Literary pseudonyms have been on my mind lately, for a couple of reasons. The first is Salman Rushdie’s revelation that he chose ‘Joseph Anton’ as his cover name when in hiding during his fatwa, in tribute to Messrs Conrad and Chekhov. The second (and brace yourself, because this is going to hurt like pluggery) is that my own literary alter ego, Charlie Croker, has a new book out. Why do writers use pseudonyms, and how does it feel to see a book you’ve written get published with someone else’s name on the cover?

Strictly speaking this isn’t what happened to Rushdie. Joseph Anton was his actual pseudonym rather than his literary one; his fictional books continued to appear under his real name, while his real life was lived under a fictional one. But his recent memoir blurred the lines, being published by Salman Rushdie, titled Joseph Anton, and written in the third rather than the first person. Also in the news this year, for a rather more final reason, was Gore Vidal, whose obituaries reminded us that his detective stories were published under the name Edgar Box. This was to get round the fact that many newspapers were refusing to review his books after the controversial The City and the Pillar. Fear of media and/or public reaction to your true identity is the most obvious, and one of the oldest, reasons for using a nom de plume. George Eliot came into being because Mary Ann Evans worried she wouldn’t be taken seriously as a woman. Over a century later the same concern surrounded the Harry Potter novels, though it was actually Bloomsbury rather than Joanne Rowling herself who insisted on the change. Boys wouldn’t take stuff about wizards from a woman, would they? The only problem was that Joanne had no middle name, so invented the K in tribute to her grandmother Kathleen. As a sign of just how strongly pseudonyms can take hold of you, when taking the stand during the Leveson Inquiry the author gave her name as ‘Joanne Kathleen Rowling’.

This ‘who am I?’ question is potentially tricky. As a famous actor once said, ‘I have spent the greater part of my life fluctuating between Archie Leach and Cary Grant, unsure of each, suspecting each.’ Writers sometimes have the same problem. The American Stanley Martin Lieber started producing comic books under the name Stan Lee, intending to turn to ‘proper’ writing as himself. Only trouble was, his comics became massively successful (he’s the creator of Spider Man, X-Men and the Hulk, among many others), and the serious literature never happened. In the end he changed his legal name to Stan Lee.

Embarrassment plays its part, too. Eric Blair became George Orwell because he didn’t want his family shamed by his account of life as a tramp in his first book, Down and Out in Paris and London. Then there’s the problem of being too prolific. Stephen King was churning out so many books that his publishers didn’t think the public could take the pace. So some were published under the name Richard Bachman (the surname taken from Bachman-Turner Overdrive, the 1970s band beloved of Smashie and Nicey, and indeed Stephen King). I’ve yet to discover the reason for one of my favourite pseudonyms – Colin Dale, the 1920s Spectator book reviewer who was actually T.E. Lawrence. When I say ‘reason’ I mean the reason he used a pseudonym at all. The actual thinking behind the name is known, and is beautiful: while stationed at RAF Hendon Lawrence used the nearby Tube station called Colindale.

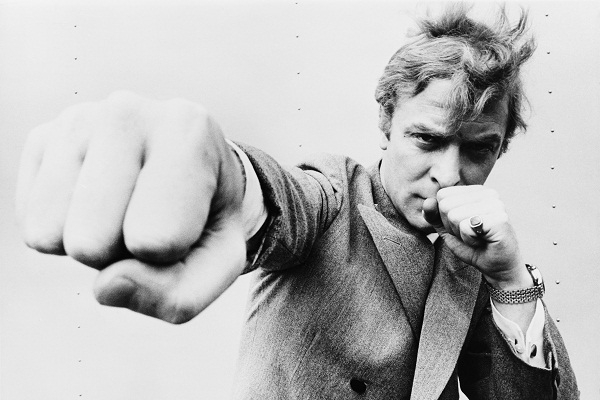

But another category of name-change – the one I fall into – is that of genre. There’s no attempt to conceal identity, you just want to signal to potential readers that if they’re expecting chalk, they may be disappointed to get cheese. Iain Banks, for instance, inserts his middle initial M (standing for Menzies) when he publishes science fiction, and drops it for his ‘normal’ novels. (He’d originally wanted to use the ‘M’ on his first novel, The Wasp Factory – if that can be called ‘normal’ – but his publisher thought it too ‘fussy’.) And so it was that when I had a loo book coming out at about the same time as one of my novels, my agent suggested a nom de plume. Good idea, I said. Which nom, though? Eventually I settled on Charlie Croker for the deeply profound and intellectual reason that it’s Michael Caine’s character in The Italian Job. (‘Michael Caine’ itself, of course, being a pseudonym. The man born Maurice Micklewhite had for a while been acting as Michael Scott. But during a call to his agent from a Leicester Square phone box he learned that there was already one of those in Equity. ‘You’ve got to change your name again,’ said the agent. Scott looked up to see that the Odeon Cinema was showing The Caine Mutiny. Decision made.)

For a very brief time it felt strange, thinking that a book I’d written (even one as slight as a football-based tome aimed at the cistern) would hit the shelves with a different name on it. But then I came to see it as fun, a game, a bit of a jape. After that, as Charlie published more loo books, the conceit began to feel a little more – though only a little more – substantial. Croker became … well, not a real person, rather a real way of denoting that this was a different side of the same person. Denoting to myself, that is; it was a useful discipline in planning the books. Broadly speaking, Croker publishes short books of trivia, while I publish longer books that are essentially trivia too, just linked together with pseudo-intellectual waffle. Charlie’s latest offering is I Didn’t Get Where I Am … (available in all good bookshops, and quite a few ropey ones too). It’s a collection of facts about how the rich and famous achieved their success. Chopin sleeping with wedges between his fingers to widen their span. Robert Maxwell having 5 phones on his desk, 3 of which were unconnected so he could conduct fake conversations with world leaders to impress visitors. That sort of thing.

The most intriguing aspect of Mr Croker’s existence has been his photograph. This didn’t apply for the first couple of books, as he didn’t appear on the cover. Nor did he on the next one, but when a magazine got me to write a piece plugging the book, and hurriedly needed a photo, I had no choice but to supply a shot of my own ugly mug (never a good idea, even under my real name). When my agent was redesigning his website, though, and wanted author photos, we decided to have some fun. For Charlie’s listing, we used a shot of the great British character actor Fred Emney (who was also in The Italian Job, as it happens). Emney seemed to capture Croker’s personality, as much as I’d ever thought that through. I’ve since redesigned my own website to make it clear that Croker and I are in fact the same person, so the Emney photo no longer makes sense. But I do love it, so in that corner of the web it will remain Mr Croker’s embodiment.

Richard Bachman’s jacket photo, incidentally, was posed by a business associate of Stephen King’s agent. I used to joke with a friend of mine about him doing the same for Charlie. It gave me an idea for a novel: the ‘fake’ author gets a taste for the fame, takes over the identity completely by writing a book of his own using the pseudonym, which sells even better than the previous ones … war between the fake fake and the real fake … but of course the real fake can’t fight in the open because the whole point of him using a pseudonym in the first place was that he wanted to conceal his identity …

Must get round to writing that one day. But will I use a pseudonym for it?

Comments