In 2022, Thailand became the first nation in Asia to lift its ban on cannabis (or ‘kancha’ in Thai) after decades of prohibition. A massive industry mushroomed practically overnight: you couldn’t turn a street corner in Bangkok without seeing a shopfront with ‘DOCTOR WEED’ in big, green, neon letters. But now, Bangkok’s hazy days might be over.

Last week, health minister Somsak Thepsutin signed a decree outlawing any sales without a doctor’s prescription. Since the vast majority of their customers are not epileptic or recovering chemotherapy patients, this means that most pot shops may well go out of business. Somsak even claimed he later plans to re-criminalise ganja outright, harkening back to the 2010s when the Kingdom of Smiles had the highest incarceration rate in Asia, with the vast majority of convicts imprisoned for drug offences.

It’s unreasonable to expect the Thai cannabis industry to simply disappear

Meanwhile, the southeast Asian country is engulfed in a political crisis. In May, an exchange of gunfire at the contested border with Cambodia left one Cambodian soldier dead. As tensions flared, a leaked telephone call between Cambodian strongman Hun Sen and Thai prime minister Paetongtarn Shinawatra revealed an overly-familiar dynamic between the two, with Shinawatra referring to Hun as ‘uncle’. The public, convinced they were being played, staged mass protests.

But, you might ask, how are these events connected? Weed has been a part of Thai culture for centuries, mainly in food – ‘tender ganja leaves’ features as a condiment in an eel curry recipe in Mae Khrua Hua Pa, the country’s oldest cookbook, first printed in 1908. Cannabis was banned under international pressure in 1934 and again in 1979. Meanwhile, the Bhumjaithai party, the main proponent of legalising marijuana, has quit Shinawatra’s ruling coalition over the Cambodia crisis, leaving the embattled prime minister weaker than ever – and putting her new weed ban at risk of flopping.

When the ban on cannabis was lifted in Thailand in 2022, it wasn’t actually formally legalised: it was merely decriminalised and removed from the list of illicit substances. This was the work of the then-health minister Anutin Charnvirakul of the pro-business Bhumjaithai party, who campaigned on a 420-friendly platform to win over farmers in the impoverished northeast. These farmers had traditionally harvested the plant but were now struggling, selling rice and sugar instead. Anutin’s order overruled the Narcotics Act, and although no actual regulations were put in place, it meant trading, growing or consuming Thailand’s favourite eel curry condiment was no longer a crime. This was widely taken to amount to the de facto legalisation of the substance.

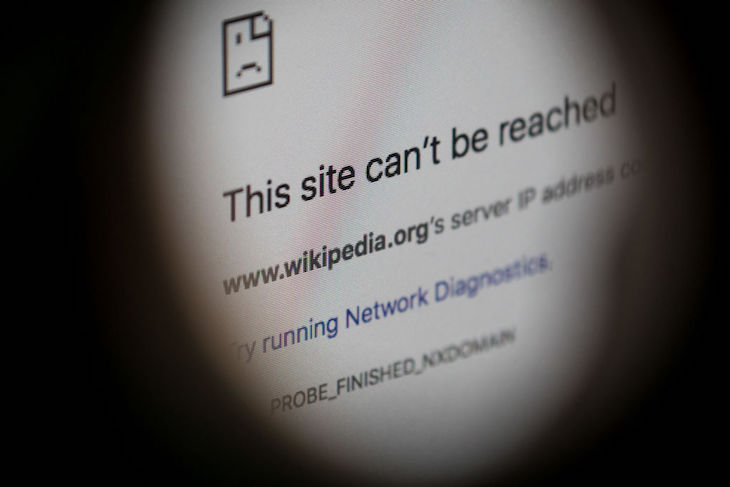

However, it appears this was too much, too soon. The stated reason for Thailand’s latest cannabis U-turn is public health, with Somsak claiming that marijuana-related hospitalisations had jumped sixfold since the reforms kicked in three years ago. While there has been no comparable data following the legalisation of marijuana anywhere else, such as in the United States, Somsak’s pronouncement ignited public fears about the cowboy cannabis market, where seemingly anyone could sell anything to anyone else, including children, with little to no oversight.

‘It was decriminalised, with the majority not understanding the rules and regulations,’ a licensed clinical cultivator explained off the record:

And since then, recreational use has gone rampant. The main issue is that nothing is enforced. They did a few checks on licences hanging on walls, and that’s about it. So for the last two years, they kept talking about making the regulations clearer. [But] there is a political issue going on, and the last week was a power move from one party against another against cannabis – nothing to do with making it clearer or doing the right thing.

Another reason for Thailand’s weed U-turn was outside pressure. According to the National Crime Agency, last year 800 couriers were busted carrying 26 tonnes of Thai ganja into Britain on behalf of international drug rings, hiding the contraband in their luggage. Perhaps Thai officials got sick of being yelled at by foreign dignitaries in meetings behind closed doors.

Of course, Thais are not the only guilty party here: in 2023, 26 young Americans with suitcases stuffed with marijuana were busted at British airports in the space of just eight weeks. Still, it’s amusing just how blatant these extra-legal activities in Thailand were. One weed shop I passed in central Bangkok even had a window sign reading ‘welcome British dealer’, and boasted of having their own farm. The shop was next door to a police station.

So what happens now? That depends on politics. Paetongtarn Shinawatra is the daughter of Thaksin Shinawatra, a media mogul turned scandal-mired prime minister. During his tenure between 2001 and 2006, Thaksin ordered the police to execute an extrajudicial ‘war on drugs’ in which roughly 2,500 suspects were liquidated – the majority of whom, it later transpired, were wholly innocent. Despite being ousted from power by a military coup, Thaksin is believed to continue pulling the strings of Thai politics from behind the scenes. But on Tuesday, amid mounting protests, lawmakers suspended his daughter Paetongtarn from her ministerial duties as a result of her leaked call with the Cambodian president.

Meanwhile, with its worth estimated to be over $1.2 billion (£875 million), it’s unreasonable to expect the Thai cannabis industry to simply disappear. The health ministry has therefore agreed to postpone the implementation of the new ban by up to 60 days, giving ganjapreneurs time to adjust.

But Shinawatra’s government might not even survive that long. Somsak Thepsutin is another ally of Thaksin, and a member of his daughter’s party. Should he lose his post amid the deepening political crisis, the responsibility of reining in Thailand’s wild west of weed will fall to someone else – if the ban goes through at all. Anutin Charnvirakul’s Bhumjaithai party, the architects of the marijuana revolution, are already eyeing up new coalition partners.

Comments