More misogynistic than the original: ENO’s Orpheus in the Underworld reviewed

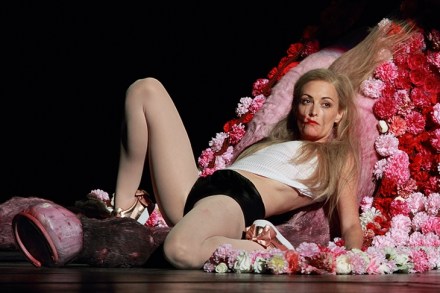

It’s Act Three of Emma Rice’s new production of Offenbach’s Orpheus in the Underworld, and Eurydice (Mary Bevan) is trapped in the backroom of a Soho peep show. But that doesn’t really matter because Jupiter (Willard White), a cigar-toking love walrus in a silk bathrobe, has transformed himself into a fly and is about to ravish her, once he’s worked out the practicalities of doing so while three millimetres long. Eurydice’s more than game. ‘Zzzz, zzz,’ she sings, draping herself lasciviously over the mattress. ‘Zzzz, zzz,’ buzzes Jupiter, wings popping erect. Rice’s puppeteer darts about with a toy fly on a string, dressed in a black catsuit and (the killer