Three weeks ago, I received an SOS from a distressed citizen of Glasgow, urging me to protest against a recently installed display at the Kelvingrove Museum, ‘Glasgow – City of Empire’. Predictably, the exhibition falls over itself to clock every conceivable association between the city and slavery, inviting the visitor to envisage appropriate reparations. Scraping the barrel of shame, it complains of one of Glasgow’s greatest benefactors, William Burrell, that ‘his business partners exploited enslaved Africans’. Enslaved Africans? Burrell was a shipping magnate around 1900, almost 70 years after slavery’s abolition in the British Empire and at least a generation after emancipation in the United States.

As for the city’s world-leading role in the movement to abolish slavery in the early 1800s, and the Scots’ disproportionately high role in the British Empire and its century and a half of anti-slavery endeavour, the Kelvingrove has nothing to say.

Listening to people who haven’t been much heard is a good idea; agreeing with whatever they say is not

So I dispatched an eight-page letter to Kelvingrove’s manager, and a shorter version to the Scottish Times. Replying to the Times, Duncan Dornan, who runs Glasgow’s museums, defended the display on the ground that it was designed through extensive discussions with ‘diverse communities’.

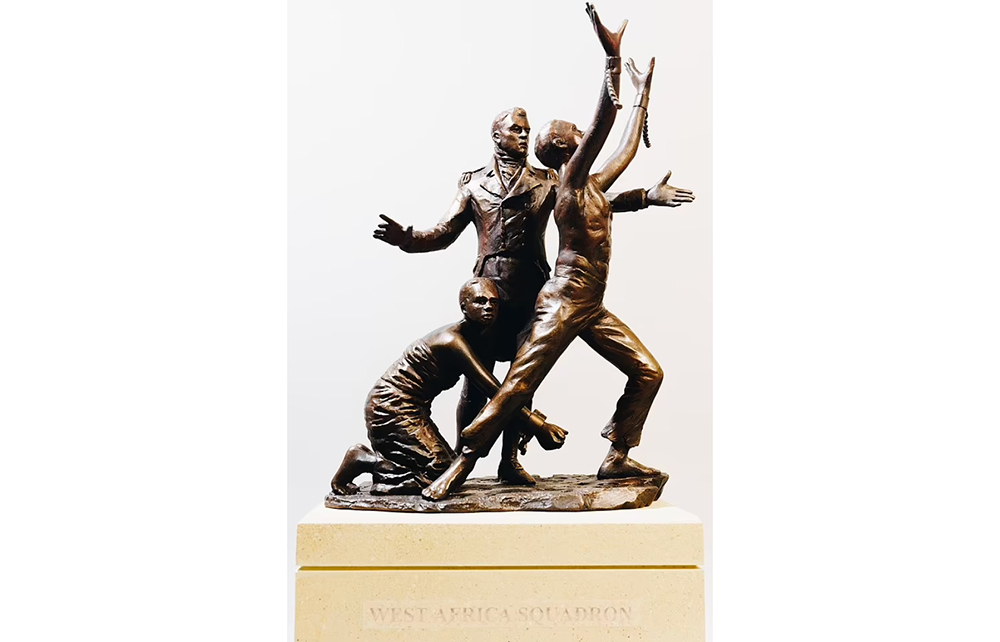

The same week, something similar happened in Portsmouth. A proposal to commemorate the Royal Navy’s role in ending the Atlantic slave trade with a statue on Gunwharf Quays was turned down by a property developer. Why? Because Landsec, the commercial owner of the Quays, had consulted their ‘employee diaspora network’, who considered the statue out of keeping with an ‘inclusive environment’, lacking ‘sensitivity to what is a very emotive topic and dark part of our history as a nation’.

In both cases, organisations at opposite ends of the country had given members of ‘diverse communities’ and a ‘diaspora network’ a veto over the public representation of Britain’s history. The kindest way to understand this runs as follows. Since the voices of ethnic minorities have been marginalised historically, we should listen to them. And since they continue to suffer ill-effects stemming from their ancestors’ enslavement or colonial subjection – perhaps in the form of post-colonial racism – we should defer to them. They now get to have the final word.

One fly in this ointment is empirical evidence that Britain is not generally racist, and that racism may not be the cause of the disadvantages some ethnic minorities suffer. A 2018 report of the European Union Agency for Fundamental Rights found the prevalence of racist harassment perceived by people of African descent was lower in the UK than in any other EU country except Malta. The 2021 report of the UK government’s Commission on Race and Ethnic Disparities, ten of whose 11 commissioners were not white, concluded that contemporary Britain is not structurally racist and disparities between ethnic groups can have a variety of causes.

Another problem is that just because some descendants of slaves identify with their ancestors, feeling deeply that they suffer the continuing effects of enslavement two centuries ago, it doesn’t follow that they really do. My forebears include 17th-centuryCovenanters, who were forced to worship their Presbyterian God in secret, fled defeated from battlefields, and were hunted in the hills of southern Scotland by government troops. Is their misery mine? Not obviously.

It might be that Caribbean Britons do suffer material disadvantages because of their ancestors’ enslavement. But that has to be demonstrated, not assumed. Much has intervened in the past 200 years to eradicate historic ill-effects. Indeed, there is evidence that some whose ancestors were transported from West Africa to the West Indies are now considerably better off than many whose ancestors stayed behind. According to World Bank data, in 2020, life expectancy in post-slavery Barbados was 24 years higher than in post-enslaving Nigeria; literacy in Barbados (in 2014) was almost 40 per cent higher than in Nigeria (in 2018); and gross national income per capita was 482 per cent higher.

A further reason not to take at face value the voices of those purporting to speak for marginalised minorities is that their members don’t all think the same thing. Soon after my name was plastered all over the press in the wake of the campaign to shut down my ‘Ethics and Empire’ project in 2017, I received an email from an ethnically Indian acquaintance, who was a medical consultant in Leicester. He told me that his grandfather had been in the unarmed crowd in Amritsar upon which General Dyer had infamously ordered his troops to fire in April 1919. ‘But,’ wrote Raj, ‘I agree with you: the British Empire contained good as well as bad.’

Listening to people who haven’t been much heard is a good idea; agreeing with whatever they say is not. Take Canada. In May 2021 claims were made in Kamloops, British Columbia that ground-penetrating radar had discovered the remains of 215 ‘missing children’ in land associated with an Indian Residential School. Eyeing the power that victimhood bestows, ‘First Nations’ politicians quickly sexed the story up into one of ‘mass graves’, with all its connotation of murderous atrocity. Led by the New York Times, the mainstream media then broadcast the lurid tale. Because the Kamloops school had been run by a Roman Catholic order, some zealous citizens took to burning Catholic churches, at least 83 of which have since been vandalised or razed to the ground.

Yet, three years later, not a single set of remains of a murdered Indian child has been found in Canada. And judging by the evidence collected by C.P. Champion and Tom Flanagan in their bestselling 2023 book, Grave Error: How the Media Misled Us (and the Truth about the Residential Schools), it now seems that the Kamloops story and the similar ones that followed it are politically motivated myths.

Comments