The first thing you notice is the frumpy tweed overcoat. Realistic bobbling. Fussy check. Bit pedantic, bit GCSE. Then the smooth, dull face. Enough wrinkles, modelling, to define age, but not really enough to examine character with any realism. She’s hard to read. It’s not the face of someone happy to be here. It’s more the face of someone enduring small talk. Maybe she’s being mansplained to?

The unveiling of Gillian Wearing’s statue to suffragist Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square is no doubt a cause for celebration. For if the suffrage movement was about anything it was about the right of iffy female artists to be allowed to make mediocre, stiff bronzes and to receive just as much blind acclaim as iffy male ones.

Wearing’s commitment to equality is deep – aesthetic as well as political. Her work reaches out to its neighbours in aesthetic kinship. It’s admirable how consistent, how in keeping with the sculpturally incompetent surroundings – the Fat Controller Lloyd George; the Play-Doh Peel – Gillian Wearing’s effort is.

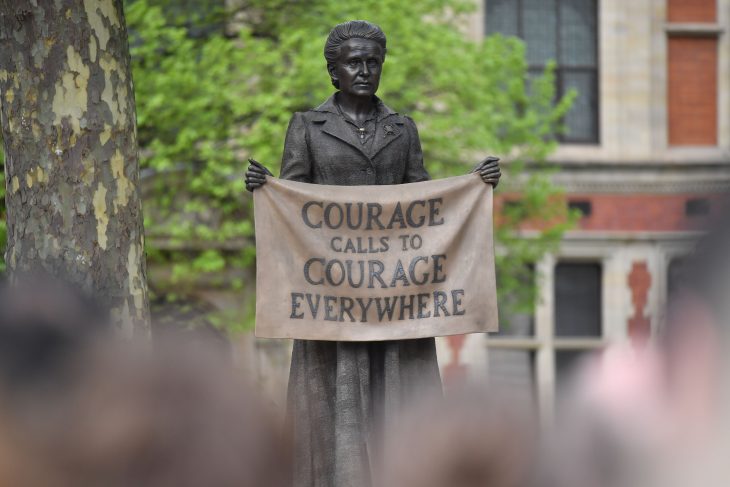

Yet it is distinctive. See the trademark Wearing sign, a dirty cloth in bronze on which the words ‘Courage Calls To Courage Everywhere’ are imprinted. The origin of this visual tick can be found in Wearing’s early photo series ‘Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say’, many of them rather sweet, in which ordinary Brits – shoppers, passersby – reveal their true thoughts on a bit of card that they flash for the artist. ‘I’m desperate’ reads the statement of a smug banker. It was a wry, modest, slightly undercooked, bit of conceptualism. Repression made visible. All very English.

Much of Wearing’s best stuff is like this: about what we bury – about inhibition, masks, how we can really get to know other people. Rebel against your eyes, many works demand, while appealing to those very same eyes.

Which is maybe the oddest thing about this statue. The point about Wearing’s output, especially the photos, was to destabilise the image – as well as the sign. What can we trust? Where’s the reality? Using this trope to display Fawcett’s call to arms immediately undermines the message. Are these words, as in every other Wearing work, what the bearer thinks only inwardly? Not outwardly. And if so, how courageous is that?

Also, doesn’t Fawcett look rather uncourageous? Rather than hurling the words into the air, she’s holding up a bit of fabric. I could think of more courageous poses. And that grip. I tried it earlier. That’s not how you grip a banner that you want people to see. No one grips fingers-to-palm (except maybe a four-year-old), but fingers-to-thumb.

Gilliam Wearing is not a sculptor. She has made sculptures, sure, but I’ve ‘played’ the Hammerklavier, it doesn’t make me Mitsuko Uchida. Anyway, the proof is in the pudding. This sculpture very much looks like a sculpture made by someone who isn’t a sculptor. Aesthetically it’s timid. Technically, ponderous. Conceptually, confused.

Still, it’s no worse than the execrable trio of statues behind her of Peel, Disraeli and Palmerston. I guess if women really want equality in the realm of mediocrity, public art is as good a place to start as anywhere. Also, it gives The Spectator one more entry for this year’s What’s That Thing? Award.

Comments