Ever since a consensus emerged that trees and, by extension, their ecosystems, were both vastly interesting and badly threatened, great tottering logpiles of books about woods or individual tree species have seen the light of day. Of these books, one of the most influential has been The Hidden Life of Trees (2018), written by Peter Wohlleben, who for many years has looked after a forest in the Eifel mountains in Germany.

I read that book with interest, and needed no persuading that woodland trees form, in effect, a community, both as a result of the scents they give off and the interactions between their roots underground. And the book contained a timely plea that we should think much harder about the importance to the planet of long-established old-growth (as opposed to planted) native forests and woodland.

However, the author’s attachment to the Pathetic Fallacy (the titles of chapters included ‘Friendships’, ‘Social Security’, ‘Love’) made me so frantic that I could sometimes cheerfully have thrown the book across the room. I recognised that my anthropocentric thinking about trees required a considerable shift, but I could not go so far as to ascribe to trees consciousness, or a moral value to what he depicts as choice. (I should say that, over the past 25 years, I have planted a ‘shaw’ of 400 native trees at the end of my garden, and this work ranks among the more worthwhile things I have done in my life.)

‘Twitch your nose in readiness for a sensual relationship with our cousins, the trees’

Now the inquiring Wohlleben has turned his attention to what woodland can do for us. In The Heartbeat of Trees he explores humanity’s past relationship with woodland and, building on that, all the ways that we can again connect more closely with trees — for our benefit and theirs. ‘The ancient tie that binds us to nature is not and never has been severed. We have just ignored it for a while.’ Anyone who spends time among trees senses how good that is for their physical health and mental wellbeing; Wohlleben demonstrates how.

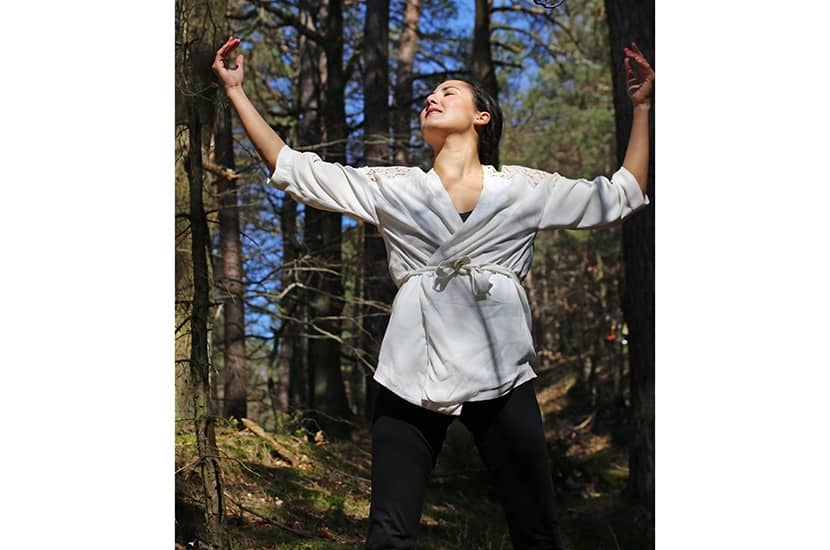

He is kinder about human capabilities than I expected, averring that our senses are much better than we suppose, before encouraging us to extend their reach and sophistication by patient trial and practice. We should, he says, spend time in woodland and forests, both at night and in the day — he calls this ‘forest bathing’ — and learn empirically something of the complexity of trees as well as their interconnectedness, with each other and their environment.

What he writes is occasionally difficult — much of it is gleaned from current scientific research — yet always written in an attractive, easy style, which is a tribute also to the translator, Jane Billinghurst. What is more, only rarely did I feel an impulse to throw the book around as, for example, when he wrote that ‘the root tips feel, taste, test and decide where and how far the roots will travel’.

In the last quarter of the book, the reader is treated, if that is the right word, to descriptions of ancient woodland around the world which are under threat from timber commerce and climate change. The tale is unutterably depressing. At one point, Wohlleben refers to woodland conservation as ‘self-care’; perhaps only if enough of us understand it as such, will ‘old-growth’ forests survive anywhere, since the subtext behind these accounts is the relentless selfishness of man.

One way that species of trees ‘communicate’ is by giving off what Wohlleben calls ‘scent-mails’, and tree scent is the subject of Thirteen Ways to Smell a Tree. David George Haskell, a Briton who lives in North America, writes in a manner reminiscent of Wohlleben: ‘Aroma is the primary language of trees. They talk with molecules, conspiring with one another, beckoning fungi, scolding insects and whispering to microbes.’ He enjoins the reader to ‘twitch your nose in readiness for a journey into a sensual relationship with our cousins, the trees’. (According to Wohlleben, I share a quarter of my genes with trees, which makes me a cousin, I suppose; although it also means I may be the daughter of a banana.) And not just twitch your nose, but your ears as well, since Professor Haskell has invited the violinist Katherine Lehman to compose music to accompany each of the essays. These compositions are to be found on Haskell’s website or in the audiobook.

The book discusses the aromas of 13 trees or tree products, including horse-chestnut conkers, woodsmoke, old books and, amusingly, the cardboard pine tree that hangs from the rear-view mirror of every taxi across the world. Not surprisingly, as a professor of biology and environmental sciences at the University of the South in Tennessee, Haskell is at his best when describing the chemistry of scent, and the effects it has on us. Notwithstanding that the prose swithers between the poetic and the downright overheated, there is much of real value in this book, full as it is of minute observations and careful reflection.

Ancient trees, which woodmen have been successfully persuaded to spare, have singularities which appeal strongly to us, if only because of the associations, myths and tales that they have acquired along the way. Mark Hooper has counted on this fact to attract tree lovers to The Great British Tree Biography: 50 Legendary Trees and the Tales Behind Them. He believes that these 50 vignettes tell us much about our country and ourselves: inter alia, he describes the sycamore in Barnes memorialised as the scene of the car crash that killed Marc Bolan, the oak that W.G. Grace hit with a cricket ball at Sheffield Park in Sussex, and the oak at Holwood House in Keston under whose boughs William Wilberforce told William Pitt the Younger of his intention to bring forward to parliament a bill to abolish slavery.

Reading this book will pass a pleasant hour or two, as you learn about an oak in Motherwell in whose shade Covenanters held clandestine conventicles during the ‘Killing Times’, or a ginkgo in the Royal Dockyard, Pembroke, presented in 1877 at the launch of a warship built there for the Imperial Japanese Navy. There is nothing deep here, the connections with important historical events are sometimes tenuous, and the information occasionally inaccurate — the sycamore of ancient Egypt is a kind of fig and not the maple-relative that we know — but it is an agreeable read, nevertheless. The colour illustrations by Amy Grimes, which have something about them of Davids Hockney and Inshaw, add to the book’s charm.

Comments