In the America of the 1950s, one question dominated foreign policy: ‘Who lost China?’ The Communist victory in the Chinese Civil War and the defeat of America’s ally, the Kuomintang regime, provoked agonised debate about the principles that should guide statecraft – the balance between containment and pushback, the relative importance of winning hearts and minds or prevailing by strength of arms.

The question that we might ask today is: ‘Who lost Ukraine?’ Of course, the war between Kyiv and Moscow is not over. Ukraine’s army continues to fight with a tenacious courage that is inspiring. Volodymyr Zelensky’s diplomatic efforts to maximise support for resistance are unflagging. But all the winds blowing now are ominous for Ukraine.

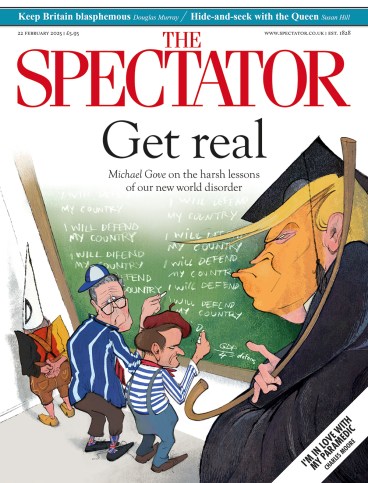

The negotiations between US and Russian officials which started in Saudi Arabia this week – with Ukraine not just sidelined but shunned – seemed to portend a division of territory to suit Vladimir Putin, not Ukraine’s people. The demand from Team Trump that the US get its hands on mineral revenues from Ukraine in return for military and financial support seems grimly transactional rather than mutually beneficial. And the US President’s claims that Ukraine could have resolved this conflict far earlier, and thus bears responsibility for its people’s suffering, are chilling.

Faced with Trump’s actions, European leaders, not surprisingly, have responded with outrage. They feel they have contributed as much to the war effort between them as the US has done. They are naturally fearful, too, that they have the most to lose from a poor settlement with Putin because they live on Russia’s doorstep.

Those fears are not irrational. Any deal which allows Putin to end the war claiming victory will only embolden him, possibly putting other countries at risk of destabilisation at best, incursion at worst. Putin has made it quite clear that he considers the break-up of the Russian empire after the end of communism in the 1990s to be an epochal tragedy. The Baltic states – formerly Soviet territory and now Nato stalwarts – are particularly vulnerable. So long as Russia was exhausting its military reserves in Ukraine, it could not turn its attention elsewhere. When the fighting ends and Russian forces are given the chance to regain their strength, Moscow’s gaze will be cast covetously elsewhere.

But while Europe’s leaders might fear Trump’s motives and Putin’s ambitions, they cannot escape responsibility for where we are now. The support they, and the US, have provided since 2022 (it is roughly half each in monetary value, if you include all European contributions) has managed to keep Ukraine on the battlefield, but has fallen well short of what would be required for it to prevail over its much larger enemy. Armaments, reinforcements, air power and missiles have been supplied slowly and grudgingly by European nations who have claimed to will Ukraine’s victory, but have not guaranteed the means.

The nations of Europe offered a future to Ukrainians they were

not prepared to underwrite

This infirmity of purpose towards the defence of Ukraine’s sovereignty predates the 2022 invasion. Putin got away with the annexation of Crimea in 2014 with hardly a whimper from Europe. Germany signed the contract for the Nord Stream 2 pipeline after that outrage. When Putin lined up his tanks on the Ukrainian border in late 2021, Germany continued to build dependence on Russian energy by closing down its own nuclear power stations. At this point, Boris Johnson’s government quickly reacted with the gift of arms to Ukraine – yet the first flights carrying supplies had to be flown around Germany because Olaf Scholz did not want to be involved.

Belatedly, Germany became a significant donor of arms to Ukraine, but the damage had already been done. For decades, Europe was happy to shield beneath America’s military umbrella, preferring to spend revenues on social programmes. It was not until the first Trump presidency that it began to sink in that the US would not put up with this arrangement forever. Trump was lambasted for complaining, at the 2018 Nato summit, that the US ‘loses big’ out of Nato membership. The then Nato secretary-general, Jens Stoltenberg, called his comments ‘unacceptable’ – the same language used by European leaders to describe the speech by Vice-President J.D. Vance to the Munich Security Conference last week. Yet by 2018, only three Nato members other than the US were meeting the target of spending 2 per cent of GDP on defence – which was supposed to be a condition of Nato membership.

So when it comes to asking who lost Ukraine, it is not enough to lament Trump’s propitiation of Putin or America’s retreat from its responsibility as a global superpower. The countries which held out the promise to Ukraine of EU and Nato membership – the nations of Europe – offered a future to Ukrainians they were not prepared to underwrite with an iron will.

The lesson for all of us is that democracy does not secure victory by finely worded communiqués and European Council resolutions, but by a resolution on the battlefield Europe has been too scared to show.

Comments