Across the literary pages: Amis Asbo special

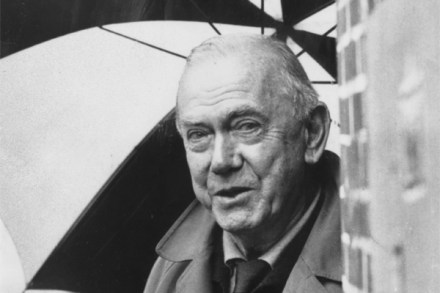

The promotional tour for Lionel Asbo: State of England has been suspiciously quiet. The fact that Martin Amis hasn’t sworn, bitched or nominated the queen as guinea pig for euthanasia booths stirred the press into feverish levels of anticipation. Had the OAP (Old Age Provocateur) finally lost his teeth? Or was he simply biding his time before biting back? A satire on Lionel Asbo – Wayne Rooney look-alike and dedicated chav – and his lottery win, it seems written to offend … even without subplots involving teenage pregnancy (she &”was six months gone when she sat her Eleven Plus”), incest with a thirty-something year old granny, pit bulls and acid attacks.