I have come late to Nora Ephron — a little too late for her, anyway, as she died in 2012. Indeed, it was just after she breathed her last that I read her only novel, Heartburn, a copy of which had been pressed on me by a writer friend with a mad glint in her eye. It is that sort of book, and I now press copies on other friends with the same mad glint. A brutal dissection of Ephron’s disastrous marriage to the Watergate journalist Carl Bernstein, it’s also a brilliantly sustained piece of comic writing, as good as anything you’ll find outside Wodehouse. Nigella Lawson loves it, as well she might.

Why no other novels? Maybe Nora never again felt the need in quite the same way, or maybe she was too busy writing everything else. A prolific journalist in her youth, she moved on to screenplays with Silkwood, a screen version of Heartburn and, sublimely, When Harry Met Sally. The vast profitability of the latter gave her the chance to direct her own scripts: Sleepless in Seattle, You’ve Got Mail, Julie & Julia. In her final years she returned to prose, with two glorious books of essays on ageing, both bestsellers. These were just the successes. As with any writer, the failures took up even more time.

The Most of Nora Ephron, then, is her posthumous greatest hits album, lovingly compiled by her longstanding editor Robert Gottlieb. There’s a dash of Heartburn here, the stream-of-consciousness plot splurge that opens the book; a scene or two from When Harry Met Sally; and a few of the best of the later essays. Unless you’re a Nora nerd, though, much of this material will be unfamiliar. There are good, robust, strikingly confident examples of her early journalism, the complete text of her late play Lucky Guy (produced on Broadway after her death), and a decent smattering of blogs for the Huffington Post.

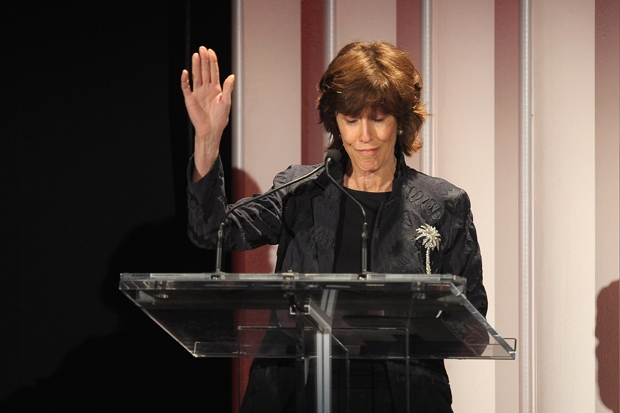

Some of the journalism, one has to say, has dated to the point of inconsequentiality. It’s hard to feel strongly about the factionalism and rivalries among American feminists in 1972, or New York food writers in 1976. But however dry the subject, her warmth of tone and sharpness of observation never fail her. ‘Everything is copy,’ her screenwriter mother once told her. For Nora, though, journalistic ruthlessness is always tempered by a fundamental decency, a kindness if you like. Tough shell, soft heart. Most of her films have happy endings. Life tends not to, but she’s not going to worry about that right now. Age and experience do not blunt her perception, though. One previously unpublished piece is a commencement address she gave in 1996 to new graduates of her old college (Wellesley):

The women’s movement has made a huge difference… particularly for women like you. There are women doctors and women lawyers. There are anchorwomen, although most of them are blond. But at the same time, the pay differential between men and women has barely changed. In my business — the movie business — there are many more women directors, but it’s just as hard to make movies about women as it ever was, and look at the parts the Oscar-nominated actresses played this year: hooker, hooker, hooker, hooker, and nun.

Curiously, Ephron is known as a writer of snappy one-liners, but it’s not really her strength. As she explains, the best known line in When Harry Met Sally wasn’t even hers. Meg Ryan fakes an orgasm in a restaurant, and when she’s done, a woman at a neighbouring table leans over and says, ‘I’ll have what she’s having.’ It was Ryan’s suggestion that she fake the orgasm. The actual line was Billy Crystal’s. Ephron’s contribution was to find it funny and put it in the script.

India Knight, in a sweet introduction that tries not to gush and fails hopelessly, suggests that, although she was 71 when she died, Ephron clearly had more to offer. It’s hard to disagree. Some of the HuffPo blogs are tiny masterpieces of comic construction, and even towards the end she never wrote as though the end was nigh. Maybe this is the great consolation of the humorous life: that even the prospect of imminent oblivion is quite amusing. If that’s true, when the day comes, I’ll have what she was having.

Available from the Spectator Bookshop, £16.50 Tel: 08430 600033

Comments