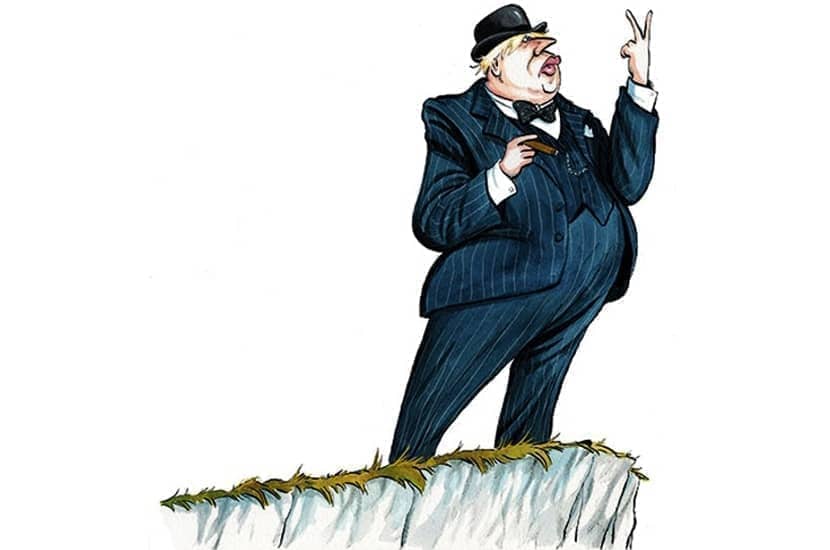

Although it’s deeply unfashionable to say so – particularly if you work in the media – I like Boris Johnson tremendously. I’m sure I’m not alone. I like him chiefly because he’s unfailingly funny. Every time I hear him on the radio or see him on the television, he says or does something that brightens up my day. Most recently it was his comments after President Macron’s hissy fit over AUKUS – ‘donnez-moi un break’ – but he’s been doing it for years.

I believe there are two types of people in the world: people who are funny and people who are not. It goes without saying people who are not funny are often deeply mistrustful of those who are. I only trust people who are funny. I don’t think this is a particularly unusual method of appraising people. In fact, I think it’s a fairly standard British outlook on life.

But Boris’s ability to make people laugh is used against him endlessly by his critics. His jokes, they never tire of saying, denote lack of seriousness – they’re evidence that to him it’s all just a game, or that he’s conning us. Only last week, my colleague Nick Cohen was lamenting in these pages how Boris’s supporters ‘don’t mind being fooled by the PM, because he lets them in on the gag.’ He went on to ask: ‘how can the country be so stupid?’

But the opposite is surely closer to the truth. To my mind, Boris’s jokes demonstrate he cares profoundly – that he’s thought sufficiently deeply about what he is saying to be able to offer perspective that is both fresh and funny, and also that he possesses enough respect for his audience to have framed his argument in a way that will bring them with him most effectively. It would be much, much, easier not to be funny. The humour, I think, signifies a type of honesty.

To my mind, Boris’s jokes demonstrate he cares profoundly

Equally true: every politician in the land would give an arm to be able to speak so entertainingly.

I also like Boris because problems seem consistently to evanesce in front of him. This strikes me as a useful superpower for the leader of the nation. Always his critics make light of his considerable achievements – most notably in winning the Conservative party’s biggest parliamentary majority since 1987, but also in delivering Brexit and becoming mayor of London twice – by saying he was dealt a good hand or that he was plain lucky. But at some point it must be acknowledged a very clear trend has emerged: the man simply doesn’t lose.

Boris also seems kind. No doubt he’s as ambitious as the rest of the reptiles in Westminster, but he doesn’t seem as utterly ruthless. He has repeatedly demonstrated highly laudable magnanimity by not lashing out at those who have done him most dirty – most notably Michael Gove and Dominic Cummings.

Personal attacks have never been his style. Despite his clear popularity with voters, he’s consistently treated with astonishing viciousness in the press – perhaps because he is also a journalist – but he has never once responded in kind. The closest he got to retaliating was when he lamented to a classroom of children that ‘when you’re a journalist, the trouble is you find yourself always abusing or attacking people… maybe sometimes you feel a bit guilty about that because you haven’t put yourself in the place of the person you’re attacking.’ But even that was quite a funny thing to do.

Has Boris had a good pandemic? No. But also yes. He’s maintained his party’s healthy poll lead over Labour throughout the crisis, and his personal popularity ratings have also held up. This is because the public has recognised he didn’t enjoy locking us all up for weeks on end – indeed, that curtailing our liberties went against everything for which he instinctively stands – and forgiven him for it.

On top of that, the furlough scheme has kept most people afloat, and the vaccine rollout has by any measure been a shimmering success – particularly when compared to the EU’s, which for the first half of this year seemed not unlike a monkey’s attempt to make love to a football. And now our economy grows faster than that of any other G7 nation.

Yes, Boris’s love life is obviously a car crash, but then so is a very substantial proportion of the electorate’s. We just don’t care, not least because he hasn’t been hypocritically sanctimonious on this, or any other subject. It only makes him seem more human. If the rumours are true that he’s terrified of his wife, all the better. Most men are.

The only point I can think of that has meaningfully undermined Boris over the course of his more than two decades in politics is the tragic case of Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe – for which he must undeniably accept some culpability. It was his mistake in 2017, when he said in parliament she was working in Iran, and not, as she said, on holiday, that was used by her captors to worsen her plight. One suspects he regrets that.

It will be interesting now to see if he can pull off yet another miracle by turning back the ominously rising tide of inflation that threatens to drown the economy. I don’t see how it will be possible to do so, but that doesn’t mean I don’t think he’ll manage it somehow.

I therefore predict that Boris will be in power for a long time – long enough for his detractors to admit he isn’t merely lucky. Eccentric, optimistic and fundamentally humane, he personifies the very best British ideals, and that’s why the public loves him. Who knows, maybe being nice about him in print will come back into fashion?

Comments