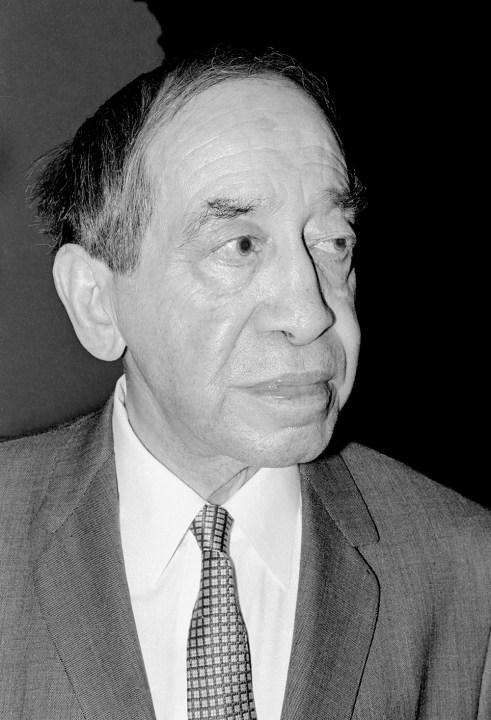

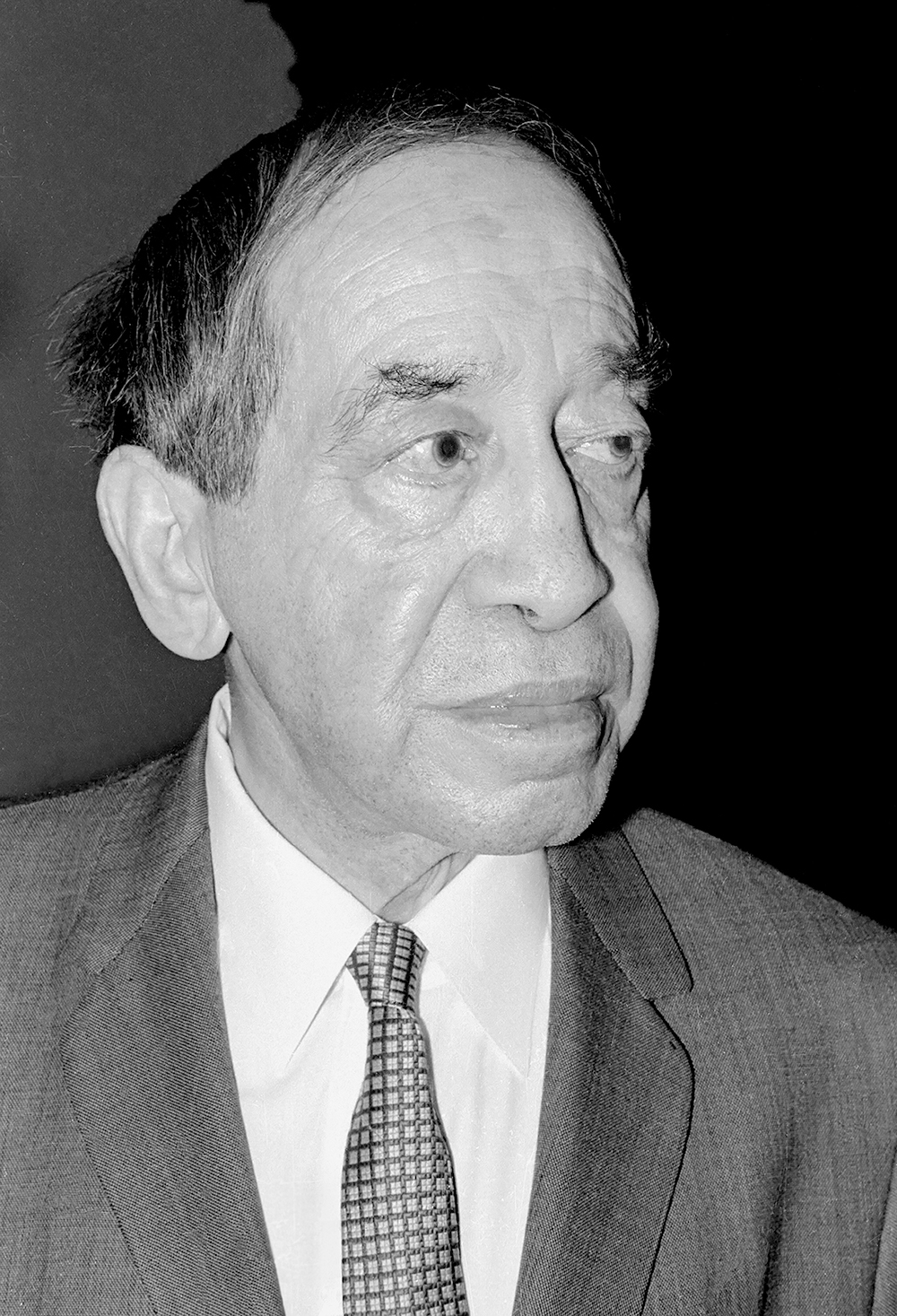

Siegfried Kracauer (1889-1966) made his name as a film theorist. His critical writings have long been available in English, and now his fiction is finally getting its due. The first of his two novels – published in Germany in 1928, five years before Kracauer fled the rise of Nazism – uses as its title his journalistic pseudonym. The protagonist inherits other autobiographical details, too, starting from the opening sentence: ‘When the war broke out, Ginster, a young man of 25, found himself in the provincial capital of M.’

Germany’s descent into the Great War is sketched in vividly cubist images. One character ‘consisted of three spheres stacked on top of one another to form the outline of a bowling pin’; another’s ‘figure possessed the amiability of a rectangle’. The military are reduced to empty shells: ‘The dress uniform in the silver train’ next to ‘a double-breasted tunic.’ There is no shortage of metal; even ‘workers… looked like spare change, with mustaches, heavy and made of nickel’.

An architect, Ginster dreams of designing ‘a large kaleidoscope in the ceiling over the pool that will be set in motion with a mechanism and constantly project shifting shapes in ravishing colours’. What’s required instead are cemeteries for soldiers and factories producing army supplies. Following Ginster’s pencil as it traces ‘paths [running] in obedience to strict rules’ and ‘trees clipped into cubes’, the translator Carl Skoggard executes these drawings with a similar precision.

Ginster is unfit for military service, but his friend Otto has enlisted. Their meeting is awkward: ‘They’ve forced him into a perfect rectangle, thought Ginster, an automaton.’ Others have also changed, for ‘ever since war was declared, no one talked any longer about important things’. Many believe it’ll be over soon, and that life must go on. When Ginster learns of Otto’s death on the front line, he is doubly ashamed: of feeling happy to be alive and of hating ‘the emotions, the patriotism, the huzzahs, the banners’. But the ‘empty space’ left by Otto is soon ‘sealing itself up’, and life goes on, filled with work and romance. When Ginster is eventually conscripted, he starves himself to ‘general physical debility’ and is sent ‘to peel potatoes against the foe’.

Ginster has been compared to Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front and other contemporary novels exposing the insanity of war. Kracauer does it in his own way, treating modernity itself, with its ‘spoiled’ machines and ‘perfectly angular’ lines, as a blueprint for catastrophe. Having survived it, his unheroic hero can only weep ‘for himself, for countries and human beings’.

Comments