The naked and the dead

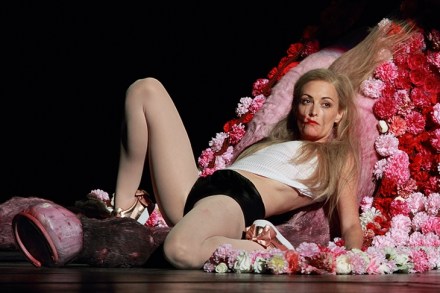

Yes, Oscar Wilde never wrote it. No, Strauss didn’t intend it. In fact, the composer famously demanded the Dance of the Seven Veils be ‘thoroughly decent, as if it were being done on a prayer mat’. But that doesn’t stop this striptease and musical money shot being the look-but-don’t-touchstone of any Salome. A blonde, blank-faced Barbie doll in gym knickers, vest and shiny trainers stands in a spotlight, a baseball bat in her hands. Strauss’s oboe begins its suggestive arabesques but Salome remains quite still, her eyes fixed impassive, unblinking on the audience. Eventually her hips begin to twitch, her back arches and she goes sullenly through the motions of