Paul Johnson reviews Roy Hattersley’s life of David Lloyd George

No politician’s life is so difficult to write as Lloyd George’s. All who have tried have failed, and wise heavyweight historians have steered clear. I applaud Roy Hattersley’s courage in tackling this rebarbative subject and congratulate him on his success in making sense of Lloyd George’s early life up to his emergence as a major figure in parliament. Thereafter, however, he tends to lose his way in the trackless jungle of endless political crises during Lloyd George’s 16 years in office, festooned as they are with the undergrowth of his financial fecundity and the florid canopy of his love affairs. Hattersley emerges from this rainforest exhausted, to be faced with the remaining 23 years of Lloyd George’s life, for he was only 59 when he fell irrevocably from power in 1922, and thereafter nothing important happened.

One problem is Welsh. Hard to get inside the man without a knowledge of the language, and of Welsh culture, based on land-hunger. He barely believed in God, and the Irish leaders who negotiated with him claimed he lacked a soul, certainly a conscience. But he was a fine judge of sermons and loved to sing hymns. Tom Jones, a Welsh speaker, scored here, and his slim volume, written in 1951, is still probably the best biography, when supplemented by the three tomes of Cabinet diaries, based on verbatim notes. He and Lloyd George often conversed in Welsh to baffled colleagues and eavesdroppers. Lloyd George was a Celt. He had no fundamental beliefs or principles, but could be captured by ideas, especially if they verged on the poetic.

Keynes, who observed him closely during the Versailles negotiations of 1919, wrote:

He is rooted in nothing; he is void and without content; he lives and feeds on his immediate surroundings; he is an instrument and a player at the same time, which plays on the company and is played on them too; he is a prism . . . which collects light and distorts it and is most brilliant if the light comes from many quarters at once; a vampire and a medium in one.

Tom Jones used a different metaphor:

His mind resembled a signalman’s in a busy railway station, Clapham Junction, for example, with steam and electric trains travelling at varying speeds to the coast, to the country, to London. He pulled the levers, and the traffic moved in Westminster, in Whitehall, in Fleet Street, in party offices, in town and village halls, in polling booths. His friends were few, his instruments many, his acquaintances legion, his interventions innumerable, and his political curiosity inexhaustible. Basically he was a hard realist, with no illusions about men or movements.

In one sense his achievements are formidable. He laid the foundations of the Welfare State with old- age pensions and national insurance. He provoked the row with the Lords which ended in their emasculation. In the Great War he first solved the munitions shortage, then ousted Asquith and drummed the nation to victory. He solved the problem of Ireland by dividing it. He enlarged the British empire and presided over it at its greatest extent. He smashed up the old Liberal party of Gladstone and would have done the same with the Tories had not Baldwin bundled him out of office for ever.

But there was a Celtic mist over all these doings. I recall in 1948 reading an essay on the battle with the Lords when my tutor A.J.P. Taylor rudely interrupted: ‘What precisely was the content of Lloyd George’s 1909 budget?’ I was unable to give a satisfactory answer.

But what was it all about? Hattersley reminds us that taxation on land values, the incendiary element, was reckoned to bring in only half a million. The rest were increases, none outrageous, in existing taxes. Again, though few at the time or since have doubted that Lloyd George won the war, it is hard to see exactly how. His mistake was not to take advantage in 1922 to sit down at once to write his war memoirs, thus getting his version set down before others finished theirs. By contrast, when Churchill was ousted in 1945, he settled immediately to writing his account of the second world war, so that it became, and remains, the orthodoxy — thus proving his wife right in predicting that his electoral defeat would be a blessing in disguise. But some — Bob Boothby, for example, who worked with both — even maintained that Lloyd George was the greater war leader and man.

Hattersley, however, sees Lloyd George as essentially a destructive character. Certainly his rhetoric was excoriating and usually crackled with personal abuse. He would not have been able to cope with our new hate laws, for arousing hatred was his most marked political gift. Even his casual spoken asides were flecked with venom. Instructing his deputy, Bonar Law, to sack a middle-ranking minister he snapped: ‘I don’t mind if he is drowned in Malmsey wine, but he must be dead chicken by midnight.’ Yet this killer instinct was matched by an extraordinary ability to feed men lies, half truths and high-minded waffle, a capacity which brought short-term triumphs and long-term distrust.

Though habitually deceitful, Lloyd George could emit flashes of self-knowledge. Early in his relationship with his long-suffering wife Margaret, he wrote: ‘My supreme idea is to get on. To this idea I will sacrifice everything — except, I trust, honesty.’ The mendacious qualification was of course the cloven hoof.

It is interesting that the nickname ‘the goat’ was first bestowed on him by an obscure civil servant to describe his propensity to gobble and digest masses of official papers. It stuck because it fitted perfectly his unswerving pursuit of women as counterpoint to his chase after power. Churchill, to his lifelong benefit, always remained faithful to Clementine — one reason why his career was a story of ultimate success and happiness. For to a public man, persistent adultery is prodigal in time and energy, risk and worry, and likely to provoke universal distrust.

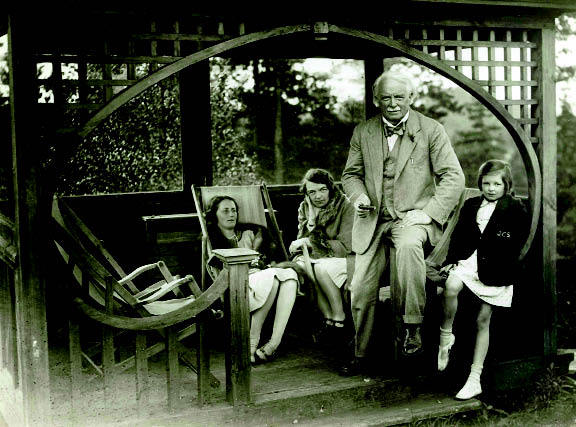

The trouble with Lloyd George, as Hattersley notes, is that apart from a little golf, women were his only relaxation. Whereas Churchill had his writing and his painting in which to invest any passion left over from politics, Lloyd George had only sex. Hattersley writes: ‘His sexual compulsion was so great that in the 21st century it would have been diagnosed as a psychotic condition.’ That is going a bit far; but there may have been something abnormal about it. Frances Stevenson, who was hired as a governess for his daughter Megan, became his mistress when she was 23 and he 46 and remained so until she became, just before his death, the second Countess Lloyd George. She described him at their first meeting:

The sensitive face with deep furrows between the eyes: the eyes themselves, in which were all knowledge of human nature, grave and gay simultaneously … a magnetism which made my heart leap and swept aside my judgment.

There may have been something else more directly physical. A.J. Sylvester, his factotum during his twilight years, described Lloyd George without his clothes on:

There he stood, as naked as when he was born, the biggest organ I have ever seen. It resembled a donkey’s more than anything else . . . No wonder they are always after him and he after them.

Sylvester added in his diary:

If LG gave his mind to thinking how best he could help his country instead of thinking cunt and women, he would be a better man.

As it was, ladies were always slipping in and out of the political scenario. Legal threats of paternity cases and divorce citations were normally dispelled by stout lying, but the notorious ditty ‘Lloyd George knew my Father’ was not without substance. Lloyd George himself made no general pronouncement on his sex life other than objecting to his bust in the House of Commons: ‘It make me look lecherous.’ He was also perhaps the greatest political talent in 20th-century Britain, which the country, aided by his own follies, cut off in its prime.

Comments