I met Anthony by the gates of Thameside prison in south-east London. A skinny, gaunt-looking man in his 40s, he’d spent much of his adult life in and out of jail for offences linked to his mental health problems and addiction to drugs. His latest spell inside had lasted eight months. He was hugely relieved to be out and vowed, like so many other newly-released prisoners, never to go back.

Seventy-five per cent of probation staff are women but 91 per cent of those they supervise are male

Over the next few hours I joined Anthony and a support worker from a charity on a car journey across London as they raced against the clock to find him a bed for the night, register with a GP, so he could get the medication he needed, visit a benefits office and attend a probation appointment. It was a crazy few hours – complicated by the fact that Anthony’s identification documents were stuck in another prison and there’d been little time to organise things in advance of his release.

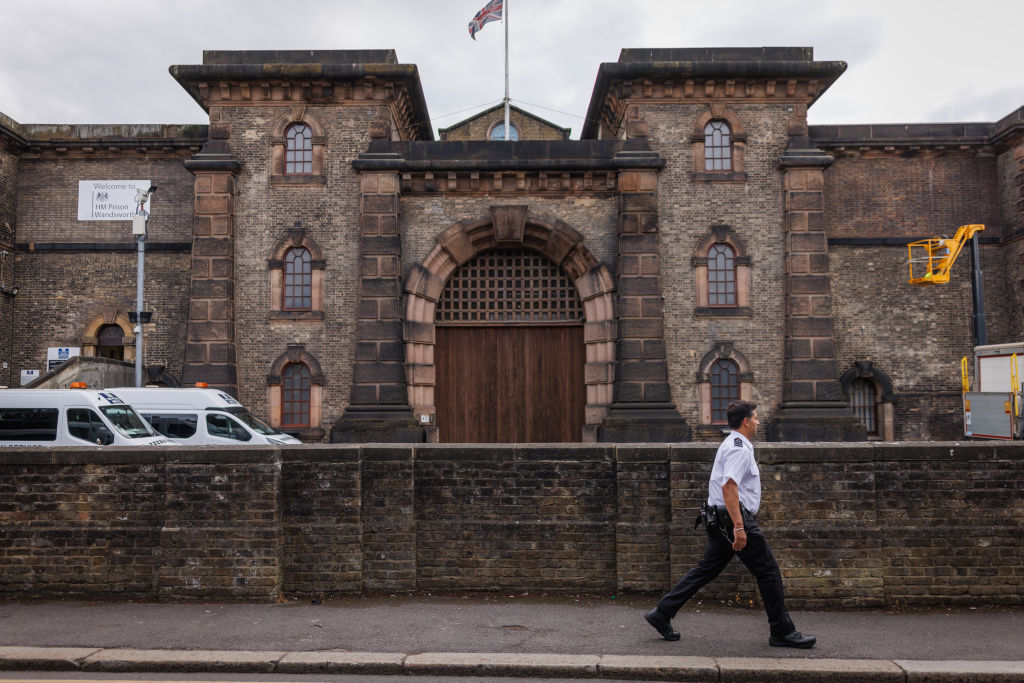

That encounter with Anthony, for a radio feature a few years ago, came to mind as the government prepares to free some 2,000 prisoners on Tuesday – double the number they usually let out in a week. It’s the first stage of a scheme which will see 5,000 prisoners let out early in September and October to create space in jails across England and Wales, where the population has reached a record high of 88,521. Inmates will serve 40 per cent of their sentence in custody instead of the standard 50 per cent.

However much planning has taken place, many of those released will face the same mad dash as Anthony did to access the services that will help them re-settle in the community. Key to it all will be the probation staff charged with their supervision. Since 2015, every offender, no matter how short their sentence, must be monitored by probation for at least 12 months after they leave jail. It’s a huge burden on a service which is overstretched and under-performing.

Only two out of 12 probation regions are operating satisfactorily, according to the latest ‘scorecard’ from the Ministry of Justice (MoJ). Three areas – East Midlands; London; Kent, Surrey and Sussex – are rated ‘inadequate’, seven are said to require improvement. In his final report after four years as chief inspector of probation, Justin Russell said his ‘greatest’ concerns were around public protection with staff unable to accurately assess and robustly manage the potential risk of serious harm posed by some offenders. Russell highlighted poor supervision and unmanageable workloads, with some officers dealing with 40 or more cases each.

A large part of the problem is that there aren’t enough staff. The MoJ wants there to be 7,339 fully-qualified probation officers, yet there’s currently a shortfall of 2,179. Leaving rates are up and most alarmingly, every year up to 20 per cent of trainees drop out before they even qualify.

To address the staffing crisis Martin Jones, the new chief inspector, has suggested reducing the burden on existing probation officers by removing the requirement to supervise prisoners who’ve served short sentences. It would cut the caseload by around 40,000, 17 per cent of the current total, and give staff more time to do meaningful rehabilitation work with offenders who pose a greater public threat. It’s an attractive idea but politically deadly: an unsupervised prisoner will inevitably commit a ghastly crime and ministers will get the blame.

A better option would be to tackle the bureaucracy surrounding probation work so staff have more one-on-one time with offenders. Russell highlighted Civil Service rules that meant it could take weeks to order equipment and fill posts. ‘Multiple layers of approvals and standardised and centralised commissioning processes stifle innovation and can feel disempowering for local leaders,’ he wrote. Officers also complain about legislative demands and data management requirements that they have to fulfil but which aren’t part of their core duties, as well as clunky IT systems that make every task take longer. If workloads are to be made manageable, this is an area the MoJ must urgently focus on.

The department appears to be pinning its hopes on a campaign to hire an extra 1,000 trainee probation officers. That will undoubtedly ease some of the pressures, but it would be a mistake to think that simply boosting numbers will improve performance. A theme of recent reviews into murders committed by offenders on probation is a lack of ‘professional curiosity’ on the part of officers entrusted with their supervision – they’re too willing to accept what they’re told at face value and don’t inquire deeply enough into what’s going on in the background. Much of this is down to inexperience: one-third of probation staff have been in the service for less than five years. A recruitment drive is unlikely to address that problem unless it’s targeted at older people who can bring skills from different walks of life.

Indeed, that was the recommendation from a report carried out for the Conservative government which said the probation service needed to hire more ‘career changers’ in their 30s, 40s and 50s. The findings of the review, which wasn’t published, also called for the service to bring in more men. Seventy-five per cent of probation staff are women but 91 per cent of those they supervise are male. The chief probation officer, Kim Thornden-Edwards, has agreed that the gender mix needs to change to give senior staff more options when allocating cases. ‘It might be really good for a woman to be leading on a domestic abuse case – but also, it might be good for a man to be challenging those kind of issues around masculinity and power from a male perspective,’ she told the BBC.

Thornden-Edwards made those remarks 18 months ago, but the gender balance in probation hasn’t shifted. If the service is to be more effective at keeping the public safe and helping offenders with rehabilitation the workforce needs to be more diverse, particularly in terms of age, life experience and gender. That is not to denigrate those who currently work there, they are doing a valuable and challenging job. But we should acknowledge that they need more support so that former prisoners like Anthony and the thousands exiting jail this week get the best chance to turn their lives around.

Watch more on SpectatorTV:

Comments