Vincent van Gogh spent a remarkably short span of time in the southern French town of Arles. The interval between him stepping off the train from Paris on 20 February 1888 and his departure for the asylum at Saint-Rémy on 8 May the following year was a scant 14-and-a-half months. For some of this time the painter was hospitalised and seriously ill, yet in this brief period he produced not just one, but several of the greatest pictures in the history of art.

It might be thought that there was nothing more to discover about Vincent in Arles, a subject that has been so discussed, investigated, dramatised and filmed over the years. But this year a flurry of fresh information has appeared. In the summer, strong evidence emerged in Van Gogh’s Ear, a book by Bernadette Murphy, about how much of that organ he had sliced off on the evening of 23 December 1888. It was not just a portion of lobe, as is often believed, but the whole damn thing.

Now, in Studio of the South: Van Gogh in Provence (Frances Lincoln, £25), Martin Bailey, an indefatigable and much-respected researcher into Van Gogh’s life and art, has lucidly marshalled the facts of the case, and added several fresh pieces of information.

One poignant detail he underlines is that, on the very day that Vincent descended into delirium and mutilated himself, his youngest sister Wil passed on a compliment from Jozef Israëls, a famous older Dutch artist. On seeing ‘Pink Peach Trees’, one of the paintings of orchards in blossom from the previous spring, Israëls exclaimed that Van Gogh was a ‘clever lad’.

This undercuts another persistent legend: that his work was neglected and derided during his lifetime. In fact, very few got a chance to see the great paintings from Arles and Saint-Rémy until near the end of Van Gogh’s life. As Israëls’s remark shows, those who did often liked them.

Had this praise reached Vincent, would it have forestalled his breakdown? There were other factors pushing him over the edge, one of which, as Bailey argues, was the announcement that his brother Theo had become engaged. Through assiduous detective work he has demonstrated that a letter, almost certainly containing the good news, arrived on the morning of the 23rd. This might well have caused Vincent’s anxiety levels to surge, since he depended on Theo for money, and the latter would now have a family to support.

This could well have triggered the catastrophe — although there was more than one factor undermining Van Gogh’s mental equilibrium. He had been working furiously hard for months, was probably drinking heavily, and his house-share with Paul Gauguin, the most fraught in art history, was about to disintegrate. There was also an underlying malady, probably inexorable and genetic, since his sister Wil later also became deranged.

Bailey’s book reproduces a large number of works, including a recently unearthed sketch of Van Gogh by his friend Émile Bernard, and the oil ‘Sunset at Montmajour’, which was rediscovered a few years ago. There is, however, a yet more sensational supposed find, which has just been announced: a unknown sketchbook that has — apparently — been preserved, unnoticed, in Arles since 1890.

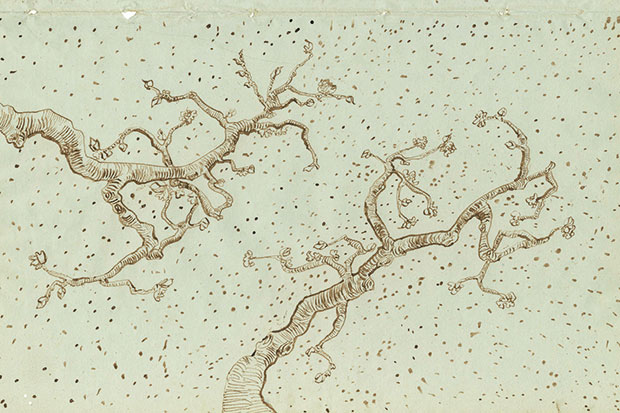

This, and the 65 drawings it contains, was revealed to the world this week at a press conference in Paris and in a book, Vincent van Gogh: The Lost Arles Sketchbook, written by a distinguished Canadian scholar, Bogomila Welsh-Ovcharov, with a foreword by Ronald Pickvance, doyen of Van Gogh specialists. It contains many versions of familiar subjects — the cornfields, the cypress and olive trees — plus a few novelties, including an alleged portrait of Gauguin and a strange self-portrait, quite unlike any other image of Vincent.

It is claimed that the sketchbook was presented to his friends and ex-landlords Joseph and Marie Ginoux, the proprietors of the Café de la Gare, by Van Gogh shortly before he took the train north to Auvers, where he killed himself a few months later. He did not give it to them in person,

but entrusted it to Félix Rey, the doctor who treated him immediately after the ear-cutting episode.

Dr Rey allegedly visited him at Saint-Rémy and carried the sketchbook back to Arles. Neither the gift nor this visit was previously known, but are referred to in another discovery — a fragmentary notebook recording various dealings at the Café de la Gare that was preserved with the drawings (which are not in a conventional artist’s sketchbook but a recycled commercial ledger).

There are several aspects of this provenance that make one feel cautious. It is surprising, for example, though possible, that such a valuable object should have lain around undetected for more than a century. However, that would not be so important if the sketches themselves were comparable in quality to the masterly paintings and drawings that Vincent was producing at the very same time. But they are not.

I must emphasise that I have not seen the originals, but judging from reproductions many of them are weak and some — especially the portraits — look positively inept, no better than amateur art-class standard. The opinion of the Van Gogh Museum experts, released just after the unveiling of the sketchbook, is convincing: that they are in fact ‘imitations’ containing ‘striking topographical errors’ — such as omitting part of the asylum at Saint-Rémy — which Van Gogh did not otherwise make. The verdict is also a relief. If the sketchbook had proved genuine it would have contained a truly shocking revelation: that Vincent could be this bad.

Comments