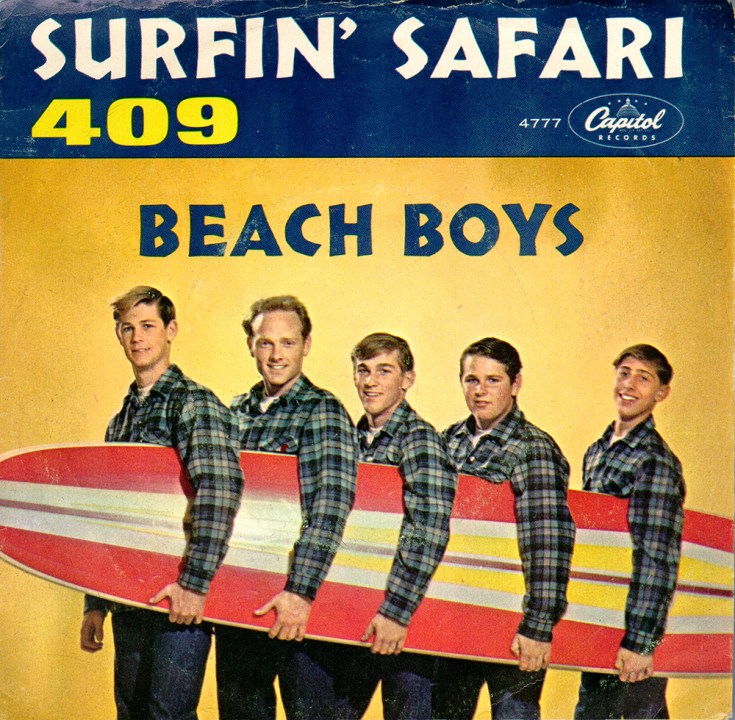

Film noir was the term coined by the French in the late 1940s to describe the genre of Hollywood crime movies which probed the darkness that lay in the shadows cast by all that bright Californian sunlight. The Beach Boys, who broke through in the early 1960s with a repertoire that hymned, in five-part harmonies, the Golden State’s promise of sun, sand and waves, bronzed bodies, beach-party ‘babes’, hot rods and open highways, were – and remain – the quintessential Californian band. But their story, an unhappy family saga featuring the three Wilson brothers (Brian, Carl and Dennis) and cousin Mike Love, is, like that of California’s itself, as dark as it is light.

Their presiding musical genius, Brian, died in June. He was left deaf in one ear as a child, following a beating by the bullying Murray, a nickel-and-dime songman and the band’s future manager. As he grew older, Brian was plagued by what we now call mental health issues and problems with substance abuse. And the work that he intended to be his musical landmark, Smile, an album recorded over the long and troubled months of 1967 in sessions conducted in conditions close to insanity (the studio turned into a sandpit, musicians wearing fire helmets, percussionists issued instructions to play ‘like jewellery’), was famously scrapped and not completed for 40-odd years. Whole books have been written about Smile alone and it is to Peter Doggett’s credit that he doesn’t labour over the details of its ignominious demise.

In fact, he sees the greater tragedy not in the loss of that single record but in the subsequent road not taken after a creative streak in the early 1970s. It was then that the group, by now composing far more collectively, produced three excellent albums: Surf’s Up (1971) Carl and the Passions – ‘So Tough’ (1972) and Holland (1973). The last, despite being recorded in Amsterdam, contained the sublime ‘California Saga’. (You could take the Beach Boys out of California but you couldn’t take California out of the Beach Boys.)

Sadly, Doggett writes, these ‘efforts to outrun their past ended in failure’. Keen to cash in on the 1973 success of the soundtrack album to George Lucas’s period piece American Graffiti, their former label Capitol put out the early hits-stuffed ‘oldies’ compilation Endless Summer the following year. At a stroke, the Beach Boys were ‘pigeonholed… as the standard-bearers of summer, surf and nostalgia’, the group, led by Mike Love, becoming ‘a vehicle for lucrative but ultimately deadening repetition’.

Love has long been a hate figure to some, and the villain to Brian’s hero, in plenty of other books about the band. But one of the refreshing things about Doggett’s survey is that he is generous about Love, a devotee of transcendental meditation (once even hospitalised by fasting), whose drive was central to the group’s initial success and long-term survival. Though Brian receives top billing in the subtitle, Surf’s Up is very much a group portrait. While moving chronologically through the band’s career, it’s interspersed throughout with informative chapter-length profiles of each member, with proper due given to the contributions of such long-standing non-Wilsons as Al Jardine and the 83-year-old Love lieutenant Bruce Johnson.

In addition, there are sections that delight in riffing on particular themes, be they the group’s politics, ‘strange obsession with food’, fashion sense (or lack of it) or Love’s penchant for hats – weight gain and premature hair loss being among the lesser troubles to have afflicted these musicians in their prime. A chapter titled ‘Mike Love’s Greatest Ideas’ offers a list of the man’s more egregious pet projects and money-making schemes since the late 1970s. Among them was a thankfully never realised children’s album with the Smurfs, to have featured songs such as ‘Smurfing USA’ and ‘Smurfer Girl’.

Descriptions of long legal battles between band members can often sink rock biographies. As the author of You Never Give Me Your Money, a take on the Beatles’s writ-cluttered end in 1970, Doggett knows how to handle a brief and scythes through the thickets of suits and countersuits. He sums up the Beach Boys’ position c. 2003: ‘Everybody now seemed to have sued everybody else, and everyone seemed to have both won and lost.’

He also offers a thorough analysis of one of the most disturbing episodes in the group’s history: Dennis Wilson’s relationship with the cult leader and would-be pop star Charles Manson. The evidence Doggett presents suggests that Dennis, who transformed one of Manson’s tunes, ‘Cease to Exist’, into the haunting Beach Boys’ track ‘Never Learn Not to Love’, was far from honest about the extent of his involvement with ‘the family’.

His own family was messy enough. The group’s drummer and lone surfer, Dennis was the middle of the three brothers and the handsome, bad-boy rebel of the pack. Brian was the eldest, a put-upon musical savant who never felt capable of satisfying their exacting father’s standards. The youngest was Carl, the chubby and ever conciliatory peacemaker both in the home and in the band, with the voice of an angel and the physique of a schlub. But Dennis was a hedonistic alcoholic, a soak who drowned while swimming off Marina del Rey under the influence of alcohol in 1983. His Pacific Ocean Blue, a solo album, whose reviews on its release six years earlier were often damning, has since been justly hailed as a classic. Along the way, Doggett offers his own judicious reassessments of the Beach Boys’ back catalogue, pronouncing their Bee Gees-esque disco version of ‘Here Comes the Night’, greeted on release in 1979 as a ‘terrible travesty’ and ‘commercial pandering of vilest kind’, as ‘tremendous’. I happen to agree with him.

The role of the controlling, avaricious psychologist Eugene Landy, who sought to claim co-authorship (along with his girlfriend) of chunks of the Wilsons’ songs, is dealt with brusquely. Doggett confesses now to feeling troubled by the pleasure he took at seeing Brian’s seemingly triumphant return to live performance in 2006. The final shows, he feels, amounted to ‘the modern equivalent of a visit to a Victorian asylum’, with the singer sitting ‘motionless and silent amid his magnificent musicians, his presence at the heart of the stage like a gaping sinkhole’. Brian’s gone now. But, just as in those last concerts, ‘his music continues without him’. And this book is as good a place as any to appreciate the breadth and depth of it, if also to understand what it cost him.

Comments