The Rosetta Stone is said to be the most visited object in the British Museum. By and large the most popular, most beautiful or most impressive objects are found at the top of the shopping list of those who want to send objects back to their place of origin. Yet here is a piece of debris that, if installed in the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza, would look as out of place as a dirty pair of trainers in the Athenaeum. This, after all is (or rather will be, after endless delays in its opening) the final resting place of Tutankhamun, a museum rich in gold and lapis lazuli lying in the shadow of the Great Sphinx and the three massive pyramids built by a much earlier dynasty of Pharaohs. Treasures galore, then, a collection of ancient Egyptian art works only rivalled by the British Museum, the Louvre and the Egyptian Museum in Turin.

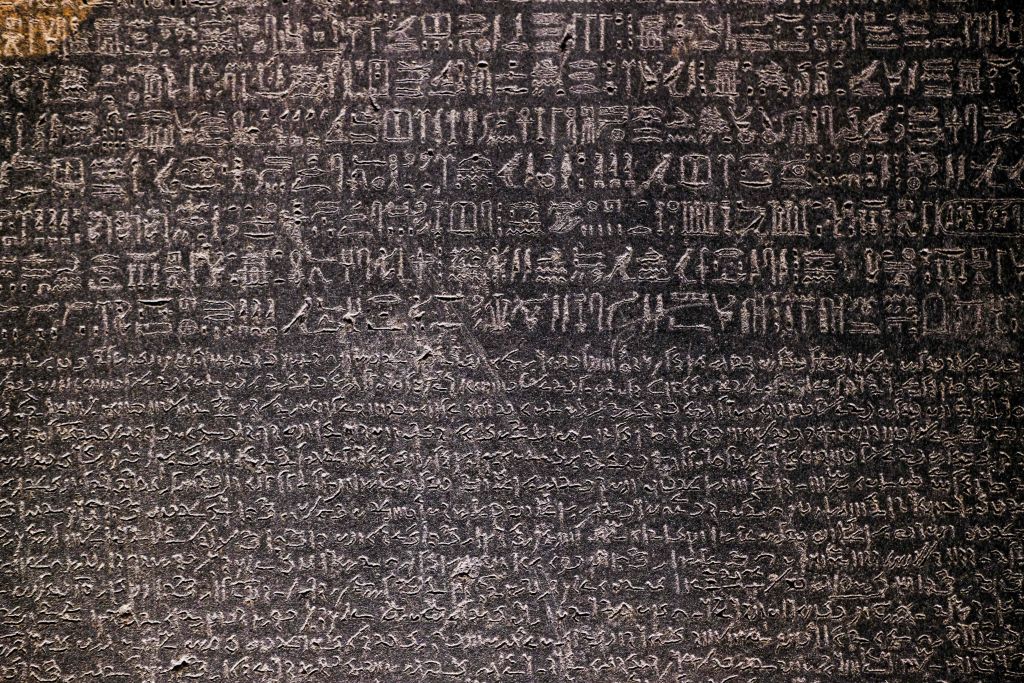

Despite these riches, more than 104,000 people have signed petitions calling for the return of the famous Rosetta stone. Yet the history of this object is not simply an Egyptian history. The inscription in three scripts, hieroglyphic, the less formal hieratic script, and classical Greek, is humdrum. It dates from 196 BC and honours a child king, Ptolemy V, recording in formulaic language royal gifts to several temples. The damaged black stone had been carted from its unknown place of origin to the foundations of a fortress at Rosetta or Rashida in the Nile Delta during the reign of Qaitbay, one of the Mamluk sultans of late medieval Egypt. These Mamluks were former Circassian slaves who had been exported from the Black Sea, mainly by Genoese merchants. Male Circassians with big muscles entered the palace guard and sometimes gained supreme power, Qaitbay being an excellent example. Female Circassians were famous for their beauty and might end up as sultanas or as sex slaves.

The history of this object is not simply an Egyptian history

The Rosetta Stone was discovered by Napoleon’s engineers in 1799, during the emperor’s brief occupation of Egypt, and subsequently confiscated by the British after Napoleon was chased out of Egypt. The stone’s history really begins around this point, because it was quickly recognised as the probable key to the decipherment of ancient Egyptian writing.

British attempts to get there first were outpaced by Jean-François Champollion’s definitive decipherment of key letters and words in France. This demystification put an end to centuries of endeavour by scholars and quacks who attempted to show that Egyptian hieroglyphs unlocked secret magical knowledge known to the pyramid builders which might, at a mundane level, solve the alchemist’s problem of how to manufacture gold from base metals. Seen from that perspective, the Rosetta Stone is an important part of the history of European scholarship, coming at the tail end of the Age of the Enlightenment.

The Egypt of the Rosetta Stone was a very different land to that ruled by its native dynasties. Its inscriptions were carved when the country was ruled by the Ptolemies, a Greek dynasty that culminated in the disastrous reign of Queen Cleopatra. The Ptolemies cleverly combined elements of ancient Egyptian culture with the Hellenistic culture that dominated the eastern Mediterranean, even fusing the Egyptian and Greek gods, to create the great god Serapis who was designed to appeal to the mixed population over which they ruled. The Library of Alexandria contained the largest collection of Greek literature anywhere in the ancient Mediterranean. Greek became the everyday language of large stretches of the Mediterranean.

This is not the ancient Egypt that will attract visitors to the new museum outside Cairo.

The history of the Rosetta Stone is not local but global, bringing in Greek kings of Egypt, slave sultans, French conquerors and the extraordinary intellectual feat of the French and English scholars who broke the hieroglyphic code. Its return would not reunite it with missing parts, as has been argued in the case of the Parthenon sculptures. Nor was it ever a treasure belonging to a wealthy court, like the Benin Bronzes. For most of its existence it had no owners at all. The British Museum needs to hold on to this discarded piece of ancient rubbish.

Comments