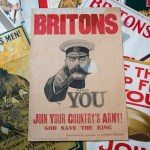

Tapestry of war

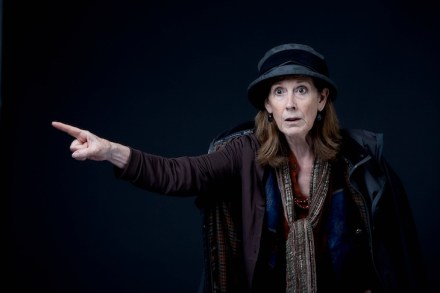

It feels like a long time since the launch of Home Front on Radio 4 back in June 2014, retracing day-by-day events of 100 years ago as Britain went to war. It is a long time. Yet still the violence in Europe rages on while back home the families of the men and boys in trenches carry on as normal, putting on plays at the local theatre, selling toys, running art classes, working the trams. A new season (number 13, with two more to go before the series ends on 9 November) starts up again on Monday. It may be an everyday story, says its editor, Jessica Dromgoole, but it’s