Unsettlingly faithful to the spirit of Schiele: Staging Schiele reviewed

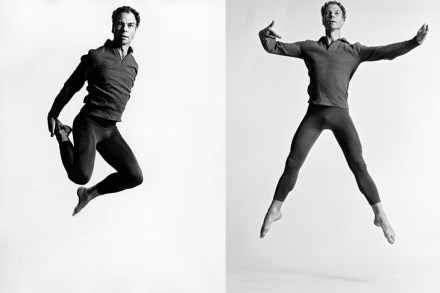

‘Come up and see my Schieles.’ Those were the words that ended a friend’s fledgling relationship with an art collector. One evening looking at Egon Schiele’s skinny naked scarecrows was enough. Staging Schiele, a one-act dance piece by choreographer Shobana Jeyasingh, is unsettlingly faithful to the spirit of Schiele’s art. If the skin creeps, if the stalls recoil, then the dancers — one man and three women — have done their job. The opening solo is danced by Dane Hurst stripped to his pants in a powerful display of athletic narcissism. His only partner is a small hand mirror at which he lunges and thrusts. Hurst sprawls and crawls and