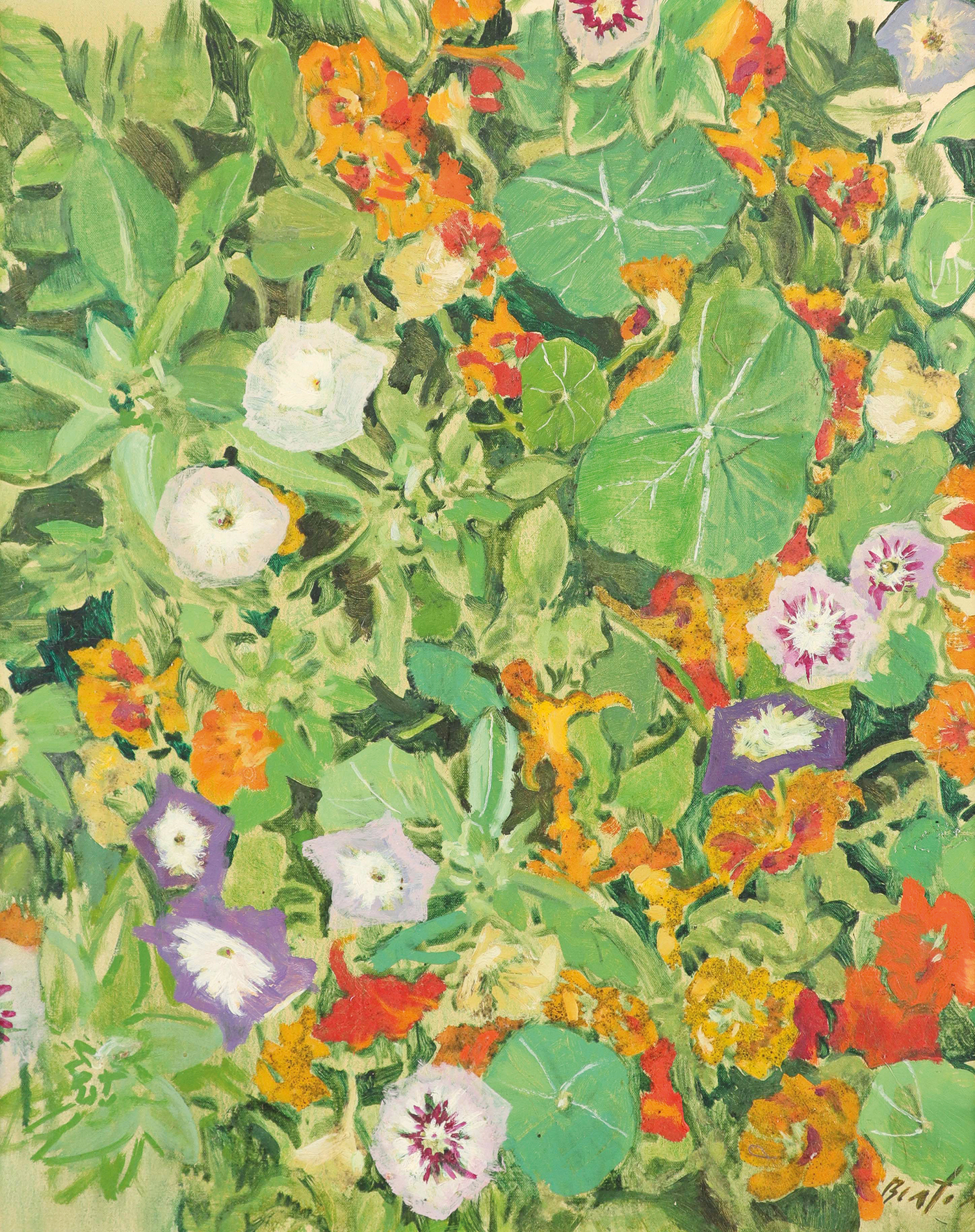

‘Remember, Roy, white flowers are the only chic ones.’ So Cecil Beaton remarked to Roy Strong, possibly as a mild put-down to the young curator. But it was a curious put-down to make because Beaton broke his own rule happily, buying mountainous armfuls of speckled yellow, pink and scarlet carnations at Covent Garden and longing to fill his borders with Korean chrysanthemums and purple salvias. This small exhibition at the Garden Museum enjoys the sweet-pea surface of Beaton’s creations, while giving a flash of the glinting secateur that also made up such an important part of his personality.

Beaton’s ability as an image-maker was astounding. Those famous photos of his Cambridge days with the Bright Young Things are still outrageous, a mad foray into camp pastoral. In a huge bromide print from 1927 of Rex Whistler strumming a lute in a melancholy grove, every leaf seems to sigh. We’re not altogether surprised to learn that Beaton left St John’s, Cambridge, without a degree, but a glittering career clearly beckoned. Stage design, photography, floristry, costume: he did them all.

He was a ruthlessly flattering photographer, making Wallis Simpson look positively vulnerable (a lonely wee thing against a big, wild wood), and he became sought after to the extent that he was also invited to photograph the Queen in 1939. He reached always towards elegance and fantasy, using blooms to garnish and garland. He was a master of allusion, adding an ear of corn to a country posy or using angel’s trumpets (Brugmansia) to create an ethereal atmosphere around the model Penelope Tree.

Of course Beaton loved flowers; he delivered beauty with a capital B. He was a committed aesthete, even during the war when, sent on a worldwide photography tour by the Ministry of Information, he gave advice to the staff of Government House, Calcutta, on their floral arrangements: ‘Use clear green lettuce leaves to enliven the tedium of endless cannas.’

But oh, the fear in Enid Bagnold’s letter, displayed here, in which she praises his designs for her new play The Chalk Garden so fulsomely, you just know there was a problem with them. ‘Please don’t let shadows come between you and me. You know I am unalterably fond of you.’ The paperback that accompanies the exhibition dishes. The rift between Bagnold and Beaton widened and lasted ‘many years’ when he was not invited to design the London transfer, although, on the plus side, this did leave him free to pursue a Pygmalion project… The Oscar statuette he won for ‘Colour Costume’ for My Fair Lady is on display here with a sweet note from Audrey Hepburn.

Stage design, photography, floristry, costume: Beaton did them all

It’s also fun to inspect his set-design model for Turandot, commissioned by the Met in 1961 and recreated by the Royal Opera House in 1963. Based on Boucher’s chinoiserie, which Beaton studied at the British Museum, it is stiff, with painted banana leaves and received Chinese adornment. It looks like a Regency-era vision of Puccini, lovely in its way, though unlikely to be revived.

The guidebook also tells how in 1938 he was sacked from his position at Vogue in New York for ‘inserting anti-Semitic text into a drawing’. ‘Beaton… blamed exhaustion but his favour in America was tarnished beyond repair.’ It was a temporary cancellation, however; adding flowers helps conceal a stink.

Curated by Emma House, the exhibition has been designed by Luke Edward Hall, who has added gorgeous free-hand murals, plus a dainty trellis arch etc. His lo-fi touches, such as a backcloth made out of literal tinfoil, plus cut-up suitcases, add a homemade feeling, and we remember that Beaton did it all with scissors, glue and charm. No air-freighted blooms? Plant yourself a cutting garden, as he did at Reddish. No waist? Cut one in with a retoucher’s blade.

Welcome to Cecil Beaton’s Garden Party. It lasts until 21 September, which is a lot longer than the real blooms at the Chelsea Flower Show over the river.

Comments