When William Morris was born in Walthamstow, in 1834, it was little more than a clump of marshland at the edge of the Epping Forest. This was the terrain of his free, frolicsome childhood, and it would forever form his image of humble, Edenic England, uncorrupted by the industrialist’s yoke. About the only thing that remains of this prelapsarian Walthamstow, amid its railway lines and brownfield sites, is the family home where Morris grew up, in some splendour – now a gallery dedicated to his artistic legacy.

‘To us pattern designers, Persia has become a holy land, for there our art was perfected’

The landscape has been supplanted, and much of the population transplanted. Next door to the William Morris Gallery is a Hindu temple where a gargoyle of the elephant deity Lord Ganesh keeps watch. Parading past the gallery every year is Europe’s largest birthday procession for the Prophet Muhammad. The manufacturing revolution Morris despised made Walthamstow a redoubt of the east London proletariat, which eventually encompassed a large community descended from Pakistani, Turkish and West Indian labourers.

What would Morris have made of this? His feeling for the British working class is well-known. ‘Art is man’s expression of his joy in labour,’ Morris wrote, believing that capitalism, by taking the artisan out of his own atelier and into the factory, had stolen from the creative natives of this land the artistic enjoyment that was their birthright. But how Morris would perceive immigration and the non-western cultures it has brought with it is much less studied than his socialism. William Morris & Art from the Islamic World, a new exhibition at the William Morris Gallery, may therefore be a turning point for our conception of an artist central to our national identity.

Morris is too often remembered as the wallpaper man – the designer of the patterns that once furnished middle-class drawing rooms, with their delightful names (‘Golden Lily’, ‘Strawberry Thief’) recalling some mythic English idyll. It is for these that Morris remains a household name. They reflect, according to the V&A – where Morris was in its early days an influential figure – ‘a very British take on pattern’. But how British really was it?

To anyone acquainted with what the architect Owen Jones called the ‘grammar of ornament’ – the title of his celebrated book that helped disseminate the patterns of the Islamic world – Morris’s designs appear, with their floral and geometric motifs, undeniably Islamic. The exhibition acknowledges the likes of Jones and the artist Frederic Leighton – of Leighton House fame, with its Arab Hall – as exemplary of the Victorian orientalism that also stimulated Morris. In the Morris and Co. patterns exhibited there are visibly Turkish motifs, such as the tulip head, and Persian ones, such as the flower garden.

But the exhibition makes a bolder assertion. Around 1870, Morris began acquiring antiquities from the Islamic world – though he had never stepped foot in it – and by 1885, we learn he had amassed so many items that he was a donor to Britain’s first exhibition of Persian and Arab art. Having scoured these collections, the curators display for us artefacts in which we may judge for ourselves the inspiration behind Morris’s patterns. We can thus observe how his ‘Flowerpot’ fabric sprung from the flower vase motif on an Ottoman Iznik-style tile Morris acquired from Damascus. Likewise, Morris’s ‘Wild Tulip’ wallpaper can be traced to the adornment on a Turkish porcelain bowl he owned.

This is not guesswork; it builds solidly on Morris’s statements. Regarding the objects that inspired his ‘Flower Garden’ textile that appeared in damask silk (a weave that itself testifies to the long entanglement of European fabrics with the Islamic world), Morris marvelled at the oriental mastery of colour: ‘all vermilion and gold and ultramarine, very beautiful and is just like going into the Arabian Nights’. (Morris elsewhere claims to know Edward Lane’s translation of the Thousand and One Nights by heart.) Morris professed his inspiration more generally in a lecture: ‘To us pattern designers, Persia has become a holy land, for there in the process of time our art was perfected.’

The collections exhibited here reveal Morris’s fascination with all the traditional Islamic arts and crafts one will find practised, to this day, in the qasbah of any near eastern city, from ceramics to metalwork, engraving, manuscript illumination, silk embroidery, and much else. As to the allure these had for him, the exhibition does not offer a full and satisfactory account.

It had, I think, something to do with that classic maxim of Morris’s: ‘Have nothing in your houses that you do not know to be useful or believe to be beautiful.’ The Muslim craftsman, crucially, fulfilled both – preserving an outlook long-dead in Europe since the Middle Ages. Muslims did not understand art for art’s sake, nor utilitarianism, the two vying modern philosophies of Morris’s own time, so inimical to him. Thus, the majestic brass peacocks displayed here would have had no value in Qajar Iran if they did not also burn incense (see below).

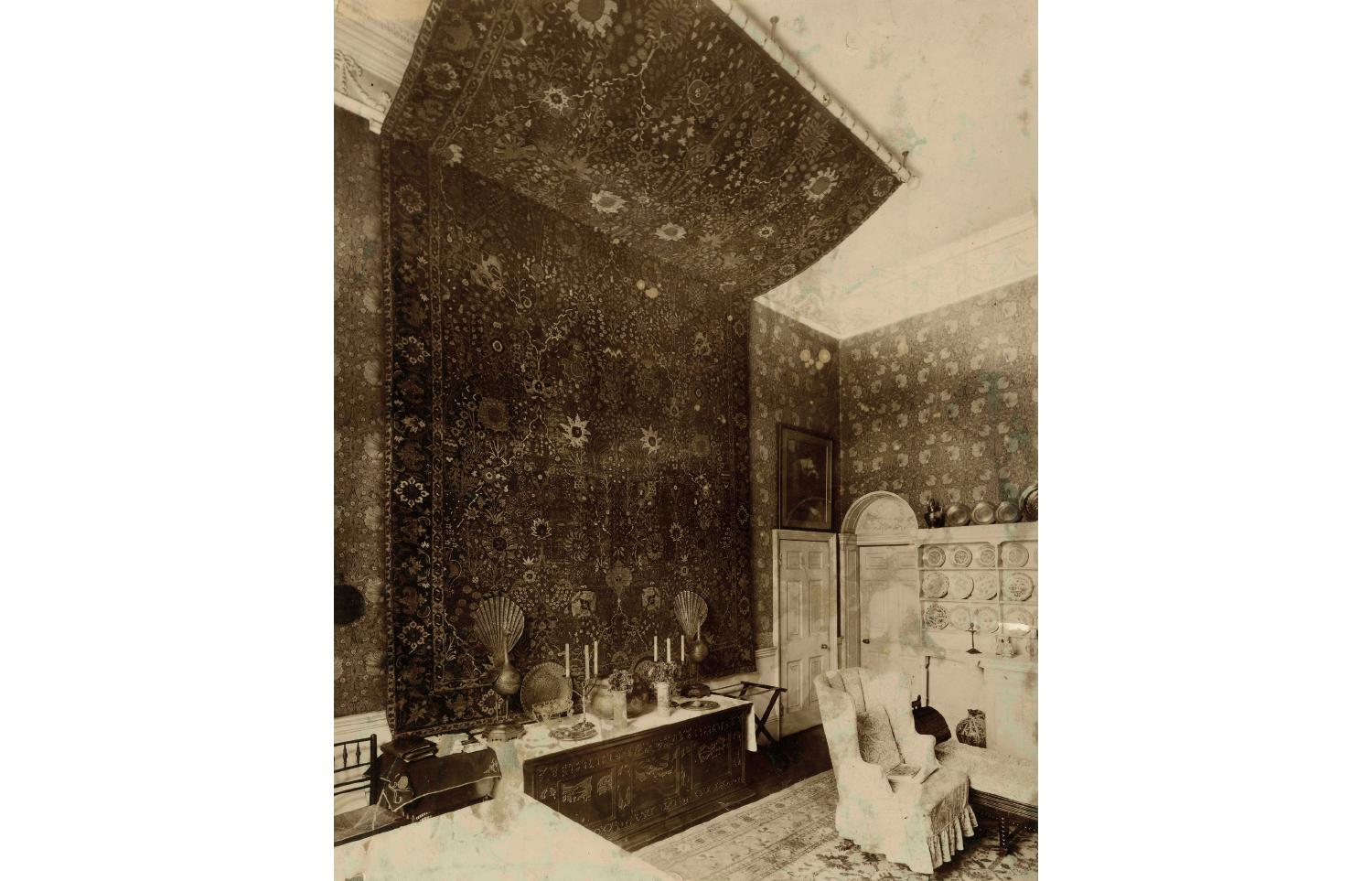

It was the most prototypically Islamic craft of them all, carpet weaving, that left the deepest impression on Morris. His Kelmscott residences proudly displayed his hoard of carpets procured from Turkey and Iran. Famously, as a referee for what would become the V&A, Morris also secured the acquisition of what remains one of the finest specimens of this ancient art, the Ardabil Carpet. Woven in 1539-40, it is the world’s oldest datable rug. While it is sadly not displayed in this exhibition, one may see it at the V&A in all its glory.

What the curators do offer are Morris’s own productions, his Hammersmith carpets, hand-knotted by women in London after the fashion of Muslim seamstresses. Morris hoped these would ‘equal the eastern ones as nearly as may be’. But they are plainly inferior, despite years of study and experimentation. They lack the lustre, the inspiration, so manifest in the oriental carpets on which Morris was modelling his textiles.

The rug was for Muslims what the church was for Christians: a place of worship

Once again, Morris’s own aesthetic theories help illuminate why. ‘The art of any epoch,’ Morris argued, ‘must of necessity be the expression of its social life.’ Art could not simply be appropriated without truly sharing the vision of the artist. For this reason Morris was conflicted about the gothic revival of his day. Medieval cathedrals were, for Morris, the apogee of architectural achievement. They had a unity of form and function; every arch pointed to the divine. But to build banks and train stations in this style in the 19th century was hopelessly inauthentic – they were bodies without souls.

So, too, Morris’s carpets. Weaving summoned the full extent of Muslim creative genius because, in theory, the rug was for Muslims what the church was for Christians: a place of worship. Morris never understood this potency. ‘Eastern rugs were not made to be trod on with hob-nailed boots,’ he would tell visitors to his home. This Islamic principle he had correctly picked up. But not the premise: that the carpet is a purified sanctuary where one may at any moment face Mecca and prostrate oneself to God.

Imagining the Muslim weavers of old, Morris revealingly attributes to them his own secular materialist worldview, even a European-style realism alien to traditional Muslim artisans. ‘In their own way, they meant to tell us how the flowers grew in the gardens of Damascus, or how the hunt was up on the plains of Kirman,’ mused Morris, ‘and what joy they had in life.’ In fact, Muslims’ portrayal of nature was strictly symbolic, expressing the divine bounty of joy in the paradise to come, not in the risible earthly life. He committed his own cardinal sin, in divorcing the weaver’s art from its social life rooted in Islamic sacrality. Thus, the absurdity – for a Muslim – of Morris’s carpets put to use as tablecloths. And yet, on one occasion at least, he did acknowledge that the destiny of all Islamic textiles was to be embroidered with ritual. For after his death in 1896, he had as his funeral pall a Turkish catma, a velvet brocade, just as the Ottomans buried their saints.

While Morris’s work as a designer and collector are suitably reflected in this exhibition, Morris’s influential critical views are somewhat overlooked. In these, Morris often touched on the West’s historic debt to the orient. Even his beloved gothic, which for Morris embodied medieval Christendom, was ‘traceable in the architecture of the Mussulman East’. And it’s in that same spirit that the curators of this treasure house have traced the links between Morris’s own work and the Islamic world, unearthing – as Morris did for his predecessors – the secret, underground river that flows, east to west, beneath our most cherished cultural monuments.

William Morris & Art from the Islamic World is at the William Morris Gallery until 9 March 2025.

Comments