When the truth of Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path was called into question, many commentators jumped in with both feet; as Sam Leith astutely pointed out in The Spectator, there is nothing the English like so much as a good disappointment.

‘So, we twisted our story.’ It ties in with the phenomenon of confabulation

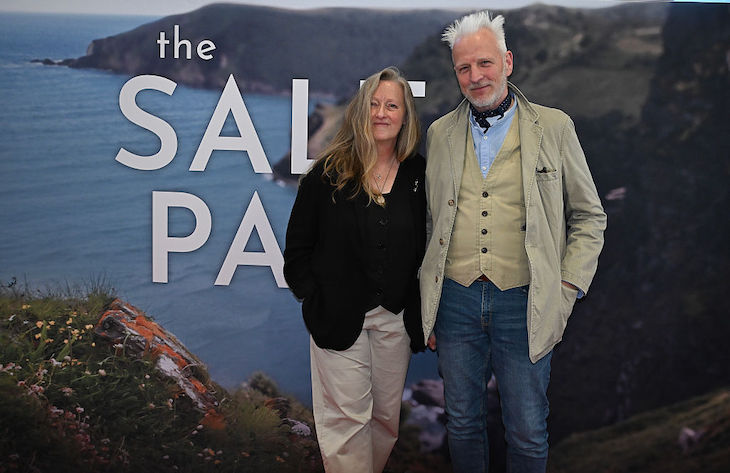

Winn continues to contest the allegations which have cast doubt over the truth of the 2018 memoir. She also issued a statement talking of ‘the physical and spiritual journey Moth (her husband) and I shared, an experience that transformed us completely and altered the course of our lives. This is the true story of our journey’.

I believe her about the essential truth of the actual journey, both in The Salt Path and in the later book Landlines that I reviewed in The Spectator. But I can also see how she might have been led to dissemble so badly about the circumstances that led to that journey. There is a clue no one has noticed in an interview she gave to Big Issue back in 2017, when she launched the first book and was completely unknown:

We were regularly asked: “How come you have enough time to walk so far?” When we told the truth, children were held closer, dogs retracted on leads, doors were closed and conversations ended very quickly. The view from the rural idyll is that losing your home and becoming homeless makes you a social pariah.

So, we twisted our story [my emphasis] – we had sold our home and become homeless, and the general view then was that we were inspirational. It became a game, to observe how changing one word changed reactions.

‘So, we twisted our story.’ It ties in with the phenomenon of confabulation with which I’ve long been fascinated and had some considerable personal experience of when my father developed dementia – and wrote about in One Man and a Mule – as it is often associated with that disease.

Confabulation is a disturbance of memory, defined as ‘the production of fabricated, distorted or misinterpreted memories about oneself or the world.’ One of its most salient features is that if you repeat a story often enough, to yourself or others, you come to believe it is true because you remember telling it – even if you do not want, or are not able to remember the actual events it describes. You remember the telling of the story more than you do the actual events.

I suspect Raynor may have become so adept at telling an acceptable story to those she met on the walk that, when it came to writing the book, she maintained the confabulation. The story became yet more ‘twisted’.

Not only may this have been fatal to her reputation – for both film and book were marketed very heavily on the veracity: ‘this is what real life is like’ – but it was completely unnecessary.

All readers need to know is they have no money and no home, so begin walking. There was no need at all to explain the circumstances, let alone construct a false narrative in which they were the victims rather than, as it seems, allegedly the perpetrators in this messy story.

The issue of whether Moth does or does not suffer from a degenerative disease and whether walking helped alleviate this seems a much more tendentious and tasteless one for the Observer – which first brought these allegations to light – to raise as a collateral claim. Medicine and therapeutic cures can behave oddly. My own father was given a prognosis of seven years for his vascular dementia. He lived for another ten years beyond that. And Moth did not write this book.

I would like to remember Winn for the attention she brought to the phenomenon of rural poverty – which I tried to do myself in my books about walking across England.

This is the succeeding paragraph in the Big Issue Interview:

Sheltering inland away from a storm, we discovered an invisible community. A group of people, who lived and worked in a beautiful spot, but couldn’t afford to rent even a room in an area of high-value holiday rentals. After work, they drifted along a wooded valley to sleep in hammocks strung in sheds, horse boxes, and grain silos. Not travellers, or dependent rough sleepers, but average people who just couldn’t afford a home in the countryside where their livelihood was.

This story also raises some questions about publishers’ expectations of travel books; their increasing demand that there always has to be some redemptive arc, which may explain, though not excuse, why she felt she had to give a moral imperative.

There was a time when a travel writer would set off with a spring in their step: Coleridge knocking the bristles from a broom in his impatience to make it a walking stick; Laurie Lee heading forth one midsummer morning; Patrick Leigh Fermor singing as he headed down a lane.

To travel was an expression of freedom and exploration; to step out of the front door the beginning of a great adventure.

Not any more. Today’s travel writers come troubled and weary before they’ve even begun. A journey can no longer be a jeu d’esprit. It has to be undertaken to expiate some deep trauma. It is almost as if, in today’s New Puritanism, it has to be painful. One thinks of the old nursery rhyme: ‘Wednesday’s child is full of woe/ Thursday’s child has far to go.’

Recent bestselling examples of this genre have all followed the same principle: Cheryl Strayed’s Wild: From Lost to Found treated walking as necessary psychotherapy; Guy Stagg’s The Crossway was billed as ‘a journey to recovery’. Raynor’s The Salt Path, telling of a couple escaping from eviction and illness, is following the call from publishers for more ‘miserylit’ travelogues.

If anything comes out of this very sad tale, perhaps it can be that we no longer demand that all our travel books begin in tragedy; and that the journey can just be taken for its own sake.

Hugh Thomson is the author of The Green Road into the Trees (Random House) about walking across England, which won the first Wainwright Prize

Comments