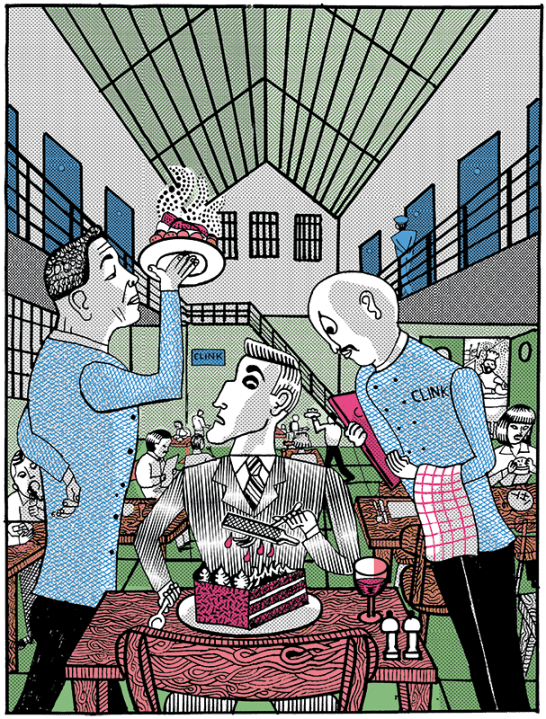

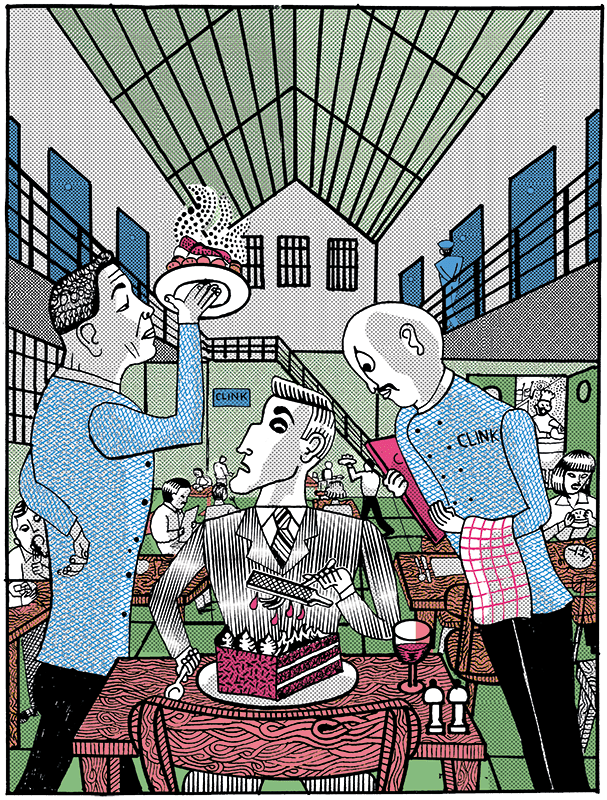

For 15 years The Clink charity has run commercial restaurants in prisons, training inmates to cook and teaching them front-of-house service. It is a vital way of giving offenders a second chance. But many of its operations have been forced to close due to the folly of the Ministry of Justice (MoJ).

At Styal women’s prison in Wilmslow, Cheshire, The Clink restaurant, which has been running for ten years, cannot continue to operate. Despite plenty of interest from inmates, recent changes to the eligibility criteria have drastically reduced the number of women permitted to work there. ‘Sometimes we are trying to run it with five, possibly only three, women,’ explains the manager. ‘It’s just not possible.’

The MoJ thought it would be hard to justify prisoners being filmed singing, dancing – better to keep them bored

The first Clink restaurant opened in HMP High Down in 2009, founded by a charismatic chef called Al Crisci. Since then, the charity has had restaurants in three other prisons – Cardiff, Brixton and Styal – staffed mainly by inmates and open to the public. It also runs horticulture projects at HMP Send and Erlestoke, some kitchen training, a catering arm employing ex-offenders and an events business training women at HMP Downview, which serves London venues such as the Guildhall, the Cutty Sark and the Science Museum. A thriving commercial bakery in Brixton sells goods to the public, although for some daft reason it is not allowed to supply the prison.

I highlight The Clink because it is an excellent example of the vital role charities play in prison rehabilitation. One might think that prisons would do everything they could to stop inmates reoffending. And that, to this end, the government would insist that prisons were education centres so those who arrive barely able to read would leave qualified to get a job and stay out of prison.

But talk to any charity involved in prisons (and all the imaginative and effective work with prisoners appears to be done by charities, not by the Prison Service) and you hear the same thing: increasing resistance to charity involvement.

The problem is partly due to funding and resources. Prisoners will be told, for instance, that they are not allowed to come to a training session because there is no prison officer available to escort them from their cells. Others will be denied a session for some undisclosed or arbitrary reason. The charities generally raise most of the money they need, but the Prison Service sometimes funds the activity. I once attended an awards dinner in Scotland, where a highly successful charity, which arranged jobs for women offenders on day release, won an award. I asked the CEO why she looked so glum. That morning, she said, she had received a letter from the same prisons minister who had just handed her the trophy, informing her that there would be no funding next year. The charity would have to close.

Any charity working in a prison must build a good relationship with the prison staff if they are to succeed. But often the problem is not with the officers, most of whom want to support education in prisons. The fundamental issue is the attitude within the MoJ and a fear of being criticised by the press for being nice to criminals. To make matters worse, restrictions implemented during the pandemic are mostly still in place, with prisons ever more unable or unwilling to support many educational projects.

I have experienced first-hand the resistance to charity work within prisons. A few years ago, I was keen to make a documentary about what can happen if a governor with a smidge of imagination is in charge. The documentary was to be entirely positive. We hear all the time about how bad conditions are in jails, with understaffing, buildings not fit for purpose, union intransigence and poor management. Yet, in spite of these problems, there are truly inspiring initiatives – and I wanted to highlight some of them.

We wanted to follow budding chefs in The Clink restaurants, look at the effects (on behaviour and attitude, on life after prison, on reoffending etc) of working in vegetable gardens, of keeping hens or bees, or doing embroidery. The charity Fine Cell Work, for example, teaches prisoners – mostly men with a history of violent crime – to do tapestry in their cells. They learn to make cushion covers and quilts for sale to high-end shops, while increasing their earnings, which they then receive on leaving prison. If they are lifers, their pay goes to their families.

Then there are the Koestler Awards for inmates’ art and the Pimlico Trust, which mixes inmates and professionals in staging theatrical and musical workshops in prisons. The Prisoners’ Education Trust helps a few lucky inmates to learn to read, sit exams and take degrees, while the charity Give a Book organises reading groups in jails. Only Connect works to rehabilitate prisoners before release.

When we mooted the idea with our contacts in the Prison Service, they were enthusiastic. Gradually we gathered support, from the charities to the prison officers they work with, to the governors and even the MoJ. Finally, we were told we would need clearance from the secretary of state. So I wrote to make the case that the way to tackle the public’s belief that prisoners are mollycoddled is to show viewers that equipping prisoners for work helps prevent reoffending. I got a prompt reply, in favour of the idea, but informing me that the matter was to be decided by the MoJ’s public relations department. They then vetoed it, without explanation. I suspect they thought it would be hard to justify prisoners being filmed singing, dancing, farming or working in a restaurant – far easier to keep them bored and demotivated.

Imagine leaving prison with a plastic bag containing the possessions you brought with you and a discharge grant of £82. Unless you are lucky, or your prison has been halfway decent, or a charity has been helping you, or you have a supportive family, no one meets you at the gate. You might have nowhere to live and you certainly don’t have a job. The money is quickly spent in the nearest pub and all your resolutions about starting a new life disappear. The only way you know how to make money is by stealing it. No wonder three-quarters of ex-prisoners reoffend within the first nine years of release. No chance of freeing up prison space with that record.

A night in a cell costs as much as one in an average London hotel so there is a clear economic case, let alone a philanthropic one, for helping inmates learn new skills so they can stay out of prison. Last year The Clink placed 184 prisoners in jobs on their release. The charity’s at-the-gate support and resettlement programme enabled these offenders to reintegrate into society. They helped with housing, medical needs, family connections, further education and, of course, consistent employment. The tragedy is that those prisoners are the lucky few.

Comments