Numerous research academics have contributed to this highly cogent show celebrating the craftspeople of Ancient Egypt. My pre-teen companion, though a big fan of Egypt, was still slightly hesitant about whether this would be the most interesting angle. It began with a 4,000-year-old stele, or tombstone, on loan from the Louvre, praising the sculptural and painterly skills of an artisan called Irtysen, about whom, of course, nothing more is known. The perennial problem.

General information, however, came thick and fast. We learned that a cooperative of skilled workers was a hemut, and a singular skilled worker a hemu. We came face-to-face with a cubit (a measuring stick six palms in length), a plumb line, several levelling rods, and the by-products of a crank drill (round cores of stone). We studied wall-paintings showing workers sitting, according to their superiority, either on stools or mud benches. We inspected several lumpy, unfinished works of sculpture emerging from a sketched grid system, as well as designs using the same grid system, proving that everyone was chiselling from the same hymnsheet, so to speak.

Art was inseparably bound up with religion and the state – with architecture, ritual and inscription. And yet the show (gently) challenged the cliché that Ancient Egyptian iconography was stiflingly standardised. It held up examples of artisans taking the initiative in embracing geological features in the rock they were carving, or showing ingenuity in other subtle ways. There were some incredible 5,000-year-old clay pots painted with wavy lines to imitate the more expensive originals made of stone, or painted with a criss-cross pattern, as if they had been slung in a woven net (the first skeuomorphs?). There was a cheeky unwonted signature carved in hieratic writing; and, waving to us across time, a handprint on the underside of a rough clay shrine.

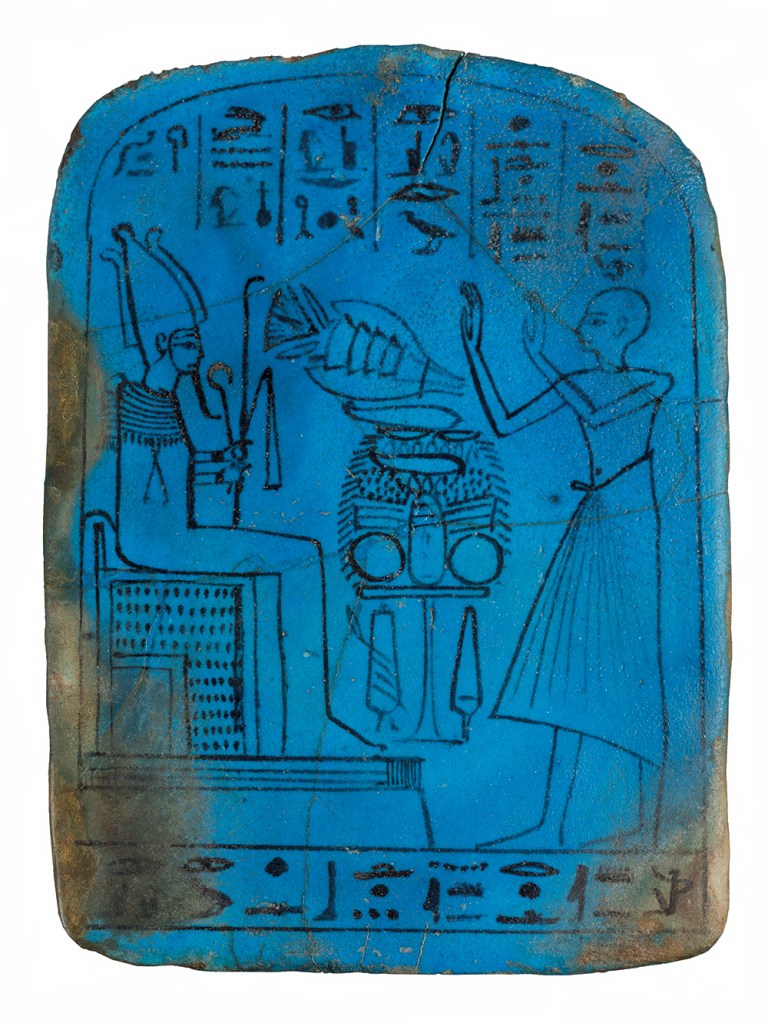

The artist Rekhamun made himself a memorial entirely out of faience (see below). Spectacularly blue – he describes himself as a ‘maker of lapis lazuli’ – it showed him meeting Osiris. There was something touchingly direct about self-penned memorials, though few would want the practice revived.

A little painted statue brings us face-to-face with chief weaver, Teti-ty, who probably oversaw a team of women weavers. Intended for his tomb, the smiling statuette makes him look like a nice bloke. Jewellers’ work is represented by tiny cloisonné flies and gold enamelled frogs; glasswork includes a 3,000-year-old flask shaped like a black bunch of grapes – a design classic. We learned that Egyptians called glass ‘the stone of the type that flows’ – suggesting they knew not just that it was malleable in heated form, but also that it continues to move and flow over centuries, much like their own exceptionally continuous civilisation.

As we walked into the textile room, a light was activated, indicating we were in the presence of sensitive treasure: there before us lay the 3,210-year-old sash of Rameses III. This made my companion gasp. She told me that Rameses III was assassinated by a concubine who wanted her son to inherit. The plotters were caught and executed but not before Rameses’s neck was slit to the very backbone by a knife. We wondered if the dark mottling on the sash could possibly be the spilled blood of Rameses III.

There before us lay the 3,210-year-old sash of Rameses III. This made my companion gasp

We checked the signage. ‘The weaver who made it was clearly highly skilled (a hemu) using 1,689 vertical yarns in a double-weave, with 360 yarns for the plain central section… Experiments suggest it would have taken three to four months to weave.’ The exhibition has possibly taken its academic remit a little too far in counting the threads but not mentioning the royal drama. Certainly, the craftsmanship on the sash is very fine. We tiptoed away and the light went off.

The catalogue contains an essay by Alessio delli Castelli and Dimitri Laboury providing an art-historical context. Archaeology indicates the sculptor Thutmosis ran a studio in Amarna, which they liken to the studios of Raphael or Rubens. Thutmosis is thought to have created not only Nefertiti’s famous head but also, possibly, the haunting, misshapen head of a princess, on loan here from Berlin, which forms the exhibition’s main image. Thutmosis, who lived during the reign of the individualist Akhenaten, has a glimmer of the modern artist.

But by and large, the makers’ lives were physically hard, repetitive and often dangerous. Orpiment would poison, while bronze required 1,000˚C heat. It is all there in the Teachings of Khety, which we discovered through the exhibition and read in full later. This was a popular text for junior scribes – more than 250 manuscript copies survive – and it sets out the benefits of being a scribe over all other professions, which are each denigrated in turn. ‘Vile is the carpenter’; ‘The jewel-worker… sits down to his food with his knees and back still bent’; ‘The mat-maker within the weaving shop/ Is worse off than a woman’ etc. It is surely the first white-collar piece of side-eye ever written; a foundational text for the middle classes. ‘Set your heart to writings!’ it exhorts. ‘Observe how it rescues from labour!’

It is ironic that this show, which wants so much to commend the makers of Ancient Egypt, ends up using Khety’s scornful and condescending treatise. Still, we left buzzing with ideas and inspiration.

Comments