Great leaps forward

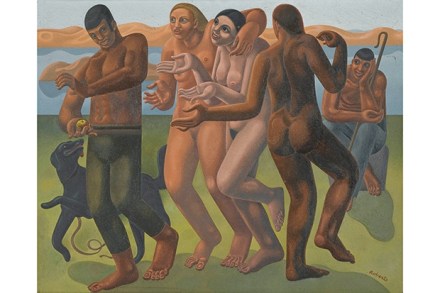

In the 1940s Lucian Freud took another young painter, Sandra Blow, up to the top of a bombed church in Soho. There were just two prongs of masonry left and Lucian promptly launched himself through space from one to the other. ‘You can’t possibly expect me to do that,’ she exclaimed. ‘Just think of it as if you were on the escalator in Selfridges,’ he replied. History does not relate whether she was persuaded by this comforting analogy, but as a small exhibition at the Fine Art Society demonstrates, Blow (1925–2006) spent the rest of her career making jumps. These were mainly of the visual and stylistic variety. There is