do to the Labour party. Adonis, a former Lib Dem, replied jokingly that he should change the party’s name not to New Labour but to the Liberal Democrats.

The thinking left of the Labour party, the group around Jon Cruddas, are also in favour of adding a dab of yellow to their red politics. Again, this is driven by a desire to move away from the statist politics of the Fabians. But the Labour tribalists, a group who will back Ed Balls for leader when the time comes, reject this idea. They remain wedded to the clunking fist of the state and their idea of a coalition is a stitch-up between the Labour party machine and the trade union fixers.

If a defeated Labour party does not elect Balls leader (thereby demonstrating some survival instinct) then expect Labour to try to work with the Lib Dems on developing shared positions on Europe, the constitution and social justice.

By contrast, there is no wing of the Tory party that is enthusiastic about co-operating with the Lib Dems. The Tories might want to peel off individual Lib Dem MPs — George Osborne has made repeated passes at their schools spokesman, David Laws — but they don’t want to try to govern with them. In the event of a hung parliament, the Tories will produce a budget and dare the Lib Dems to vote it down.

Some older heads, including Lord Mandelson, think that there will not be a hung parliament. Certainly, in recent elections, the undecideds have tended to break strongly one way or the other. As one shadow Cabinet member puts it: when the government changes, ‘the British tend to swing behind the winning party significantly but at the last moment. They’ll do so again.’ Mr Cameron has about seven weeks to inspire such a swing, while people within and without his party carry on fiddling. If he can’t summon up this swing, it won’t be Nick Clegg who is the kingmaker but the oft-derided ‘sandal-wearing, lentil-eating’ membership of the Liberal Democrats. Then, no one will be able to solve the Rubik’s Cube.

Comments