Englishness is big business in the nation of shopkeepers, and not just in politics and tourism. In literature, the gypsy scholars of Clan Macfarlane range freely across the hills and lexicons in search of old England, the dying and undead. This paperchase confirms that a change in the self-image of the English is afoot too. For centuries, the English poured into their cities. Now, they are trickling back out to the countryside. London excites precisely because it is another country, from a future that at least 54.8 per cent of the English prefer not to live in. But what does the returnee know of England who only London knows?

In 1997, Little, Brown published Clive Aslet’s Anyone for England? as ‘A Search for English Identity’. Twenty years on, the same publisher gives us Robert Winder’s The Last Wolf, with a subtitle promising a search both complete and elusive: ‘The Hidden Springs of Englishness.’ For Winder, the erstwhile literary editor of the erstwhile Independent, the springs of Englishness are environmental and medieval.

Geography is history, Montesquieu argued in L’esprit des lois (1748). The warm Gulf Stream and inclement rain shaped English agriculture and settlement. The rain fed the grass and the wheat. The wheat and the rain combined with the gist, as the Anglo-Saxons called yeast, to make cakes and ale. The grass fed the sheep, and the sheep, apart from feeding the shepherds, fattened the wool dealers. Add coal, and Winder can reduce Englishness to a‘playful equation’: E = cw4 (Englishness = coal x wool, wheat and wet weather).

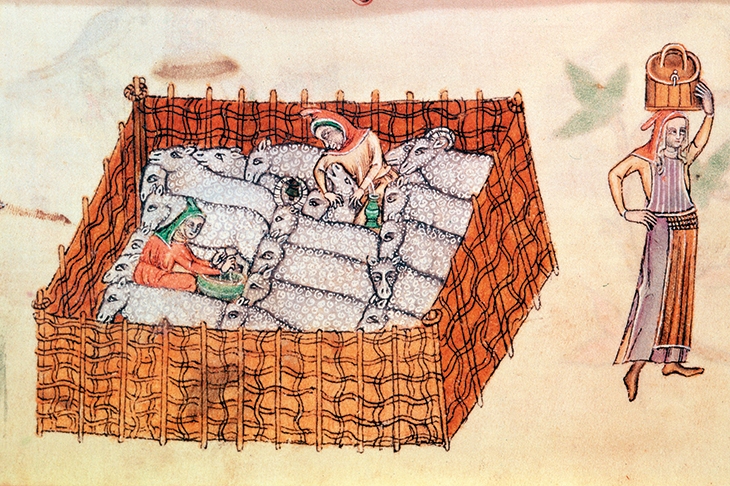

By his own argument, Winder should subtract a fifth ‘w’, the wolf. The ovine economy of the Middle Ages required ‘a tamed terrain, scoured of exciting wild animals’. In 1281, Edward I commissioned Peter ‘The Mighty Hunter’ Corbet to clear the last wolves from England’s forests. By 1290, Peter had earned his nickname and England could become an ‘enormous sheep estate’.

In the same year, Edward I expelled England’s ‘Jewish financiers’ along, we must presume, with their Jewish financier wives and children. Winder finds this murder and expropriation a bit ‘dismaying’, like rain at a village fete, and interprets it as a form of proto-Brexit. But the extirpation of the wolves and the Jews are linked, and neither have much to do with Brexit. The Anglo-Norman economy was built with loans from ‘Jewish financiers’. Debt and wolves were the two obstacles to its further growth. Shakespeare, a son of the wool trade, calls Shylock a wolf.

The Last Wolf is an engaging ramble through the wool towns and open ranges of medieval England. The sheep economy made ‘a love of the outdoors’, a ‘preoccupation with the weather’ and ‘a national love of dogs’ all seem ‘stereotypically English’ and ‘innate’. Medieval England had ‘more mills than churches’, and ‘the whirring creak of the watermill’ was as ‘integral to the English scene as birdsong or the bleating of lambs’. And did the English preference for soft white bread inspire the ‘serrated edge’ of the English bread knife?

These springs are as much neglected as hidden. Under the Tudors and Stuarts, another ‘w’ and another ‘e’— salt water and enclosures — profoundly changed the equation of English commercial life, and the face of the landscape too. The wool trade had always been a sea trade, and the Black Death, by clearing more land for sheep, accelerated the formation of giant ranges and made the surviving sheep magnates more powerful. But our ‘stereotypically English’ hedgerows and urban habitats are the legacies of land enclosures, and the luxurious classical pastoral of the Georgians — beef and claret, not lamb and beer — rested on Atlantic and Indian commerce.

Winder rightly emphasises that the precociously commercial life of medieval England fostered the change from the woollen world to the wooden world of maritime empire. But he does not address the two most important developments of all: the transition from Latin and Old English to the hybrid tongue of Langland, Chaucer and the Reformation. The Protestant revolt turned England’s sailors and businessmen towards the Atlantic, crystallised the English language, and created the trifecta of national identity: land, language and a national religion. As a ‘Jew made in England’— not, unfortunately, by financiers—I would argue that this trinity not only created the richness and density of Englishness, but also its exclusivity.

The Last Wolf is a good yarn, but not all of the springs of Englishness come from the old England of the shepherds. When Disraeli identified ‘two nations’ among the products of modern Englishness, he might have added another two nations — the England of before and that of after the Reformation.

Comments