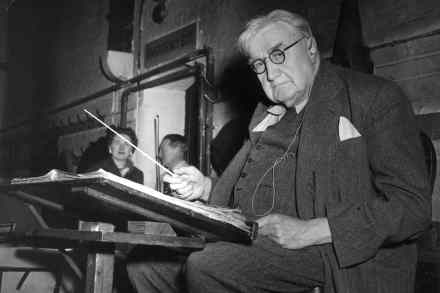

Ralph Vaughan Williams: modernist master

To look at a picture of Ralph Vaughan Williams is like contemplating an image of a mountain. Not the elegant, keen-eyed Edwardian intellectual whom we sometimes glimpse on CD sleeves or in concert programmes; I’m thinking of the portraits from the last decade of his long life. By the 1950s ‘RVW’ had been the father of British music for so long that he already seemed like part of the landscape, and he looked it too. The craggy jowls, the weathered thatch of grey hair; that questioning gaze — and beneath it all, those great, tumbling scree slopes of rumpled tweed. In his 150th anniversary year he’s still there, towering in