Contours of the mind

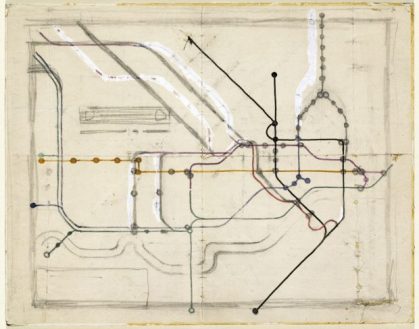

In Australia, I have been told, the female pubic area is sometimes known as a ‘mapatasi’ because its triangular shape resembles a map of Tasmania. And since we are discussing cartography and the nether regions, it is wonderful to find in the British Library’s new exhibition, Maps and the 20th Century, that Countess Mountbatten wore knickers made out of second world war airmen’s silk escape maps. Maps certainly colonise our imaginations in many different ways. The allies in Iraq had a ‘road map’ rather than a strategy. So much of personal value can be lost in the creases and folds of our own ‘mental maps’. And couples who often travel