The acute emotional pain caused by his first wife’s infidelity was of priceless service to Evelyn Waugh as a novelist, says Paul Johnson

Evelyn Waugh died, aged 62, in 1966, and his reputation has risen steadily ever since. His status as the finest English prose-writer of the 20th century is now being marked by an annotated complete edition of his works, sumptuously published by the Oxford University Press. As a prolegomenon, Penguin is issuing another complete edition in hardback, the first eight volumes of which are now available, priced £20 each. They include his life of Rossetti, three travel books, Labels, Remote People and Ninety-two Days, and his first four novels, Decline and Fall, Vile Bodies, Black Mischief and A Handful of Dust. These books, published between 1928 and 1934, cover his emergence as a major novelist.

Waugh’s gifts as a storyteller are now so obvious to us, and fit so well into his overwhelming personality, that it is impossible to think of him as anything else. But he might not have become a novelist at all. He came down from Oxford having acquired expensive tastes in cigars, wine, travel and rich company, and for many years his main concern was how to earn enough to indulge them.

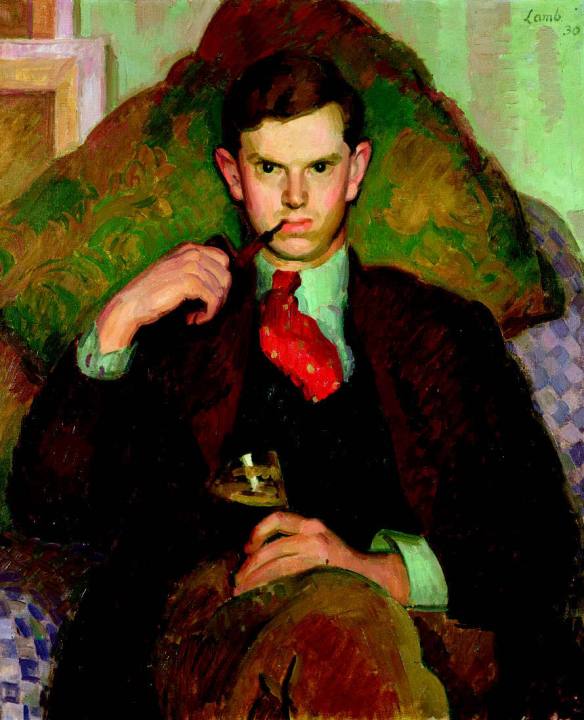

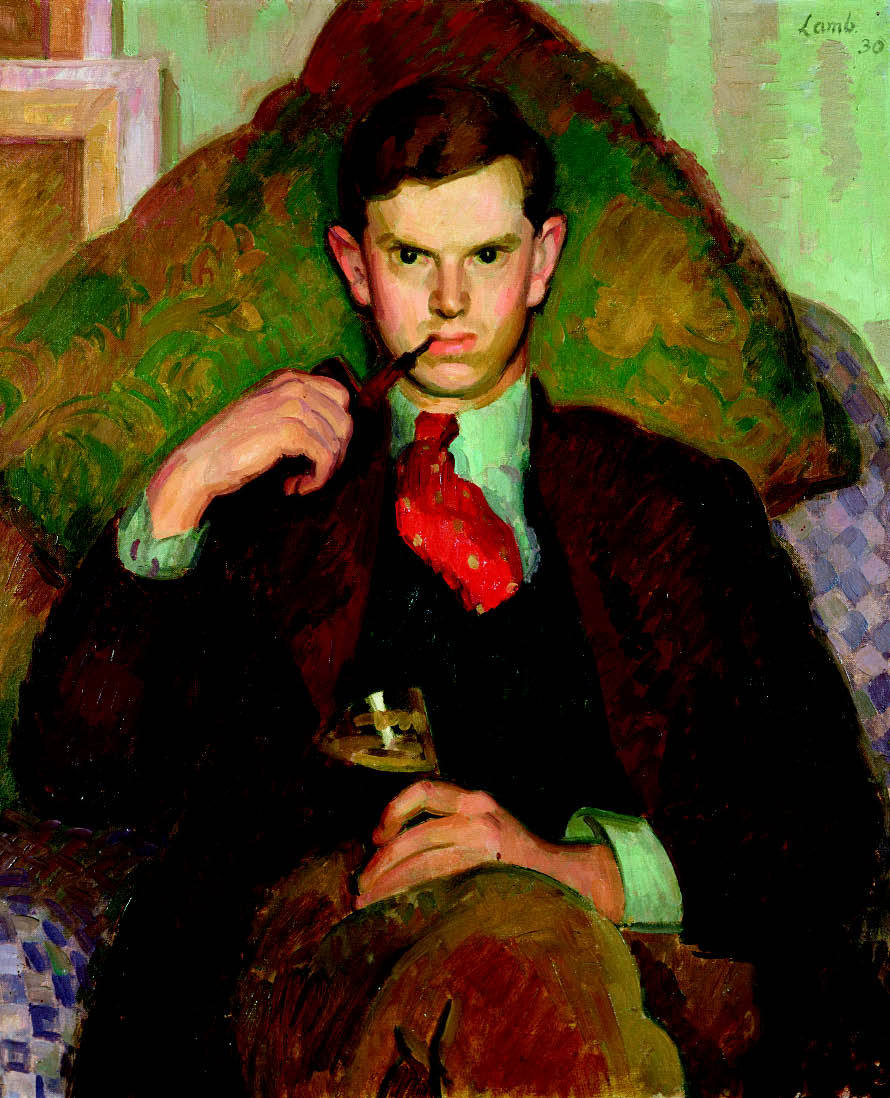

As his father was a publisher and his elder brother an established author of fiction, writing was clearly the family trade. But this might have operated strongly against taking it up, had cash been easily come by in other ways. He was drawn more to the visual arts than to writing, and illustrated several of his earlier books. What he respected was craftsmanship, and his happiest days, he later said, were spent learning to be a carpenter. Indeed the aspect of writing which appealed most to him, all his life, was the choice and manipulation of words, and the carving of sentences and paragraphs.

As things stood, an unqualified young man with a poor degree had little alternative but to take up schoolmastering in one of the private prep schools which then proliferated. This Waugh did for three years, the unhappiest in his life, which included an unsuccessful suicide bid. For someone with his destructive, anarchic and ruthless sense of humour, teaching on the slippery bottom rung of the educational ladder was an opportunity to acquire grisly material for fictional use.

But he did not immediately realise this. Art remained a priority. While still teaching, he printed privately an essay on the Pre- Raphaelite Brotherhood, good enough to attract the notice of the publisher Duckworth, who commissioned him to write a book on the life and work of Rossetti. Waugh later claimed that he got more pleasure from this than any other piece of writing.

It still reads well and may become a key text if, as is quite possible, there is ever an attempt to establish Rossetti as a great European master. What emerges from it is a shadowy, unformulated desire, expressed in hostile gestures towards Roger Fry and other Bloomsbury critics, to overthrow the whole basis of current art criticism and the Modern Art movement. It is quite possible to see Waugh devoting his formidable energies and savage propensities to a lifetime of resisting modernism in the cause of craftsmanship. As it was, Waugh’s tastes were later indulged simply by collecting academic masters like Augustus Egg and abusing Picasso, for Rossetti, though reasonably well received, made little money, and Waugh had now acquired the need for a great deal.

Evelyn Gardner, daughter of the ferocious dowager Lady Burghclere, was an expensive but captivating flirt who had already been engaged to nine men, including a ship’s purser, when her eye fell on Waugh. She played a determining role in his life in a number of ways. She was mad about the telephone and the cinema, and increased his already well-developed interest in these two salient aspects of interwar technology. Smart, unscrupulous, volatile and fickle, she shaped his prototype of the modern, godless devil woman, and helped to propel him directly into the arms of her antitype, Holy Mother Church. She reinforced his taste for Mayfair-Belgravia smart society, which he never lost. And, in the immediate present, his desire to marry her made it essential to earn money fast.

The only way he could do that was to write fiction of a new kind. The result was his first novel, Decline and Fall (1928). The pre-publication history of this brilliant and perverse work was precarious and nail-biting, and it might never have appeared at all, in which case Waugh would have turned his back on novel-writing in fury. It was almost called Facing Facts: A Study in Discouragement and even Picaresque, or the Making of an Englishman. Duckworth were horrified by words, expressions and incidents in its content. Waugh was firmly told he must remove references to incest, fornication, adultery, ‘knocking shops’ and the Welsh propensity to commit bestiality with sheep. The debagging incident which is the opening mechanism of the whole tale was also banned, as was the pederasty of Captain Grimes, the novel’s most important comic character, and his raison d’être. Plus many other things.

So desperate was Waugh that he almost complied and made the cuts, which would have killed the book stone dead. Instead he decided, in another desperate move, to take it to his father’s firm, Chapman & Hall. His father, who had taken some blows from his younger son, would probably have rejected it, and certainly in its uncensored form. Happily, he was away at the time. Even so, the novel was accepted for publication only after a decision of the board carried by one vote. As it was, the novel was a major critical success, led by an enthusiastic review in the Evening Standard by Arnold Bennett, then the most influential critic. What distinguished it was a new economy of words, which enabled the telling of an enormously complicated tale, with a host of characters, in an astonishingly small compass, yet without any impression of hurry or breathlessness.

This was to become the hallmark of Waugh’s prose style, as attractive and infectious in its way as Hemingway’s photo- realism, then the current fashion. Waugh was the first novelist to advance and accelerate his action by the use of phone conversations, and he also adopted the new movie technique of rapid scene-cutting and cross-cutting. Not everyone who enjoyed the book was aware of this deliberate adopting of advanced technology in literary usage, but they knew something quite new was happening, and rejoiced. Waugh intensified, refined and elaborated his new way of telling a tale in his second novel, Vile Bodies (1930), and used the phone/movie devices to enhance the joke content, so that for the first time he pushed into the bestseller category.

This in turn enabled him to sell his services as a travel writer, a recognised category of clever young English writers in the 1930s, the last of whom, Patrick Leigh Fermor, died only last month. Waugh might easily have joined this group but for one insuperable reason. He travelled to ‘get away’, always a compulsion. But none of his travel books reveals any profound interest in the places he saw, the people who inhabited them or the art they produced. Instead, he looked for bizarre characters or events which could provide material for his anarchic humour in fiction. Thus his East African voyage produced the first of his two Ethiopian novels, Black Mischief (1932) and his Guyana trip unearthed his most monstrous comic of all, ‘The Man Who Loved Dickens’.

Waugh hesitated to commit himself to a career as a professional novelist because he already had a terror of running out of material, knowing that he required experiences in his own life to detonate or insinuate plots. He also, I suspect, had another worry. His first two novels were superb exercises in comic heartlessness, for which he had not just a talent but a positive genius. Black Mischief, where the hero helps to eat the heroine at a cannibal feast, reinforced this ima ge. But he knew that no one becomes a great novelist by ruthlessness alone. He must show deep feelings. But how? Waugh cared for nothing.

Then, suddenly, it happened. He experienced agonising emotional pain. Evelyn Gardner again rendered him a priceless service by her almost diabolical treachery. Her cunning adultery and then her flagrant desertion struck Waugh like an earthquake, and showed him that he cared very much indeed. Coinciding as it did with his gradual, then accelerated, immersion in Catholicism, it added a whole new dimension to his fictional appetites.

Almost overnight he became horribly embittered, greedily vengeful and passionately serious. He retained his ruthless anarchism but now it was harnessed to a purpose, to inflict fearful fictional retribution on his former wife. The result was A Handful of Dust, in which Gardner plays both the faithless bitch and her cold-blooded lover. It is a masterpiece of moral horror which makes almost unbearable reading, yet cannot be put down. The scene in which the wife sighs with relief when she learns it is her enchanting son, not her worthless lover, who has been killed, has never been equalled for sheer bitterness. And Waugh ends the book with the blameless hero forced to read Dickens aloud for the rest of his life in his jungle prison.

This outrageous novel was Waugh’s first mature masterpiece, and after it he always knew that something, however dreadful, whether a world war or the onset of madness, would always turn up to give him something to write about. Thus was the writer committed to his creative Via Dolorosa.

Comments