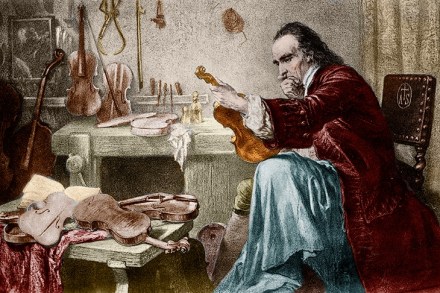

Haunted by the soft, sweet power of the violin

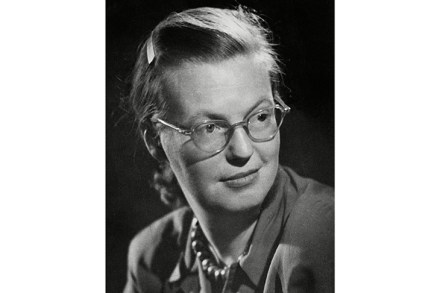

An extraordinary omission from Neil MacGregor’s A History of the World in 100 Objects is the lyre, the instrument closest to Homer’s heart. Without it, the evolution of bowed stringed instruments — rebec, lira da braccio, violetta — would not have taken place. Ipso facto, there would be no violin, nor its larger siblings; no chamber music, no orchestra, no Hot Club de France. In such a parallel world, Helena Attlee would be much time-richer, given that she has spent more than four years researching the provenance of a single violin. At a Klezmer performance in a small Welsh town the author is moved by the joyous but wistful celebratory