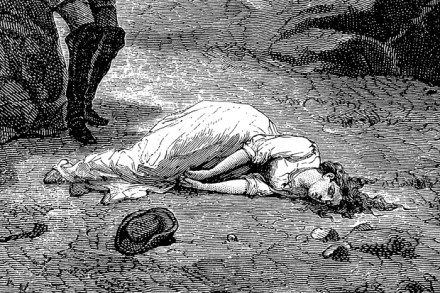

Death in Greenwich

With the current political saga running in our heads, trumping all other stories, it has been hard to concentrate on the bedside book over the last few weeks. When, in this true Victorian murder mystery, I came to the sentence, ‘Ebeneezer Pook, however, had no intention of succumbing to the crowd’s pressure’, all I could see in my head was Jeremy Corbyn emerging from his house, ducking under the prickly rosebush and refusing to stand down. And when I came to this complicated passage: Mrs Thomas’s story buttressed the account that William Sparshott had given and would dovetail with the account Olivia Cavell was about to give. Nevertheless, Coleridge could