Unclear Handeling

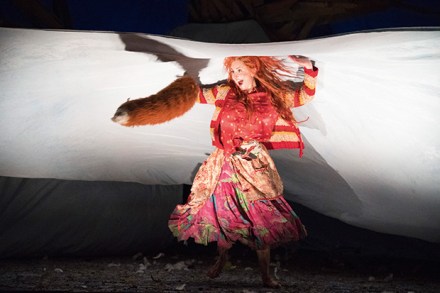

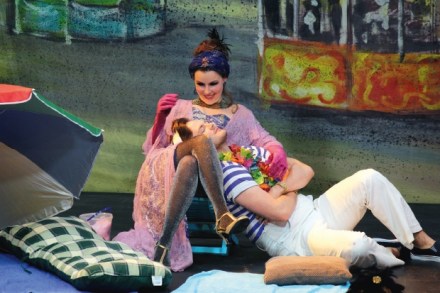

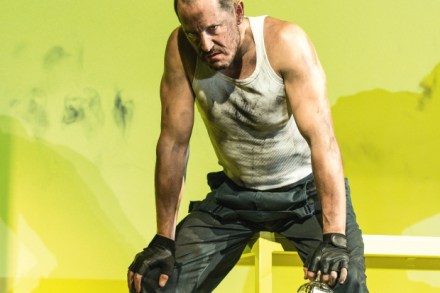

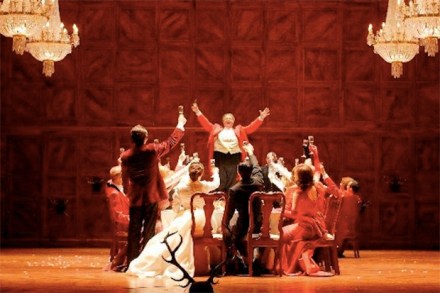

ENO has revived Richard Jones’s production of Handel’s Rodelinda. It was warmly greeted on its first outing in 2014, though Jones was, as he remains, inveterately controversial. The opera itself seems to command universal admiration among Handelians, and widespread approval among those of us who have never quite managed to call ourselves that. The most unequivocally positive response I’ve had to it was at Glyndebourne in 1998, where it was produced as if it were an early black-and-white film, and superbly conducted by William Christie. Viewing the DVD has confirmed my warm feelings about it. My chillier feelings about ENO’s in many ways excellent account are prompted, first, by Jones’s