Britons live, we are constantly told, in unprecedented times. Rishi Sunak has become the first person of Asian heritage to be appointed Prime Minister and the third occupant of No. 10 in as many months. Thanks to Brexit, Covid and the Ukraine war, the economy is in turmoil while the trade unions are more assertive than they have been in decades. Sunak’s party is divided, perhaps fatally so, with many Conservative members hankering for Boris Johnson, a more charismatic figure than Sunak and one they consider more capable of rescuing them from likely electoral oblivion. Surely no incoming prime minister has faced a more daunting set of circumstances?

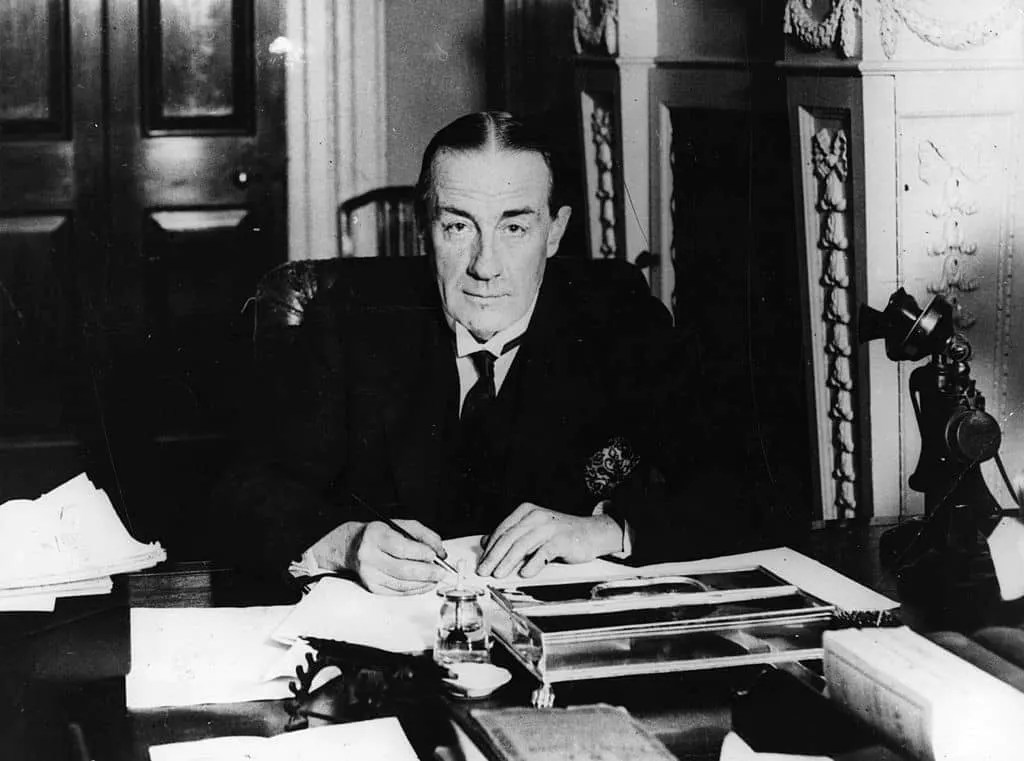

You’d be forgiven for thinking so. But the history books do offer some reassurance for Britain’s new PM. Let me introduce Stanley Baldwin. Conservatives have turned their back on Baldwin, largely because of his association with the appeasement of Hitler. Tories lionise the legend of Churchill: the man who saved Britain. By contrast, Baldwin, if he indeed evokes any memories at all, is seen as one of those lackadaisical leaders responsible for the disaster at Dunkirk.

But before this, Baldwin was the dominant electoral figure of the interwar period and led the Conservatives to three election victories (two of them landslides), voluntarily retiring as prime minister in 1937. Few, though, would have predicted this success when he entered Downing Street in May 1923, just under a century ago. At that point his prospects looked as dim as Sunak’s do now and his situation more similar than you might imagine.

Baldwin realised that calling an election was risky but he believed that the prize of party unity was worth it

Baldwin’s rise to the premiership had been dramatic, largely thanks to his role in ending the coalition government led by David Lloyd George. He led the charge of Conservative MPs at the Carlton Club in October 1922 against their most prominent politicians, including party leader Austen Chamberlain, who wanted to continue their association with the ostensibly Liberal Lloyd George, the man who led Britain to victory in the first world war. But others in the party were unhappy with what Baldwin called Lloyd George’s ‘morally disintegrating effect’ and voted to leave the coalition.

Chamberlain stepped down as leader, triggering an election, but he and his followers continued to hanker for a reunion with Lloyd George, dubbed by some the Welsh Wizard, even after the Conservatives won a majority of 73 seats. Arthur Bonar Law, who succeeded Chamberlain as party leader, became prime minister. Just 209 days later he was, however, forced to resign following a terminal cancer diagnosis and was succeeded by his relatively inexperienced Chancellor, Baldwin, who became the country’s the third prime minister that year.

Despite the impressive Commons majority Baldwin inherited from Bonar Law, his position was weak. The Conservatives remained split over future relations with Lloyd George and the government was massively in debt to the United States thanks to the cost of fighting the world war. Meanwhile, the British economy was still struggling with the consequences of the conflict and millions of trade unionists were unhappy at seeing their real wages forced down and unemployment rising. Few gave Baldwin much of a hope of remaining prime minister for long.

Instead of muddling through and hoping that something might turn up, Baldwin decided to take control of the situation. Within six months of entering Downing Street he called a snap election in December 1923. This was more for political than economic reasons. Baldwin’s aim was to exert his authority as leader and unite the party around an issue they all agreed on: tariffs. His calculation was that this would make any future arrangement with the disruptive Lloyd George impossible.

At that time, the debate over whether to use tariffs to protect the British economy from cheap imports or to allow free trade and the unimpeded flow of goods was a matter more divisive in British politics than even Brexit has proven to be. Baldwin called for a radical round of tariffs ostensibly to protect industry and reduce unemployment. He claimed he needed a new electoral mandate to do this. But in reality, his aim was to burn the bridges between the free trade-supporting Lloyd George and his protectionist Conservative friends once and for all.

Baldwin realised that calling an election was risky but he believed that the prize of party unity was worth it. And he certainly succeeded in this. But the election did not come without its cost: Baldwin lost his Commons majority. While the Conservatives remained the largest party, the election produced a hung parliament and Labour entered office for the first time thanks to Liberal support.

Luckily for Baldwin, the Labour government’s life was short and the ensuing election held in 1924 saw him back as prime minister, this time with a majority of 209 seats. Baldwin used his re-election to craft an image of himself as an emollient, consensual figure – one who could appeal to the middle and working classes. On that basis he managed to dominate politics for a decade, guiding the country through the turmoil of the 1926 General Strike and enfranchising women on the same basis as men.

Quite whether Sunak will ever reach such a position is impossible to predict. Baldwin possessed the low political skills and high strategic ambition Sunak has yet to demonstrate. He also enjoyed more than a bit of luck. Sunak’s position is, in some regards, currently weaker than Baldwin’s was. But, if there is any sort of comparison to be made between 1923 and 2022, Baldwin’s example suggests that taking the risk of calling an election to reset a divided party is one a leader tackling apparently unprecedented troubles might want to consider seriously.

Comments