Michael Tanner, who died yesterday at the age of 88, lived two parallel lives. To many Spectator readers, he was the magazine’s peerless opera critic: wise, passionate, thrillingly disputatious, intensely funny, extremely generous with the Semtex. Essential reading. He wrote The Spectator’s weekly opera column from 1996 to 2014 and continued to review – and raze to the ground where necessary – concerts, books, albums and opera, whatever we flung at him, right up until 2022.

To countless others, however, he was one of the great philosophical scholars. A celebrated authority on Nietzsche, he was the author of the introductions to the Penguin editions of The Birth of Tragedy (1993) – which he also edited – and Beyond Good and Evil (2003), a 1994 critical study of Nietzsche as part of the OUP’s Past Masters series, as well as a 1998 introduction to Schopenhauer. Watching him carefully elucidate and demystify Wittgenstein in this riveting BBC documentary from 1989 makes you realise why few who studied with Michael ever forgot him.

As a philosophy lecturer at Cambridge for 36 years and a life fellow of Corpus Christi – where he’d been since, I believe, his 20s, for a time also teaching English literature and taking on pastoral care – he educated a vast number of people. Many of these became lifelong friends. This being Cambridge, many others ended up running the country, and if you were lucky, he would sometimes point them out to you and tell you how fantastically thick they had been.

Opera and philosophy were by no means his only, or even primary, passions. His taste was thrillingly chaotic. A list of things he adored would have had to have included: Rilke, Peanuts (the cartoon), Astrid Varnay, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Gluck, Susan Sontag, Bruckner, Jeremy Corbyn, John McDonnell, Messiaen’s Saint Francis of Assisi, Celibidache, Thomas Mann. Things he loathed (he seemed to adore saying the word ‘loathed’, elongating the syllable as much as was humanly possible): Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Boris Johnson, Meyerbeer, Elfriede Jelinek, much of Richard Strauss, modern Bayreuth, Peter Conrad, Radio 3 presenters. He was somewhat pleased to retire from having to write exclusively on opera, as it allowed him the chance to put to paper his thoughts on the numerous other things he cared, or didn’t care, about – though I never got an analysis of Peanuts out of him however hard I tried.

There are others who knew Michael Tanner much better than I did. But as his editor during the last decade of his life we became very good friends. The ritual was often the same: we’d head to an opera or concert, then dinner, and while we chowed down a meal, he’d regale me with stories about the demonic aura of Karl Popper, or about hanging out with his beloved Mrs Furtwängler (Michael had produced an English edition of Wilhelm’s notebooks), or about his time spying on the Soviets while stationed in Lübeck in the Fifties.

And then there was Wagner. His greatest love. No one was more closely associated with the composer. No one was more trusted to expound on his work. No one had the capacity to elucidate its intricacies and difficulties more intelligently. Ask any Wagnerian where to start with the composer and they will invariably direct you to one of the two books Michael wrote: Wagner (1997) or The Faber Pocket Guide to Wagner (2010).

I dipped back into the Faber one as I took the train up to see Michael in hospital a few times last week. Humanity and insight on every page. I told him what a revelation his chapter on Siegfried had been. He was anxious there were still problems with it: ‘too late to do anything about it now,’ he huffed wryly. His chapter on Wagner’s anti-Semitism ends with a fantastic line (one that gives those of us wishing for an end to today’s interminable culture wars a faint glimmer of hope): ‘And that is where things still stand – and will do until the disputants become so bored with making their points and listening to the other side making theirs that the discussion will peter out.’

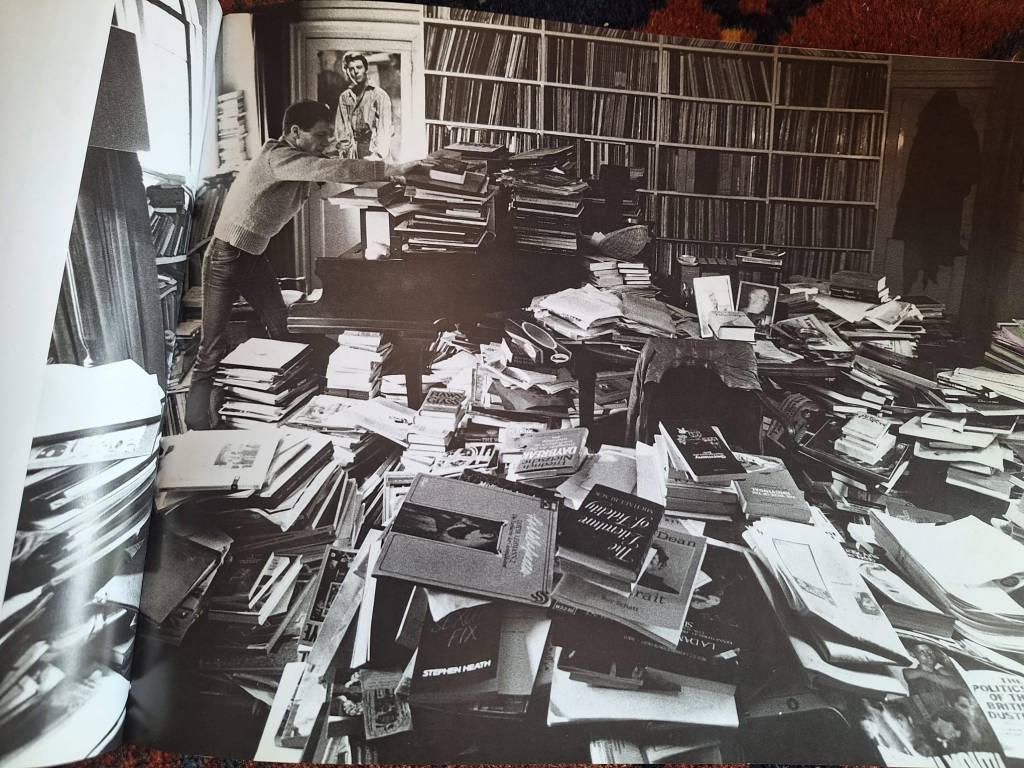

He seemed to never stop reading and listening and writing. He would sometimes hint at there being a set of memoirs in the works. A tantalising prospect if ever they were to see the light of day. In the meantime we have 26 years’ worth of reviews. On 13 July 1996 he introduced himself to readers for the first time:

I can hardly believe my luck in being asked to write regularly in this capacity for The Spectator. After a few weeks of jubilantly telling people about it, in a shy kind of way, unease began to enter the scene too, inevitably. Some of the unease is merely neurotic, some of a kind that it might be as well to air before I write my first actual review.

Brilliant, witty, soul-stirringly withering – but a very lovely and sweet man too.

A celebration of the life of Michael Tanner will be held on 26 April, 2 p.m., at Leckhampton, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge. All are welcome.

Comments