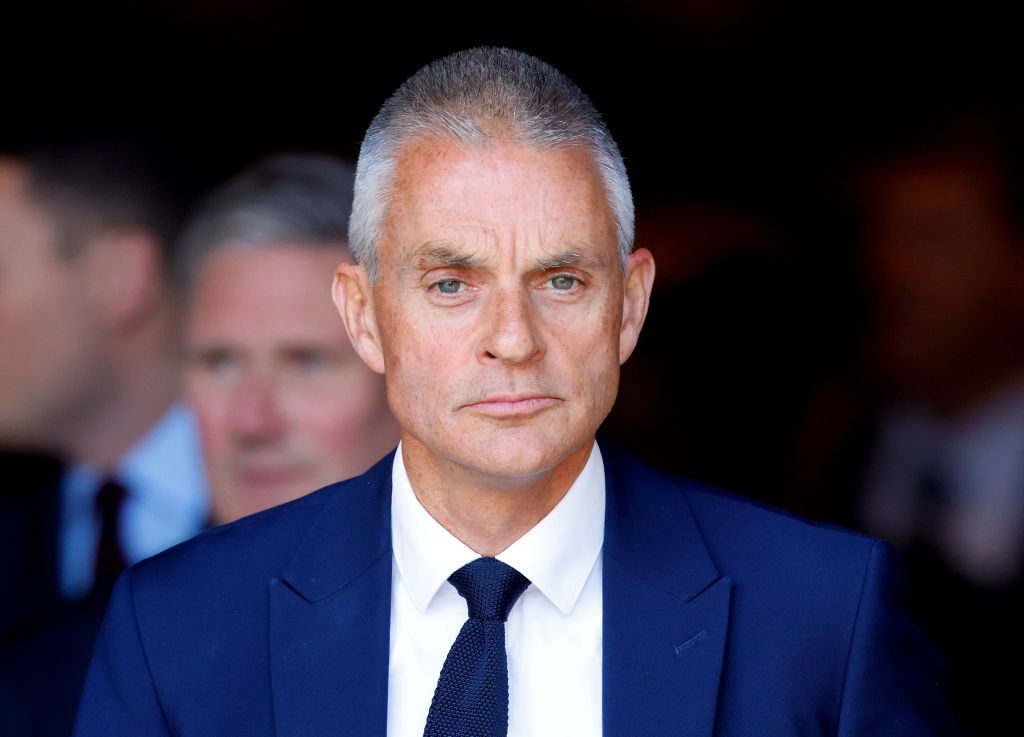

John Savournin has been busy. That comes with the territory for a classical singer – things often get a little hectic as the music world barrels towards Christmas. But with Savournin, it’s sometimes hard to keep track of which theatre – which city – he’s in on any given night. ‘This week has been Pirates of Penzance rehearsals at English National Opera,’ he says: we’re a fortnight away from opening night, and he’s playing the Pirate King. ‘On Thursday I was bobbing up to the Lowry in Salford for Ruddigore with Opera North.’ He’s been swirling his cape as Sir Despard Murgatroyd since late October. ‘And yeah – whenever I can, I’ve been checking in on panto rehearsals.’

At Opera Holland Park, Savournin brought the house down without singing a note

And that’s the difference, right there. True, Savournin is a bass-baritone in demand; the indispensable man whenever (and it’s increasingly often) a major company is looking to cast a Gilbert & Sullivan revival – though roles by Britten, Richard Strauss and Thomas Adès also feature in his repertoire. He’s a comic actor of irrepressible, instinctive charisma; the kind of performer who can get a laugh with the lift of an eyebrow. At Opera Holland Park this summer, he practically stole the show as the butler Sante in Wolf-Ferrari’s Il Segreto di Susanna – no small feat, because Sante is a silent role. Savournin brought the house down without singing a note.

But he’s also a director, artistic director, in fact, of an opera company that doesn’t think twice about creating its own annual pantomime and taking it straight into the West End. Savournin is artistic director of Charles Court Opera, purveyors of deliriously inventive small-scale comic opera from G&S to Rossini. Together with CCO’s musical director David Eaton, Savournin founded the company in 2005 while he was still a student at Trinity Laban. In February 2025 CCO celebrates its 20th anniversary with The Magic Flute. But first, yes, there’s panto; a panto staged by an opera company with a track record of making mischief.

‘It started when we were cutting our teeth in G&S back at the Rosemary Branch in Shoreditch – a very sweet 60-seat pub theatre,’ explains Savournin. ‘I’d mentioned to David that I was really interested in doing a Christmas pantomime because I’d grown up with amateur dramatics in Sheffield. We picked Cinderella because it felt like an obvious place to start, but as time went on, we thought it would be interesting to find titles that subvert the genre a little.’

He’s not joking. Previous CCO pantos have included Beowulf and the Odyssey – dizzy, gag-a-minute collisions of pop culture, opera, flatulent horses and the occasional ancient Greek joke, detonated like a musical party-popper in the tiny Jermyn Street Theatre. This year’s show – written by Savournin and Eaton – is titled Napoleon: Un Petit Pantomime. Ever the showman, Savournin won’t give too much away, though he does promise ‘a little bit of classical’ amid the anarchy.

‘This year has been slightly different – I have a co-director, Benji Sperring, because I’m down the road waving my sword around at ENO. But we’ve found ourselves with something that feels quite off-piste – somewhere between Monty Python and The Mighty Boosh. Some of our company are musical theatre-based, some can turn their hands to popular music, and of course some are opera singers first and foremost. There’s something about that that’s very pleasing – that the musical values are as important as the theatricality.’

Those values are important to Savournin. On stage, he’s larger than life: no one right now swashes a buckle or twirls a moustache with more madcap panache. Off stage, you wouldn’t necessarily pick him out from a crowd. All that creative energy is focused outwards, on the audience and the show. Colleagues talk about how seriously he takes his work; and the business of building and sustaining an opera company without regular public subsidy in the hostile environment of 21st-century Britain presumably demands a core of – well, Sheffield steel. Savournin makes it sound eminently practical.

‘We’ve deliberately taken it reasonably slow – not running before we can walk. We’ve been fortunate with some individual sponsorship from people who love the work that we do. But mainly we rely on our audiences and the box office. And we’re really lucky that people still want to come and see what we do.’

It’s more than just luck, though. Savournin started out in an am-dram family: he played the Judge in Trial by Jury at the age of 11 and he’s never doubted that comic opera, done with imagination and verve, can command a wide public. His gift, as director and performer, is to make what we see on stage feel as fresh as Sullivan’s melodies and Gilbert’s wit. G&S took infinite pains over the business of musical comedy, and the Australian director Barrie Kosky once said that directing operetta is tougher than directing Wagner. Savournin feels the same way: ‘You’re constantly walking this tightrope. You want it to feel spontaneous and playful, but on the flip side, there are times when it has to be incredibly disciplined and rehearsed. A good route through it is to make sure that what’s happening feels completely truthful and logical to the characters. Gilbert writes really good sitcoms, in the true sense of situational comedy. If you really buy that the characters are in their situation – that it’s really happening to them and that they really care about it – then I think the comedy just blossoms.

‘But it’s a massive challenge, especially when spoken text is involved and the music is supportive of the text, which is what Sullivan does so brilliantly. His music is a silver platter on which the words are served – unlike, say, Puccini, where the score underlines what the emotion is supposed to be in an almost filmic way. It’s a challenge, but it’s absolutely deliciously rewarding when it pays off.’

Savournin’s opera company doesn’t think twice about creating its own annual panto

Incredibly – counterintuitively – it really does pay off, in every sense. Cash-strapped national opera companies are realising that comic opera can be good box office; and word has got around that Savournin knows the game from the inside out. Later this season he’ll direct Trial by Jury and The Merry Widow for Scottish Opera. Singer-directors are rare; singer-directors who manage their own company and write pantomimes too are pretty much unheard of. Multitasking is a useful skill in straitened times, but does Savournin ever feel that opera – especially in Britain – is an endangered career choice?

‘Everyone in the industry hopes that there will be an adjustment to arts funding in this country. When you look overseas at Germany, where one theatre might receive more than the entire Arts Council opera subsidy in this country, that really sets an alarm bell going. Of course there is a wonderful place for fringe musical theatre, and for companies like Charles Court Opera. Everybody needs a platform to hone their craft, and audiences want to see things done in interesting places and spaces. But this can’t be at the expense of the larger scale work, which is where it all stems from. Fundamentally, it’s a massive part of our national heritage.

‘The positive thing is that the big companies are working incredibly hard to reframe how they’re presenting their work – and they have an audience that is clearly very, very happy to be there.

‘I feel really fortunate that the opera world is letting me play in both playgrounds at the moment, because I’m able to learn from directors as a singer in a very first-hand way, and I’m able to carry my own experiences as a singer into the way that I work with a cast. So yes, I’m having a good time. Despite what some might have us believe, the art form is very far from dead.’

ENO’s The Pirates of Penzance is at the London Coliseum until 21 February 2025. Charles Court Opera’s Napoleon: Un Petit Pantomime is at Jermyn Street Theatre until 5 January 2025 and its Magic Flute is at Wilton’s Music Hall from 25 February until 18 March 2025.

Comments