‘Dearest Gwen,’ writes Celia Paul, born 1959, to Gwen John, died 1939, ‘I know this letter to you is an artifice. I know you are dead and that I’m alive… But I do feel mysteriously connected to you.’ And well she might, because the parallels between the lives of the two painters are legion. To take the most obvious: both were students at the Slade, both had relationships with much older artists and both came to be seen, for a time at least, through the prism of their association with men. Gwen John was the older sister of the once more famous Augustus and model and lover of the French sculptor Auguste Rodin; Celia Paul, the lover, model and mother of a son of the painter Lucian Freud.

Paul stepped into the limelight three years ago with her first book, Self-portrait, a devastatingly honest account of a painter’s life. The current volume is written around a series of 26 letters she has written to Gwen John, and is at once diary and confessional, biography and autobiography and something between the two. It maps the landmarks of the two artists’ lives, exploring their motivation through the tenuously imagined dialogue of two kindred minds.

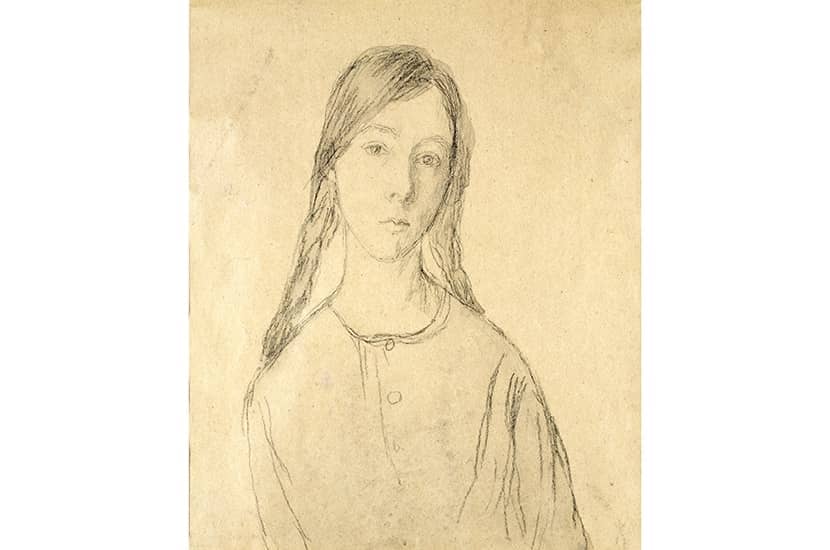

Although some of the emotional traumas here will be familiar to readers of Paul’s previous volume, it is Gwen John’s life as much as her own that is the focus of this book. The intense stillness, calm and beautifully modulated tones of John’s painting give little clue to a life of roiling emotion and fiercely driven passion. After a childhood in Wales and student years in London, she escaped to Paris and spent the rest of her life in France. In her later years in Meudon she lived in an abandoned hangar, often sleeping in the garden. ‘She wasn’t chaste or subdued,’ Augustus wrote of her, ‘but amorous and proud. She didn’t steal through life, but preserved a haughty independence which people mistook for humility.’ Celia Paul is probably rightly wary of Augustus’s pronouncements, but they cast a useful light on a life which might easily be seen as a series of violent attachments – Rodin being the most significant – and painful rejections.

In all of this Paul finds echoes in her own life, as she does in the sense of compulsion that lies behind both vocations. ‘I tell you,’ Gwen John wrote to her close friend Véra Oumançoff, ‘that sometimes my work tires me. It isn’t often a pleasure. It has always been tiring and difficult, I do it as I do my housework because it has to be done.’ In the same spirit, Paul would lie on her studio floor planning her next work until she had gathered the strength to begin. And when it comes to describing the genesis and construction of her own paintings she renders the art historian of the future redundant. ‘Words don’t come easily to me,’ she says, but in writing of the world around her, about portraits of herself, her mother and sisters, seascapes, the view from her flat opposite the British Museum, paintings of trees, streams and clouds, you would never know it.

Her painting of a copper beech was ‘torn out of me like a demon being exorcised’. To her the finished painting resembles ‘a controlled explosion’ and she is filled with ‘such uplifting joy I can’t even begin to describe the happiness’. A fortnight later she looks at it again and decides it’s not right, scolding herself for trusting the ecstasy she had felt. Back onto the easel it goes, ‘weighted down and suffocated by its own darkness’. The artist lets in air and light in the interstices of its branches and leaves and it is ‘alive and breathing’. And here it is, reproduced in the book, in all its surging energy, a tree electrified and sparking with light all the way up its trunk to the ends of its branches.

More tellingly still, she writes about a portrait of herself with Lucian Freud and his daughter Bella. This was started after Freud’s death and is based on a photograph of the three taken in 1983. The painting comes easily at first, but for days she tries and fails to capture his head. ‘I feel sick. I work into the night and early hours,’ but to no avail. She gives up and paints it all out. Then some three weeks later she begins again and – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing as Hopkins put it – ‘this time Lucian is alive. I’ve captured him alive.’

This book lets the reader into a world of sadness, loneliness and isolation. At its heart, however, is that unexpected kernel of confidence and self-belief that the author shared with Gwen John. Celia Paul felt that the world censured her for not being a better mother. ‘But my desire,’ she writes, ‘was for the shadowy crime of painting. I longed to be alone and free to create my secret unsettling art.’ Not a comfortable thought, but then this doesn’t set out to be a comfortable book.

Comments