‘You’re never alone with a Strand,’ went the misbegotten advertisement for a new cigarette in 1959. What the copywriter didn’t realise is that smokers often smoke to be alone. As Mass Observation had reported a decade earlier:

In an increasingly gregarious world, where fewer and fewer habits and pastimes are entirely individual, the cigarette remains for most people a pleasure that, whatever its social significance, can be enjoyed in entire solitude, and a pleasure that remains entirely individual.

At the time, 80 per cent of British men and 40 per cent of women were regular smokers. Smoking was not just a means of inhaling death and of escaping the dead hand of others’ sociability, but briefly put the unbearableness of life behind a smoky veil. When fags were cheap, no wonder they were especially popular among the working poor, for whom snatched moments of peace and quiet were breathing spaces from otherwise unremitting grind, noise and worry.

True, smoking had risen in popularity during the second world war as a means of brokering sociability at a time of troubling loneliness. After the war, its continuing vogue was fuelled by an opposite impulse — to disconnect from the hell of other people. Like masturbation (which David Vincent unaccountably omits from his book), smoking is a solitary pleasure, though unlike masturbation sometimes acceptable among others.

The diabolical genius of smartphones is to allow us to be present and absent at once, solitary and gregarious at will

Vincent regards smoking as the defining example of abstracted solitude, the capacity to remove the self from present company. It’s no coincidence that the cigarette packet is roughly the same size and shape as today’s fetish object, the smartphone. But while the smartphone offers abstraction from others, it is also the culmination of another kind of solitude. The penny post, news-papers, telephone, film, television, the internet and iPhones have offered networked solitude, keeping us in touch with distant people while letting us remain alone. The diabolical genius of smartphones is to allow us to be simultaneously abstracted and networked. We can be present and absent at once, solitary and gregarious at will.

Such paradoxes abound in this beautifully written, nuanced and now topical history. Do we have the right stuff to be alone without being lonely through quarantine? Vincent shows how our ancestors cultivated solitude to give respite from the world, to reform character in prison or to commune the better with God in retreat. Perhaps us self-isolators can learn from their examples.

Very few of us, though, have the mental resources of Hertfordshire’s leading Buddhist hermit, Jetsunma Tenzin Palmo (born Diane Perry), who spent 12 years in a 10’x 6’ Himalayan cave, surviving temperatures of -35°C. But even she, despite such propitious circumstances for escaping human fatuousness, didn’t achieve moksha. We self-isolators haven’t chosen to be alone but, like prisoners in solitary confinement, whose shadowy history Vincent traces, are stuck in circumstances to which we’re temperamentally unsuited.

Rather than Buddhist nuns, we better resemble Don Martin Decoud, the plump dandy journalist of Conrad’s Nostromo. All of Decoud’s reserves of worldly irony and scepticism were useless once he was marooned on a desert island. Despairing, he filled his pockets with silver bars and, as Conrad puts it, ‘disappeared without a trace, swallowed up by the immense indifference of things’.

And yet, even before Covid-19, many yearned, like Garbo, to be let alone. In the early 20th century 1 per cent of Britons lived by themselves; by 2011, 31 per cent, or eight million, did, many finding in it self-fulfilment rather than a motive for suicide. The Guardian columnist George Monbiot, though, sees in such figures an ‘epidemic of loneliness’. We have lost, he claims, what is essential about humans, namely connectedness. Vincent paints a more nuanced picture:

Men and women decided to live alone in increasing numbers after the second world war because it became practically feasible to do so, and because at different times they preferred their own company to that of their parents, their grown-up children or their unsatisfactory partners.

Loneliness arises, Vincent counsels, when we are marooned by bereavement, or when investment in social and health services declines. One definition of loneliness is solitude continued further than intended: what started as self-liberation becomes a life sentence.

Vincent insists on what Monbiot misses: how essential it can be to remove oneself — if only for the length of a lit cigarette or a game of Candy Crush — from the hard labour of sociability. Hence the popularity of Sylvain Tesson’s memoir Consolations of the Forest, about a man who lives as a hermit in Siberia for six months. Hence, too, the allure of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World that Can’t Stop Talking, in which Susan Cain suggests that the noisome extroverts yucking up their nothingy conversations on buses have their parallel on Twitter. How lovely to escape them — ideally by withdrawing into solitude to read. The BBC-Wellcome Trust Rest Test in 2016 reported that respondents across 134 countries found reading the most restful activity. Social media not so much.

Vincent’s book is a treasurable flip-side to the sound and fury that historians usually focus on, a quiet history of solitary activities: walking, fishing, gardening, needlework, embroidery, stamp-collecting, crossword-solving, dog-walking, jigsaw puzzles, DIY and reading. But the author is always sensitive to how recreational solitude risks becoming a form of conspicuous consumption for wealthy eccentrics. Not all of us can afford to circumnavigate the globe single-handed or have an instagrammable Hornby train set in the attic.

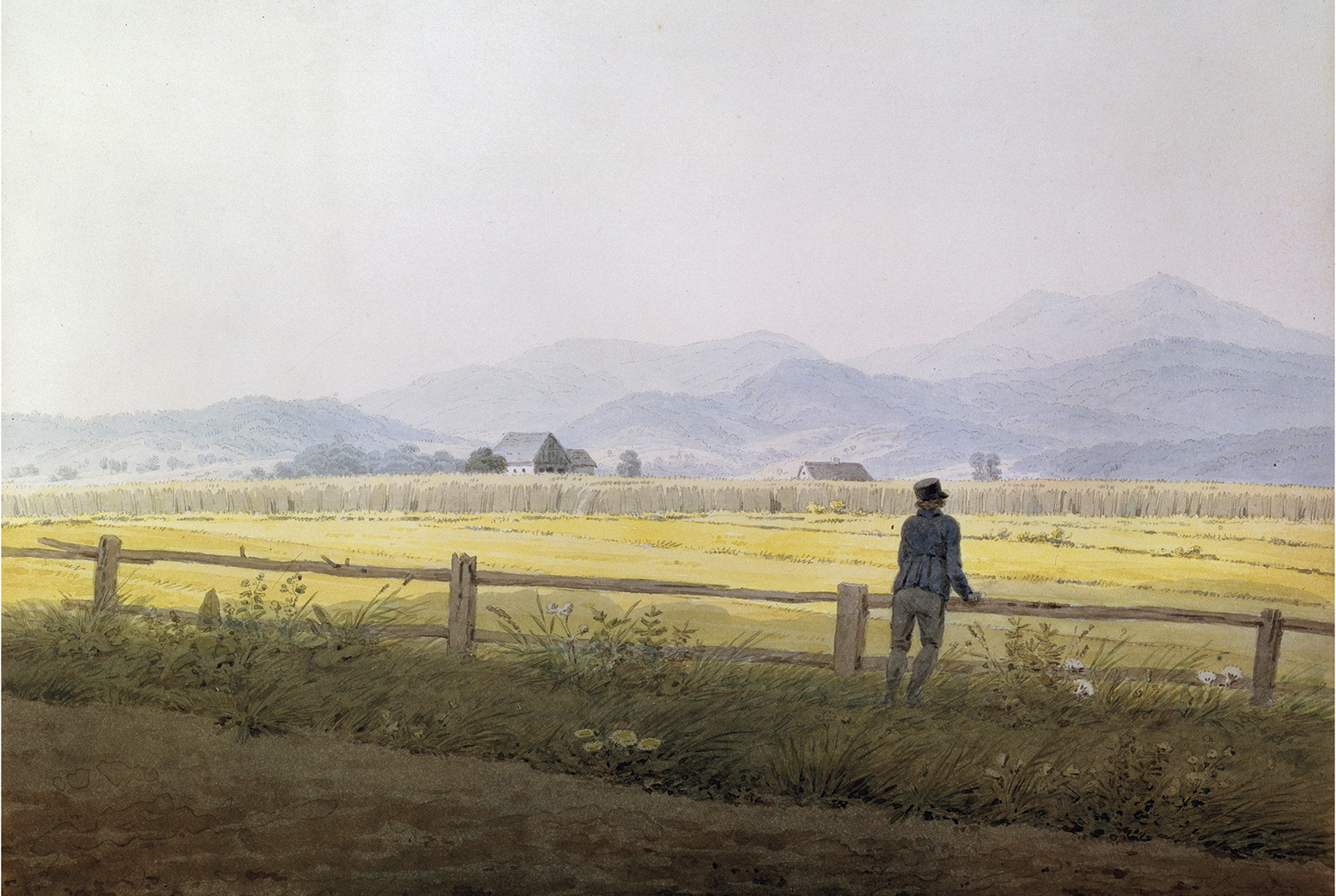

He’s attentive too to how peace and quietness have long been sought by those recuperating from workplace or domestic labours. When there is no nature with which to commune, silently staring into the middle distance in the park, with cigarette and/or dog as foil, may not be as mindless as it initially looks.

Compare such seeming mindlessness to today’s new cult of mindfulness, which Vincent calls ‘solitude tailored to late modernity — eclectic, privatised and readily commodified as an avalanche of print, supportive objects, digital media and courses that flood into the market’. The austere virtuosos of solitude — Wordsworth wandering lonely as a cloud or Tenzin Palmo meditating in her Himalayan cell — needed no such fripperies.

Comments