Exceptional career woman, unexceptional painter: Lavinia Fontana, at the National Gallery of Ireland, reviewed

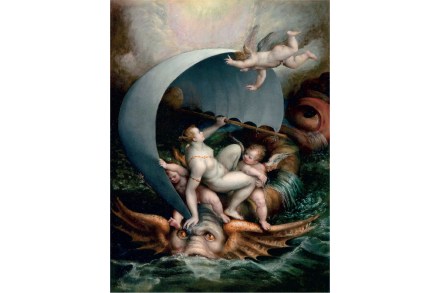

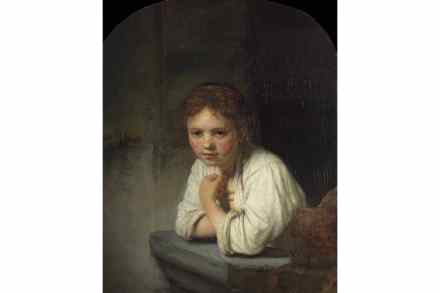

Reviewing the Prado’s joint exhibition of Sofonisba Anguissola and Lavinia Fontana in the Art Newspaper three years ago, Brian Allen pronounced it well worth seeing but predicted that each of these pioneering 16th-century women artists ‘would wither in the spotlight of her own retrospective’. Was he right? In its new monographic exhibition devoted to Fontana, the National Gallery of Ireland puts his waspish prediction to the test. Her ‘Galatea and Cherubs’ and ‘Venus and Mars’ are believed to be the first nudes painted by a woman Ireland’s National Gallery was an early investor in Fontana, acquiring her most ambitious work, ‘The Visit of the Queen of Sheba to King Solomon’