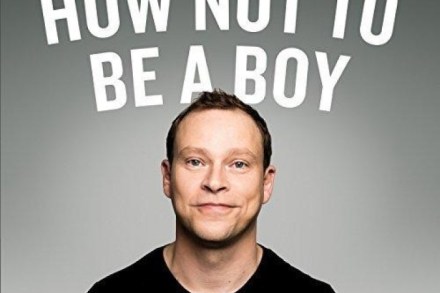

From The Archives: Robert Webb

26 min listen

The Book Club is taking a brief Christmas break, so we have gone back through the archives to spotlight some of our favourite episodes. This week we are revisiting Sam’s conversation from 2017 with Robert Webb. His moving and funny book How Not To Be A Boy turns the material of a memoir into a heartfelt polemic about what he calls ‘The Trick’: the gender expectations that he identifies as causing many of the agonies of his adolescence and young manhood. What is it to be a man? Are we doomed to lives of inarticulacy, shagging, fighting and drinking — giving pain and fear their only outlet in anger?