It has been my privilege over the past two weeks to sing in the chorus of the Orchestra of the Age of Enlightenment under conductor Simon Rattle and director Peter Sellars in a staged production of J.S. Bach’s St John Passion. The experience has been life changing for some of my colleagues; it has certainly been unique. Dressed in black casual clothing, we spend much of the performance sauntering around the stage making abstract gestures intended to highlight certain words and distill the myriad emotions found in the music. Some find this effective; others find it silly.

Sellars’s forte as a director is his ability to communicate to his performers the unbridled emotion that he wants us to give to the performance, exhibiting for us rage, sadness, pain, calm or gratitude in his direction one moment, and then resuming his always cheerful manner in the next. He is endearing, amiable and sincere, and his commitment to the emotion and drama of whatever work he is directing is total. Rattle, for his part, strives to bring out the full spectrum of available nuance and colour in his performers, taking the music apart layer by layer and then reconstituting it, every phrase charged with a fresh intention. The two men are often at odds about what they want, but the process is a mutual exploration and the result is usually something they both appear to find immensely satisfying.

Yet, abstract minimalism aside, I consider their approach to be deeply flawed. I have spent the past fortnight observing, listening, participating, and trying to figure out why.

Bach’s St John Passion is undoubtedly one of the greatest works of art. It’s an emotional and intense dramatic work, certainly. But it’s not only that. What Sellars’s and Rattle’s treatment has attempted to do is give a very intricate and comprehensive analysis only to this dramatic and emotional aspect.

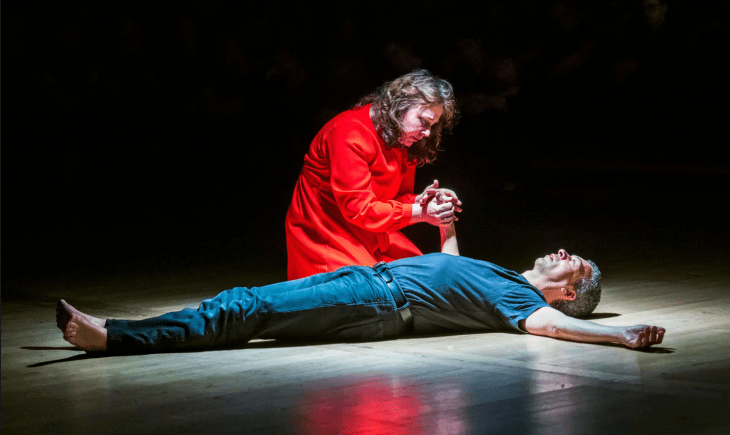

In rehearsals Sellars provided some profound insights on the Gospel of John and the significance of the suffering of Christ. But his staging, especially during the arias, largely ignores the text, seemingly in order to explore some other emotion or fancy that he had already decided upon, whether or not it belongs. To give two examples, Sellars presents the soprano and alto soloists as Mary, the mother of Jesus, and Mary Magdalene, respectively. He portrays the two women offering Jesus comfort in his suffering, each in her respective way. Mary, his mother, sings about following Jesus always with joyful steps in the aria ‘Ich folge dir gleichfalls’. This aria is meant to be a prayer reflecting Peter’s earnest discipleship immediately before he denies Christ – it makes no sense to have Mary sing it. Mary Magdalene (Jesus’s girlfriend, obviously) sings the aria ‘Von den Stricken’ – about Christ’s bondage paradoxically freeing us from the bonds of our own sin – while she and her BF share The Last Shag. Perhaps in future revivals they’ll cast a countertenor – a homosexual Jesus and a transgender Mary Maggers in one move. (The bondage theme could have come in handy here – at least that would bear the slightest connection to text.)

Offending Christians is nothing new. The stale, played-out fancy that Jesus had a sexual relationship with Mary Magdalene was a controversial titillation when Nikos Kazantzakis wrote The Last Temptation of Christ in 1955, and more recently Dan Brown’s The Da Vinci Code revisited the idea. Jesus was portrayed as a homosexual twenty years ago in Terrence McNally’s play Corpus Christi. And of course ‘Piss Christ’ courageously explored the hitherto neglected artistic possibilities of whatever putting a treasured religious symbol in one’s own urine accomplishes. But these are all the original products of modern imaginations. Applying such an imaginative interpretation to a pre-existing work of art is not creating something new, but rather misconstruing something definitive that’s already been said, and said well.

Despite the abundant drama and emotion, the St John Passion is not primarily a dramatic/emotional work; it’s not a piece of theatre. Bach didn’t simply start with a story and thence attempt to bring it to life with music. He started with Lutheran theology (albeit with a somewhat Catholic flavour) and the framework of the liturgy in which the passion narrative was presented. His music expresses the inarticulable truths that accompany the story, the arias and chorales serving as theological commentary examining the relationship between fallen man and his redeemer. It is primarily a theological work. To interpret a work of such symbolic genius in purely emotional terms necessitates divorcing the work from its central purpose, and presenting an exploration of only the periphery of the art. Whatever drama and emotion there may be, which so many, Sellars and Rattle included, have found irresistible, these are byproducts issuing from the solid theology that grounds the piece. Cutting it off from that foundation lessens the impact, resulting in mere sentimentalism or nonsense. This is the difference between great art and soap opera.

But it doesn’t stop there. The drama and emotion are but a fragment of the whole, and however acute Peter Sellars’s analysis of that fragment may be, if the remainder is missing it inevitably will be substituted with something else from the director’s imagination, such as the examples given above. And if that is the case, it’s no longer a presentation of Bach’s composition; it merely uses Bach’s score as the soundtrack for something else. That’s the most charitable assessment I can give of this production – at minimum it’s a misuse of the music.

Under the influence of deconstruction, the disintegration that has characterised the evolution of modern art is now turning its aim backwards to devour the ordered art of the past, and to obscure all intended meaning from it. And the consequence can only be an aimless postmodern superficial treatment of an ordered, concrete, profound work of art.

True art is cognitive. It attempts to say something truthful and objective that cannot be said any other way. If modern artists want to create random nonsense that means whatever anyone wants it to mean, they can. But Bach was certainly not trying to do that with the St John Passion. He gave the world a cognitive-theological masterpiece, an emphatic statement, that also happens to be dramatic, emotional and exquisitely beautiful. I don’t know if there were any traditional Lutherans involved in this production, but that doesn’t matter. There were hardly any Germans in our cast; that’s why we had a language coach. Why not a theologian? Why the effort to get the details perfect, but no attention paid to the cognitive substance? Sellars’s treatment skims the surface, while ignoring, denying and contradicting Bach’s actual statement, and thereby misconstrues Bach’s purpose and performs an iconoclastic exercise.

I’ve seen staged oratorios far more egregious than this. There are poignant and effective scenes in this production with splendid performances that allow Bach’s genius to shine through, despite the misguided interpretation. What disheartens me most is that this interpretation isn’t some fringe artistic community trying to be provocative and rebellious, but the top names in the classical world presenting the greatest music to the world’s most sophisticated audience. It’s an injustice – Bach is being silenced even as we claim to celebrate his music.

Can a staged Bach Passion work at all? I’m not sure. If it can, it must seek to serve Bach’s intention. But it may be the case that the further we move away from a liturgical treatment (and the scarcity of Lutheran churches with a resident full orchestra and professional choir makes this unavoidable), the less contemplative the passion becomes, and the greater the danger that the artistic merit of the piece, the symbolic heart, will be lost, if not ripped out. It then becomes all too easy to see it as a piece of entertainment, inadequate for a modern audience because it lacks a visual element. Jonathan Miller’s staging of the St Matthew Passion two decades ago worked. I would still argue that it detracted as much as it enhanced, but at least Miller was conscious not to compromise the integrity of Bach’s statement. Miller is an outspoken lifelong atheist, but he respected Bach enough to let Bach speak.

It may appear to be bad form for me to criticise a performance that I’m a part of, but I sincerely believe that the truth Bach tried to convey in the St John Passion has been obscured in this production and as a result I feel compelled to tell the truth about it. And the truth, incidentally, is something that St John was rather keen on.

Andrew Mahon is a Canadian-British writer and classical bass-baritone based in London

Comments