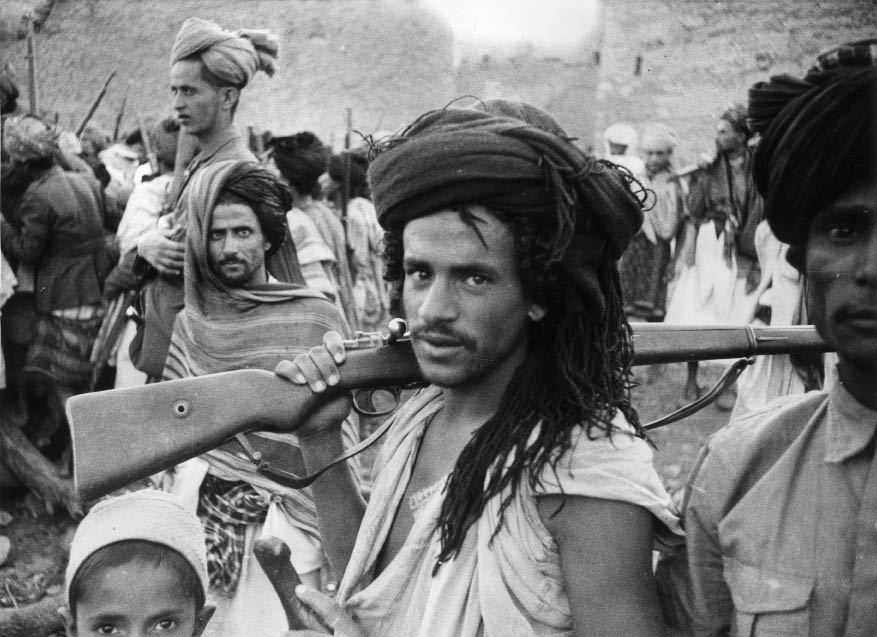

Philip Hensher recounts how a handful of British mercenaries in the 1960s, headed by the Buchanesque Jim Johnson (pictured above), trained a rag-tag force of Yemeni tribesmen to defeat the full might of the Egyptian army in a conflict that Nasser later referred to as ‘my Vietnam’

‘Enormous fun and a tremendous adventure,’ one of the participants called it afterwards, voicing the sentiments of every British soldier running amok since the beginning of time. Probably there were soldiers under Boadicea who said exactly the same thing. This little known story from the very end of the imperial adventure is redolent of cheek, bravado and the undertaking of a challenge for no other reason than thinking ‘Why the heck not?’ It is almost incredible that it took place well within living memory.

Although Aden had been a British crown colony since 1838, Yemen in the early 1960s was pretty well terra incognita for the western world. It was known to the Romans as Arabia Felix. It had been ruled by the same line of priest-kings for eight centuries. The country was closed to foreigners, and outside a very few urban areas, there was no infrastructure whatsoever. Most of the population had never seen a white man. (When the heroes of this story turned up in rural areas, the locals took to rolling up their trousers without invitation to discover whether they were the same strange colour all over.)

The foreigners who did live there endured a peculiar, Waughish existence of absurdity and constraint. If Ronald Bailey, until 1962 the British Consul in Taiz (the country’s second city) wanted to go for a walk, he first had to obtain permission from the Imam, which could take two weeks to arrive:

If permission was eventually granted, he was obliged to perambulate carrying an open umbrella, to demonstrate that he was a figure of importance, so that people would treat him with respect.

Tribesmen in the hills were in the habit of dressing themselves in anything that came to hand whenever the temperature dropped, including, according to one report, ‘a woman’s thin black evening coat with a tattered fur collar … a relic of the Gay Twenties.’ Some of them had four thumbs, through a genetic quirk. This astonishing country was suddenly dragged into the 20th century by the unwelcome attentions of that undeniably modern figure, Egypt’s General Nasser.

In pursuit of his dream of a united Arab world, Nasser saw a Yemen under his control as the soft underbelly through which he could proceed effortlessly up through Saudi Arabia and on to Jerusalem. He first wooed the alcoholic, fat, drug-addicted son of the Imam, promising Crown Prince al-Badr 25,000 Egyptian pounds and two cases of pistols if he would kill his father. (Drug- addiction was taken for granted in Yemen, and this book includes a memorable photograph of an elderly gentleman chewing qat, the Yemeni narcotic, quite clearly out of his tree.) When a telegram arrived ordering the prince to carry out the deed, al-Badr broke down and confessed everything. Strangely enough, his father forgave him.

But shortly afterwards, to everyone’s surprise, the Imam — himself grotesquely obese — died of natural causes and was succeeded by his would-be assassin. By this time Nasser had had enough. In a palace coup, a puppet of Nasser’s, Abdullah al- Sallal (until fairly recently a street charcoal-seller) took charge, as Egyptian battleships steamed towards Hodeidah, Yemen’s main port. In time-honoured fashion, the new Imam took to the hills.

Enter the British. With Suez fresh in everyone’s mind, and the larger Cold War implications involved in Nasser’s grandiose gestures, there was no great appetite in Britain for a Yemeni adventure. It was all too clearly bound to end in humiliation. Still, there were plenty of people around who thought that Nasser could usefully be stalled. These included Alec Douglas-Home and Julian Amery, as well as members of Mossad. Who was to do the job? Colonel David Stirling ‘arranged (with the connivance of Home and Amery) for Billy McLean to meet Brian Franks (then Colonel Commandant of the SAS) at White’s Club.’

Franks knew a man called Jim Johnson.There have been more likely masterminds of insurgency — Johnson at this time was an underwriter at Lloyd’s — but Franks must have realised that he had his man as soon as he explained that the Royalists in the hills were being attacked by Russian aircraft based in Sana’a:

‘Would you like to go in and burn all these aeroplanes?’ he suggested. ‘Well, yes,’ Jim replied nonchalantly. ‘I’ve nothing particular to do in the next few days. I might as well have a go.’

This Buchanesque figure was quickly supplied with a cheque for £5,000, which he cashed at the Hyde Park Hotel (‘What do you need all this money for?’ ‘My daughter’s getting married.’) and set about acquiring an office in London and some mercenaries, under the strictest conditions of official deniability. Not only was it deniable; those people in the Government who had been aware of the project believed it had been cancelled. After the political explosion of the Profumo affair, Duncan Sandys, the Colonial Secretary, had telephoned David Stirling to call the whole thing off. Sandys, remembered by posterity chiefly as the prime candidate for the ‘headless man’ in the polaroids in the Argyll divorce case, was subsequently described as ‘that shit’ by Johnson.

The campaign went ahead. The potential implications of the war between the Royalists and the Republicans were global in scope. But the fascination of this intricate story lies in the gamy flavour of the characters who brought Nasser’s substantial forces to their knees. Previously, ‘the Yemenis’ normal form of attack was to rush forward, barefoot and screaming, brandishing their jambiyas or firing rifles (if they had any)’. With only a few dozen mercenaries getting the Royalist forces up to scratch, the episode became Nasser’s very own Vietnam, a source of constant humiliation and pain.

Among the dramatis personae was a Canadian dealer in postage stamps calling himself Brigadier General Abdurrahman Bruce Alphonso de Bourbon-Condé; an inspector for the Good Food Guide turned guerrilla; and an airman who later in life took a great interest in developing a medieval siege engine ‘with which he managed to throw a dead sow 340 yards’. We meet various London ‘Q’ types, used to showing visitors who had ‘brought some equipment’ into cellars stuffed with submachine guns; one man got a frightful shock since, it turned out, he was actually a vacuum-cleaner salesman.

And there is Jim Johnson himself, who only visited Yemen once, but who was clearly one of those up-for-anything types who stuff the pages of Buchan, Sapper and Dornford Yates. Duff Hart-Davis has taken over the writing of this book from Jim Johnson’s second-in-command, Tony Boyle, who was working from Johnson’s archive; both men died before the work was completed.

He has done his extraordinary subject justice. Why did any of them get involved with the project? Well, the pay was good, but that is exactly the sort of thing men say to cover their enjoyment and excitement. The fact of the matter is that it was a terrific adventure, the sort which is supposed to have come to a definitive end with the end of the Empire.

Comments