Tough job being a disused prime minister. John Major has resisted the temptation to flounce off in a sulk, or to play the international peacemaker, or (as Harold Macmillan was said to do during the 1970s) to fantasise about a glorious comeback urged on him by a despairing populace eager to rediscover its lost greatness. Instead, Major has become a social historian. After a book on cricket he now offers us a personal history of the music hall. His father, Tom Major (b. 1879), made a living as a comic artiste for over 30 years, and his recollections are the starting-point for Major’s investigations.

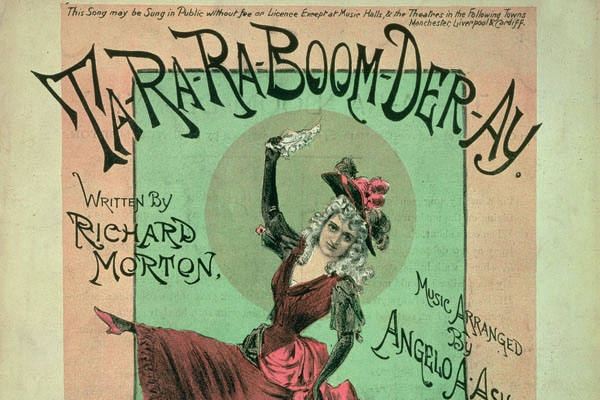

Music hall grew out of the glee clubs and saloon theatres of the 18th century where ‘catches’ (hummable melodies) were played to boozing crowds by impromptu artistes. Publicans realised that by hiring talented performers they could attract more customers and keep the cash rolling in at the bar. By the mid-19th century, a huge market for live entertainment had developed among the working classes, who now had time on their hands and cash to burn. Music hall gave them what they wanted: supper, alcohol, a chance to make a bet, and a parade of singers, comics, street-acrobats, magicians, transvestites and exotic hustlers from all over the world. London was the centre of this ramshackle showbiz boom.

Most music-hall performers struggled to make ends meet, but the big stars could earn hundreds of pounds a week, sometimes playing five or six venues in a single evening. Hansom cabs criss-crossed the city, ferrying the high-earners between theatres.

One performer, after hearing himself referred to as a ‘has-been’, went to nearby park and blew his brains out

Drink and exhaustion terminated many careers. Hangers-on and poor relations were adept at imposing on the generosity of a prosperous star. The fear of failure was ever-present. One performer, after a gig in Glasgow where he heard himself referred to as ‘a has-been’, went to a nearby park and blew his brains out. Few of the big names died elderly, sober and solvent.

The heyday of music hall predates the gramophone, so it’s hard for us to grasp its popular appeal. Here’s a burst of patter by ‘the prime minister of mirth,’ George Robey, a leading star of the Edwardian era, who appeared on stage as a defrocked cleric:

Really, I meantersay, let there be merriment by all means, but let that merriment be tempered with dignity, and with the reserve which is compatible with the obvious refinement of our environment.

How familiar that sounds. The insistent rhythm, the homely, chiding tone and the self-mocking bombast are all redolent of Frankie Howerd. Unlike many stars, Robey held conservative views and was labelled ‘a toffee-nosed twat’ by embittered colleagues. He deplored the perverse sentimentality of the public who extolled an outcast but treated a hard-working success as a ‘usurper’. ‘It is never suggested that both men are in places where they deserve to be. In other words, we are witnessing an elaborately organised deification of inefficiency.’

Major offers up lively pen-portraits of all the leading performers — Marie Lloyd, Dan Leno, Harry Lauder and Little Tich — as well as producers like Charles Morton and Oswald Stoll. Though meticulously researched, the book suffers from the author’s dogged impartiality. A womanising impresario named George Adney Payne was satirised in a sketch featuring a pregnant girl and her friend. ‘’Ad any pain?’ asks the friend. ‘Certainly not,’ says the pregnant girl. ‘It’s my boyfriend’s.’ In a stern footnote Major corrects any implied injustice with a dose of magisterial neutrality. ‘This may simply have been malice, as I can find no firm corroboration for such stories.’

The same blandness affects the reminiscences of Tom Major, who was 64 when his son was born. Tom knew Houdini well, but all we discover about the world-famous escapologist is that his ‘charm and skill’ were admirable. Another colleague, Vesta Victoria, specialised in innocent songs which in performance, we’re told, ‘were full of innuendo that audiences would readily have understood’.

Music hall died swiftly after the Great War. The arrival of jazz, the radio, and the talkies consigned it to the history books. As Major points out, its spirit lived on in acts like Morecambe and Wise, Bruce Forsyth and Shirley Bassey. Even Top of the Pops, with its mixture of infectious melodies and knowing silliness, would have worked perfectly in a Victorian theatre. One of the show’s earliest stars was a cross-dressing singer whose anthems of escapist romance were hugely popular: David Bowie is a classic music-hall act. And his first hit, ‘Space Oddity’, begins with the line, ‘Ground control to Major Tom.’

Comments