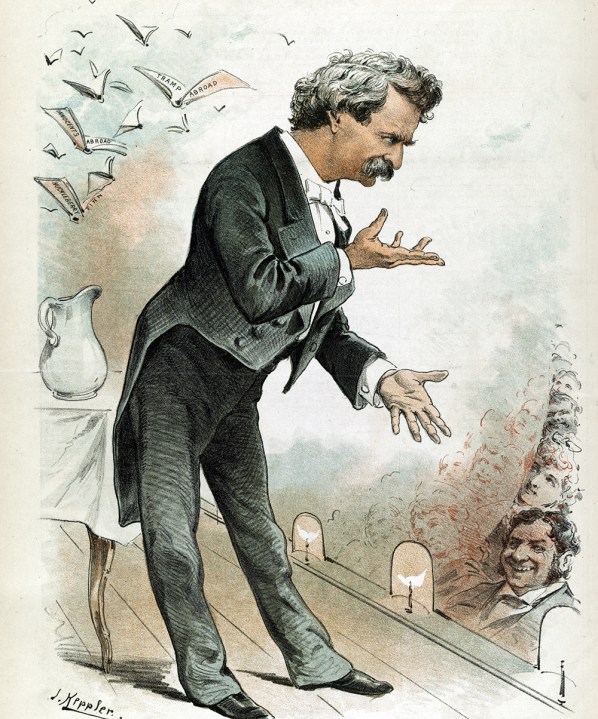

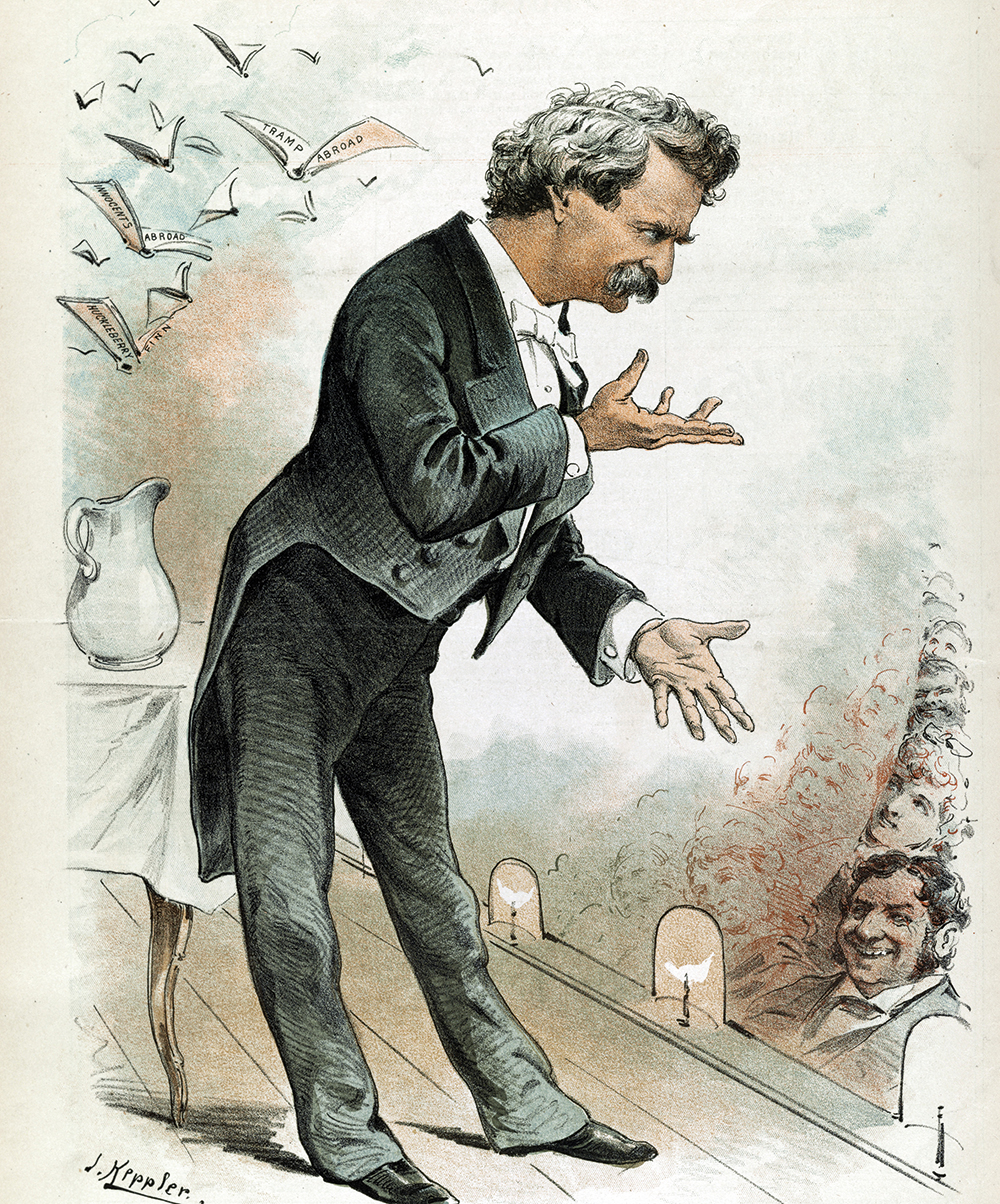

You know Mark Twain’s story. You’ve got no excuse not to; there have been so many biographies. Starting in the American South as Samuel Clemens, he took his pen name from the call of the Mississippi boatmen on reaching two fathoms. His lectures, followed by his travel pieces and novels, enchanted America and then the world.

As a southerner, his principled stance against slavery gave him moral authority. The famous ‘Notice’ to The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn – ‘Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished’ – was swept aside, so that persons like H.L. Mencken could straightfacedly describe it as ‘the greatest novel ever written in English’. Though made rich by his writing and an ambitious marriage, Twain lost an enormous amount of money as a result of bad speculation. He died as famous as any author has ever been.

His lessons of vividness and concision have not always been well learnt. Some biographies, including this one, stretch Twain’s life out to 1,000 or even 2,000 pages of adoringly documented quotidian footling. In his funniest piece of literary criticism, Twain wrote of a piece by James Fenimore Cooper: ‘Number of words: 320. Necessary ones: 220; wasted by the generous spendthrift: 100.’ You wonder how a biographer could quote this and then sum up Twain’s objection to Cooper’s prose as ‘stiff, bloated and turgid’. Bloated and turgid of course mean the same thing.

Twain’s life demonstrates all sorts of things, but a very conspicuous one is the spell that Charles Dickens cast. This goes unrecognised by Ron Chernow, but it is undeniable. Twain took his future wife to one of Dickens’s touring performances and afterwards modelled his career on the great man. Where Dickens took excerpts from long-published novels to the stage, Twain started with comic stage performances. It is sometimes stated incorrectly that the lectures came as a result of Twain’s celebrity as an author; in fact he hired a hall in San Francisco in 1866, before his first book. Dickens had combined writing novels with working as an editor and publisher, promoting Mrs Gaskell and Wilkie Collins among many others. Twain, imitating him, invested in and funded a publishing house which discovered nobody and contributed to a catastrophic bankruptcy. Dickens succeeded as an editor because he truly valued other writers; Twain failed because he resented and wanted to crush them.

One direction Twain took that Dickens never did was to invest in harebrained ventures, being easily convinced by rancid salesmen. Amusingly, an early scheme was to introduce the American public to the virtues of the South American coca leaf. Twain might easily have been the first crack billionaire. Instead, he poured his own and his wife’s money into a ridiculous typesetting machine, with disastrous consequences.

But the principal – and most painfully obvious – aspect of the debt to Dickens was Twain’s evident fascination with the master’s style. Repeatedly one sees moments when Dickens was fruitfully ransacked. In Twain’s early, very enjoyable travel books, The Innocents Abroad and Roughing It, the suave worldliness of Dickens’s journalism is emulated. This, from Dickens’s greatest reportage, is hisUncommercial Traveller visiting a theatre:

The Pantomime was succeeded by a Melo-Drama. Throughout the evening I was pleased to observe Virtue quite as triumphant as she usually is out of doors, and indeed I thought rather more so. We all agreed (for the time) that honesty was the best policy, and we were as hard as iron upon Vice, and we wouldn’t hear of Villainy getting on in the world – no, not on any consideration whatever.

Pure Twain.

Even the 1880s travel books, A Tramp Abroad and Life on the Mississippi, show the impact of Dickens’s journalism. And one could argue that the shift from the literary, observing manner of Tom Sawyer to the unforgettable narrative style of Huckleberry Finn was enabled by the astonishing stage monologues of Dickens’s ‘Mrs Lirriper’ stories.

Like most British novelists of the time, Twain thought he could only attain literary greatness by writing historical novels. Trollope thought Thackeray’s Henry Esmond would be read when Vanity Fair was forgotten, and Twain’s circle considered he had reached perfection with Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc (‘Wait, wait, till I get a handkerchief’). All in all, Twain was an undeniably great writer who grossly undervalued his talent both as a basis for his literary progress and something that would give him and his family a secure existence.

What had gone wrong? He was, without doubt, passionately keen on making money – so much so that the fortune he could amass from his popularity as a writer and speaker wasn’t enough. It is striking that he much preferred the company of plutocrats and royalty to that of other authors. Though the literary world at that time was immensely sociable, few of his contemporaries make much of an appearance in Chernow’s biography. The encounters with royalty were treasured, but insubstantial – Kaiser Wilhelm II, an admirer, was rather offended by Twain as a dinner guest, and neither Twain nor Chernow quite seem to have understood the Garden Party Only aspect of Edward VII’s invitation to a bunfight on the lawns of Windsor. The ambition to leave writing behind and become a multimillionaire through cranky inventions or consorting with the Rockefellers left Twain an easy prey to fraudsters.

His lack of respect for and interest in his contemporaries also diminished his writing resources. Though he could show genial support to promising newcomers, he invariably turned on them with furious jealousy the moment they attracted the slightest attention. Bret Harte, a delightful writer, who ended up in Glasgow, was cast aside. Poor old George Washington Cable, invited to be the support act on one of Twain’s reading tours, had no idea that he had done anything wrong until Twain used a compliant journalist to abuse him at length in the Boston Herald. Almost everything interesting about new fiction at the time – the French realists, Sherlock Holmes – was dismissed or ignored. Without engaging with anyone but his most devoted fans, Twain’s writing grew duller. He was immensely celebrated – he licensed board games such as ‘Mark Twain’s Face and Date Game’ – and had to deal with enterprising impostors mounting lectures in remote places. But the fame increasingly rested on past achievements.

This is rather an unnecessary biography, coming less than seven years after Gary Scharnhorst’s even more colossal volume. Despite this one’s length, its limitations of interest are frustrating. I don’t expect a biographer to note that Twain’s best friend Joseph Hopkins Twichell had a daughter who married the modernist composer Charles Ives. But it might have been helpful to remind the reader of the immense mischief Twain would cause in the century after his death by his description of Palestine, in The Innocents Abroad, as being devoid of inhabitants, ‘given over wholly to weeds’. And it is misleading to quote Twain’s condemnation of the professional standards of his publishing friend James R. Osgood without noting that Osgood moved to England and bravely published Tess of the D’Urbervilles when no English publisher would.

One scheme was to introduce the American public to coca. Twain might have been the first crack billionaire

Overall, Chernow devotes a good deal of space to the details of Twain’s professional career and speculations, but they remain somewhat lacking in context. It is surprising to me that Twain published many of his books through subscription, or by selling to interested readers in advance. This would have been most unusual in England. Was it just how American publishing worked at the time?

The biography might have been justified by elegance of execution, but it is actually maddeningly pompous and prolix: ‘When Sam Clemens departed from Hannibal, he bore a world of pain, but also a cargo of precious memories preserved intact in his mind, ready for future retrieval.’ Twenty-eight words for a thought that needed ten. Chernow also has very little sense of when a word contains a metaphor: ‘The family didn’t fathom at first what a watershed moment this was that they would remain European castaways for nine years.’ These latent metaphors often make him say the opposite of his meaning: ‘And climb, climb, climb he did, now sealing his sudden eruption into the upper class.’ If you could in some way seal an eruption by climbing, wouldn’t that put a stop to it? Sometimes one even wonders whether he understands a word’s meaning: ‘After Huck Finn, Twain didn’t perpetrate another volume on the reading public for four and a half years.’ Perpetrate? A positive reviewer of Tom Sawyer ‘believed Twain had attained a new plateau with the novel’. Plateau? Did the critic think Twain would be stuck from then on?

Chernow’s evident deafness to tone in an amusing writer is a real problem when he can’t tell the difference between a good joke in Twain and this conclusion to a speech, described as a ‘magnificent punch line’: ‘And if the child is but a prophecy of the man, there are mighty few who will doubt that he succeeded.’ I suppose you had to be there.

The major problem with the biography, however, is not its bloviating tendency but its lack of proportion. Driven, I suspect, by the copiousness of the record, more than 500 pages are devoted to Twain’s final 15 years, during which he published almost nothing of interest. His most engaging period, between The Innocents Abroad (1869) and Huckleberry Finn (1885) is raced through – relatively speaking – in less than half the space.

Much of that last period is an exhausting account of family illnesses, law suits, lubricious correspondence with teenage girls, and one colossal, unsatisfying mansion after another – the first of 13 rooms, then 25, then 28, and finally a rented house for Mrs Twain to die in, ‘magnificent in scale, with 60 rooms’. Twain sued the owner of this one three times after she egged on her donkey to bite his irritating secretary Isabel.

There is no doubt that a biographer has failed when his reader, previously fond of the subject, finishes with a feeling of dislike. In the case of this book there is only one remedy – to pick up The Innocents Abroad again. ‘If you want dwarfs – I mean just a few dwarfs for a curiosity – go to Genoa. If you wish to buy them by the gross, for retail, go to Milan.’ That’s the spirit – enough to make you forgive anything in an author, even his biographers.

Comments