Merging poetry and song

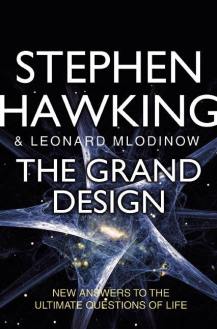

The best book so far about Bob Dylan, the only one worthy of his oeuvre, is his own astonishing Chronicles, Volume One (2004), but while we wait for the next fix, Bob Dylan in America will keep the withdrawal symptoms at bay. Sean Wilentz is a history professor at Princeton, and author of books about Jefferson, Lincoln and Reagan. He is also a second-generation hipster and a Dylan fan since 1964, when he first saw him play. Wilentz planned this book, he explains, as ‘a coherent commentary on Dylan’s development, as well as his achievements, and on his connections to enduring currents in American history and culture’. As a critic