Michael Simmons has narrated this article for you to listen to.

Scots have, in the past, bragged about having the best education system in the world. Scottish sixth-formers study a broader range of subjects and aren’t forced to specialise too early. And look at our history: the literature, the Enlightenment, our universities, all due to world-class schools. But however true this may once have been, it’s hard to make the same claim now.

Scottish education is in crisis. Confirmation came this week with the PISA international league tables for school pupils in 81 different countries. Up to 10,000 pupils in each system sit tests in maths, reading and science, and the results are a gold standard in comparing schools. Scotland has traditionally come close to England and once led the UK in scores for maths. But now Scots have fallen the equivalent of almost one year of learning behind England. Quite an attainment gap for such similar countries. These results were generous to Scotland, too. The report cites ‘an upward bias of approximately nine or ten points’. So the true picture may be even worse.

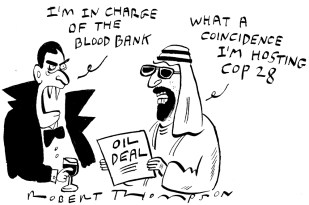

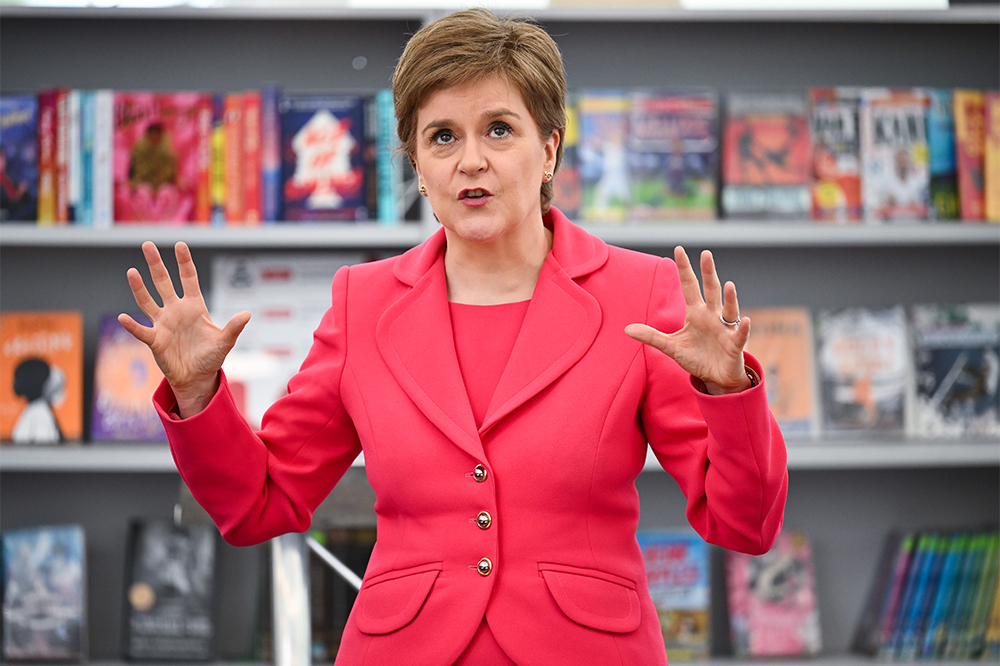

The outcome was described as ‘catastrophic’ by Lindsay Paterson, professor emeritus of education policy at Edinburgh University. The 2010 introduction of the ‘Curriculum for Excellence’ – an overhaul hailed by Nicola Sturgeon as the very latest in teaching methods – seems to have accelerated the decline. The only consolation for Scotland is that the results are not quite as bad as in Wales.

This is not how devolution was supposed to work. Since 1999 the education policies of Scotland and Wales have been decided in Holyrood and Cardiff Bay respectively. The early advocates of devolution thought that, within 25 years, local pupils would be leaving their English counterparts behind. ‘Scottish solutions for Scottish problems’, ran the mantra. Just how different those problems were is an open question, but devolution would test the ‘home rule’ theory. If it worked, England’s neighbours would be improving faster.

Teachers are told to prioritise ‘skills and wellbeing’ over the acquisition of knowledge

Scotland used its new powers to reject the parent-choice agenda. When Tony Blair and later Michael Gove developed self-governing academies, schools in Wales and Scotland remained under local authority control. Then the curriculum reform came. Teachers were concerned at what some saw as dumbing-down masked by grade inflation, but PISA tests cannot be gamed. The maths results showed that England’s pupils have kept steady over the years, in spite of lockdowns, but since 2015 Wales has dropped 12 points (equivalent to six months of learning). Northern Ireland fell 18 (nine months) and Scotland dropped 20 points.

While England and Wales saw improvement, with their maths scores reaching highs in 2018 (before lockdown reversed the trend), Scotland has been on a continuous downward slope since 2000 – falling 11 points (six months) in reading and seven points (four months) in science in just the last four years. Newspapers in Scotland now run tips for parents about how to take teaching into their own hands.

Having spent my school years during Curriculum for Excellence’s rollout at an Edinburgh comprehensive, I have a fair idea of what went wrong. I count myself lucky to have been in the penultimate cohort to take exams under the old system, but the new teaching methods were already in evidence. Teachers are told to prioritise ‘skills and wellbeing’ over the acquisition of knowledge. The premise is that learning is boring and remembering facts, dates and capital cities a waste of time. So Scots saw the old knowledge-based system replaced by ideology fuelled by buzzwords like ‘child-centred’ – as if the old method of building memory, critical thinking and study was not child--centred. Committing knowledge to memory was replaced with iPad skills, and out went academic problem-solving to make room for ‘Learning for Sustainability’, including how to ‘understand the world, the environment and Scotland’s place in it’.

Scotland’s Education Secretary, Jenny Gilruth, tried to pin the blame on Covid’s ‘profound impact on our young people’. Sturgeon was slower to resume classroom education than Boris Johnson. English schools reopened in June 2020 but Scotland waited until after the summer holidays. As the second wave hit, Sturgeon was quick to announce that schools would reopen only for vulnerable children and those whose parents were key workers, while the rest would make do online. In a school year of just 190 days, every missed day counts. But things were going wrong in Scottish schools long before Covid.

I suspect Gilruth knows where the real blame rests. Back when she was a teacher – at my old school in Edinburgh – she didn’t disagree with her colleagues’ verdict on the overhaul. One of them called it a ‘slow-motion car crash’. Other teachers dubbed it the ‘Curriculum for Excrement’: a verdict that has not been contradicted by the results.

It puts a big focus on coursework, which is far more subjectively judged than exams. Researchers looking into the new system describe a ‘culture of performativity’ among the teachers under pressure to raise attainment. They also found worsening exam performance despite pupils studying a narrower range of subjects: a reform designed to improve results. It seems clear that if the old system was brought back there could be a significant improvement.

Eric Hanushek, a Stanford academic, has drawn a correlation between PISA results and economic prosperity, which he says shows that no investment delivers a greater return than education. But over the past decade of Scottish educational decline, spending per pupil in real terms has risen by 13 per cent. Meanwhile, England’s funding has been reduced slightly but its schools have leapt up the league tables. If devolution were an experiment, the conclusion might well be that it’s hard to find a direct link between spending and pupil attainment, and that teaching methods make a big difference. After almost two decades of ‘progressive’ teaching reform, Scotland is no longer an example to the world, but a lesson in what not to do.

Comments